The Man Who Set Out to Kill Segregation… or Be Killed by It

Charles Person Remembers Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth and the Movement in Birmingham

Anyone who spent time in the Movement knew the name Fred Shuttlesworth. Reverend Shuttlesworth committed his life to fighting injustice in Birmingham, where segregation was more than idea and policy. Segregation stood tall and fixed. Inflexible as steel. Immovable as a mountain. Birmingham was the most segregated city in America, the toughest bastion of racism in the United States. Whites called it the Magic City; blacks called it Bombingham.

Reverend Shuttlesworth was crazy bold because he intended to “kill segregation or be killed by it.” And he was willing to face Goliath alone. He announced civil rights actions he intended to take in advance, and then he took them. Consequences be damned.

In 1956, the week the Montgomery Bus Protest ended in victory, Fred Shuttlesworth announced he would lead Birmingham’s Negro citizens onto city buses the day after Christmas. It was the direct opposite of Montgomery. Instead of boycotting buses, Reverend Shuttlesworth would flood them with black passengers. They would sit in any seat they chose. Shuttlesworth was saying, “Here we come.”

Christmas night—twelve hours before execution of the plan—Reverend Shuttlesworth’s home blew up with him in it. Sixteen sticks of dynamite blasted the parsonage into oblivion. Neighbors rushed from their houses to see their pastor’s home in ruins. Police approached the crater. So did members of the Klan. Parishioners gathered to mourn their minister’s death. Police and Klan to celebrate it.

Anyone who spent time in the Movement knew the name Fred Shuttlesworth.Out of the rubble climbed Fred Shuttlesworth in pajamas. Untouched. Unscathed. To Reverend Shuttlesworth, it was God’s hand on his life. Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego survived the fiery furnace of Nebuchadnezzar. Daniel survived the lion’s den. Now, God was saving Reverend Shuttlesworth from Bombingham’s dynamite. He approached a policeman he knew to be a member of the Klan. The policeman spoke first.

“I did not think they would go this far, Reverend. I’ll tell you what I’d do if I were you. I’d get out of town as quick as I could.”

“Officer, you’re not me. Go back and tell your Klan brothers that if the Lord could save me through this, I am here for the duration. The war is just beginning.”

Nine months later—September 1957, the same month the Little Rock Nine captured the front pages of America’s newspapers—Reverend Shuttlesworth announced, a week before the start of school, that he would enroll his daughters in a white school. Within days, a carload of Klansmen accosted a young black couple walking a local country road. They pistol-whipped the man. They told him to relay a message: “Stop sending nigger children and white children to school together . . . or we gonna do them like we’re gonna do you.” They stripped the man naked and castrated him with a razor blade.

Only one man in Birmingham was planning to integrate city schools. Fred Shuttlesworth. This act of profound violence was a telegraphed message to the only man I can think of who would be undeterred and uncowed by such threat against him or his family.

What would I have done in that horrific circumstance? Not what Fred Shuttlesworth did. The first day of school, Reverend Shuttlesworth walked his daughters, Ricky and Pat, toward the all-White school. A mob surrounded them.

“We’ve got this son of a bitch. . . . Let’s kill him.”

The mob pounded Reverend Shuttlesworth and beat him and chained-whipped him and pummeled him and tried to kill him. He just did not die.

Now, the Freedom Ride was in Fred Shuttlesworth’s city. The need was great, and a great man was available to answer the need.

The door closed. The bus lurched forward. I held on to a pole and steadied myself. Eyes stared at me. I ignored them. I stayed standing where I was. I had started the day at the front of a Trailways bus. I wanted to end the day at the front of a bus. The White driver looked ahead and drove. I don’t know how long. The bus slowed to a stop. I had no idea where we were. He opened the door and looked at me almost with compassion.

Out of the rubble climbed Fred Shuttlesworth in pajamas. Untouched. Unscathed.“I’ll let you off here. Head across those tracks.” His voice had empathy. He wasn’t ordering me off or telling me where I should “git” to. He was offering me something. A sense of direction. Like a compass.

