Sady Doyle on the Man Who Insisted His Wife Was a Malevolent Fairy

When the Only Explanation for a Powerful Woman is Dark Magic

What does one tell a husband? One tells him nothing.

–Cat People (1942)

*

One Friday night, in March 1895, Michael Cleary of Ballyvadlea, Ireland, set fire to his wife for refusing to eat a piece of toast.

Bridget Cleary had always been a bad fit for Michael. She was an exceptionally beautiful woman, and—thanks to her parents’ purchase of a Singer sewing machine—an exceptionally powerful one, too. Bridget taught herself to work as a milliner and dressmaker, which, along with keeping poultry, allowed her to live off her own income. That level of independence was rare in a married woman, and Bridget didn’t do much to downplay it: She had not moved in with her husband for some time after their wedding. She wore ostentatiously stylish clothes of her own design, in part as a walking advertisement for her business, but also for all the reasons beautiful women wear stylish clothing. She had a reputation for arrogance; “people speak of [Bridget] as being ‘a bit queer’ in her ways,” one local newspaper wrote, “and this they attribute to a certain superiority over the people with whom she came into contact.” There were rumors that she’d been having an affair.

“She was not my wife. She was too fine to be my wife,” Michael said of Bridget after her death. It might sound like bitterness, a man venting his insecurity at a woman who made him feel small. But Michael was being literal. He also claimed the woman he’d killed was “two inches taller than my wife.” By the time he was on trial for murder, Michael was not framing the problem in terms of some flaw in Bridget. He claimed that the woman he’d killed was not Bridget at all.

The thing that looked like Bridget, Michael said, was a changeling.

The thing that looked like Bridget, Michael said, was a changeling—a fairy that assumed someone’s appearance in order to disguise the kidnapping of the original person. Though they preferred to take children, fairies also stole adult women from time to time, especially pretty ones or nursing mothers. Like the vampires of New England, the changelings of Ballyvadlea were surprisingly noncontroversial. When Michael asked Bridget’s family to drive the changeling away, they were glad to help.

In the days leading up to her death, Michael’s neighbors recalled hearing screaming coming from his house—“take it, you [bitch], you old faggot, or we will burn you” was one widely reported comment—and seeing Bridget tied to the bed, where she was doused and force-fed potions to repel fairy magic. Sometimes that meant herbs boiled in milk. Sometimes it meant urine. Fairies hated iron, so she was threatened and prodded with a hot poker; fairies hated Christianity, so a priest was called. Bridget was made to recite her name and her male relatives’ names; she had to describe herself as “Bridget Boland, wife of Michael Cleary, in the name of God” over and over, as if the spell could be broken by reaffirming the proper marital relation. When she was slow to answer, they held her over the kitchen fire. Johanna Burke, Bridget’s cousin, affirmed in her testimony that Bridget “seemed to be wild and deranged, especially while they were so treating her.”

Here’s the thing: it worked. After hours of counter-magic, everyone agreed that the real Bridget had been returned to them. But then, while the participants were recuperating by the fire, Bridget made the mistake that would end her life. She insulted Michael’s mother.

“Your mother used to go with the fairies,” is what she said, according to Johanna. “That is why you think I am going with them.”

The toast was on the breakfast table. Bridget had eaten two pieces. When she refused a third piece, Michael knocked Bridget to the ground and began forcing the bread down her throat. He began demanding that she call herself “the wife of Michael Cleary” again.

“I said, ‘Mike, let her alone, don’t you see it is Bridget that is in it,’” Johanna said, “meaning that it was Bridget his wife, and not the fairy, for he suspected that it was a fairy and not his wife that was there. Michael then stripped his wife’s clothes off, except her chemise, and got a lighting stick out of the fire. She was lying on the floor, and he held it near her mouth.”

Michael held fire to his wife’s mouth, telling her to take back what she’d said.

Fairies hated fire. So Michael held fire to his wife’s mouth, telling her to take back what she’d said. Some of the witnesses remembered her crying out for Johanna—“oh, Han, Han”—and Johanna remembered Bridget saying, “give me a chance,” but then her head hit the floor, hard, and she stopped talking. So it may have been the blow to the head that killed her. We can’t know. Somehow, in the struggle, a spark got loose, and Bridget’s chemise caught fire. Over the screaming of her assembled family, Michael reached for a lamp and poured the burning oil over Bridget’s body, stoking the flames.