“Thanks,” I said, returning his gentleness with a tone of gratitude. I stepped off.

It was such a brief exchange. He didn’t charge me anything. He didn’t snarl or bully or mutter indignantly. He was kind. It was so different from what I had experienced all day—the nicest thing that had happened to me since entering the state of Alabama.

As a child, I reveled in choo-choo trains, huffing and puffing and billowing thick black smoke. Kenneth and I would sit down as close as we could to the rumbling iron so we could feel the ground shake as trains passed. We loved the smell of burning coal and the sight of something so big and powerful.

My parents commanded us not to cross the tracks. It was too dangerous. We thought they wanted to keep us safe from the train cars. And they did. But as I grew, I came to understand “Don’t cross the tracks” was a different instruction from “Don’t play on the tracks” or “Don’t walk on the tracks.” I came to understand Mom and Dad were protecting Kenneth and me from what was on the far side of the tracks.

That’s what the driver was doing. Taking me to the tracks. Protecting me. He and I both knew the other side of the tracks meant the Black section of town—“my” section of town—where people like me would take care of people like me. In other words, the poor section, the area of urban blight that my social studies book at David T. had taught me about. In Atlanta, I lived on “the other side of the tracks.” He was dropping me off in the same relative place in Birmingham. In his kindness to me, he was saying all I had to do was cross them and I would be okay. I’d be safe.

I crossed the tracks and spotted a phone booth. All of us on the Ride were required to carry pocket change, so we could place phone calls if needed. This was my day to need the change. I picked up the receiver and inserted a coin. The voice on the other end was Fred Shuttlesworth.

“What do I do?” I said. My thoughts fuzzy, my surroundings unfamiliar. I had just escaped and was in a strange city. Now what? It was a question familiar to Fred Shuttlesworth.

“Where are you?”

“I don’t know. The tracks.”

That could have been anywhere. Birmingham’s industry guaranteed railroad tracks. My memory of this is in pieces, but I must have given enough landmarks.

“Stay there. Help’s coming.”

Birmingham was Fred Shuttlesworth’s city. He knew how to find people in trouble.

I felt light-headed. Unsteady. I sat down on the tracks. And waited. Cars passed. None slowed. My head felt wet. I didn’t care. I cared about a car stopping.

One did. Who knows how long it took? Two men got out. The driver didn’t. They introduced themselves. I don’t remember their names. Deacons from Reverend Shuttlesworth’s church, they said. They checked me over and looked alarmed. The top of my head, they told me, had a gash. That’s why my fingers were wet. I don’t remember reaching up to feel it.

“You need to see a doctor.”

We drove off. Time disappears when you’re in shock. Feeling wet doesn’t matter. You think of minor stuff and ignore the major.

“Where’s my coat? What happened to my coat?”

That’s what you think. The blood doesn’t matter, but who the hell took my coat?

They gave me a towel and told me to press it against my head. We pulled into a driveway. The men told me to stay put. I don’t know how long I waited. They came back and started the car.

“What was that about?”

“He’s not going to see you. We’re moving on to the next one.”

Two more stops. Two more “moving on.”

There were three black doctors in Birmingham, I found out that day. All were afraid to treat me. The doctors saw us as “outside agitators.” Birmingham’s segregationist propaganda had seeped into the black community. That’s the depth of fear Birmingham fostered. Members of my own community saw me as trouble. For them.

Thugs on a bus. A mob attack. Now, Negro doctors refusing to treat me, a Negro patient. This day told me in Birmingham there lived a different brand of segregationist. The whites of this city saw war coming to their community, saw me as an invader. They were prepared to defend their city. Or at least their lifestyle, their customs, and their prejudices. They were prepared to defend them with deadly force. The blacks lived in tangible fear of the consequences of getting “out of line” with white standards.

__________________________________

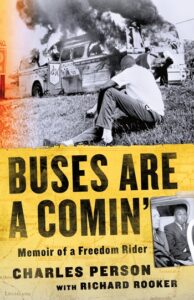

From Buses Are a Comin’ by Charles Person. Copyright © 2021 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.