James Kennedy, her aunt’s brother-in-law, recalled trying to stop him: “For the love of God, don’t burn your wife,” he shouted.

“She’s not my wife,” Michael said. “She’s an old deceiver sent in place of my wife. She’s after deceiving me for the last seven or eight days, and deceived the priest today too, but she won’t deceive anyone any more. . . . You’ll soon see her go up the chimney!”

They assembled family, believers all, may well have looked for the miracle. But the body of Bridget Cleary stayed where it was.

*

It’s difficult to tell what motivated Michael in those final moments. It wasn’t just his belief in fairies; the other participants believed in them, too, but by the time Michael killed Bridget, everyone else knew that she was a real person. It may have been that Michael believed in fairies a little more than the others. It may have been mental illness; one popular theory places the blame on Capgras syndromes, in which sufferers are afflicted with the delusion that a loved one (“usually a spouse,” as per one Irish doctor) has been replaced by an identical duplicate. Or, given what we know about the other men, the obvious pride Bridget took in herself, and the financial power she wielded—say it plainly: the fact that Bridget was not under her husband’s control—it may have been a lie, and a way to justify killing her. Men kill women every day to assert their authority. Bridget wouldn’t have been the first.

But if Michael was lying, it was a lie with deep roots. Ireland and the other Celtic countries have a long folkloric tradition of fairy wives. Like Bridget, they were women who were hard to keep in one place—women who asked for more than was normal.

In the typical story, as per W. Y. Evans-Wentz, “a man catches a fairy woman and marries her. She proves to be an excellent housewife, but usually she has had put into the marriage-contract certain conditions which, if broken, inevitably release her from the union, and when so released she hurries away instantly, never to return, unless it be now and then to visit her children.”

Men kill women every day to assert their authority. Bridget wouldn’t have been the first.

Among the conditions, ironically, is the right to leave an abusive husband; in one story, collected by Evans-Wentz, the man learns “that he must not strike the wife without a cause three times, the striking being interpreted to include any slight tapping, say, on the shoulder.” Other fairies are disquietingly independent; a selkie, for instance, will come into her new husband’s home with a trunk, which he is not to open under any circumstances. If he disobeys her—suspecting treasure, or just not wanting her to have any secrets—he will find that the trunk contains only a sealskin, which the selkie will use to transform herself back into a seal before disappearing into the sea. In the Welsh Mabinogion, we have the story of Rhiannon, a fairy woman pursued by the human Prince Pwyll, who was struck by her beauty as she rode through his kingdom. Pwyll chased Rhiannon for days, unsuccessfully, until he became so tired and hungry that he begged her to stop. Only then did Rhiannon turn around: “I will stay gladly,” she told him, “and it were better for thy horse hadst thou asked it long since.” Rhiannon had been in love with Pwyll from afar, and had come to propose marriage, but she wasn’t going to let him grab her off the road and call it conquest. To be with a fairy woman, even one who loved him, a man had to get her consent first.

The ur-myth here is probably the French story of Melusine. When she married Count Raymond of Poitou, her only demand was that he leave her alone in her own room on Saturdays. Raymond agreed, and for many years, they were almost happy. Yet each of their children was born strange and frightening—with claws or tusks, or too many eyes, or too few. Though the maladies varied, “all were in some way disfigured and monstrous.” The problem defied explanation, and in time, Raymond grew suspicious of his wife. One Saturday, he peeked through a crack in the door and saw Melusine, taking a bath, with the lower half of her body transformed into a long, snaky tail.

Melusine loved Raymond, and initially forgave him for spying on her. It was only when Raymond publicly called her a “serpent” and blamed her for “contaminating” his noble line that she dropped the act, transformed into a sea dragon, and flew away. The legend says that she came back in the dead of night to nurse and hold her children, proud Mama Snake cuddling her little monsters to her clammy breast. Melusine could forgive her husband for curiosity, or even for being afraid, but not for turning on their children; she may have been a hideous, recently divorced hell-snake, but she was not a bad mother.

“Fairy wives” behaved less like inexplicable creatures of the spirit world and more like women who’d figured out how to have long-term heterosexual relationships without ceding their dignity or autonomy. So if Michael Cleary had a wife who was more beautiful than ordinary women, who wielded more control than ordinary women, who acted “too fine” for him or anyone, who had a habit of disappearing—well, he knew what to call her. If tradition had taught him anything, it was that a woman who insisted too much on being treated like a person was probably not a person at all.

————————————————————

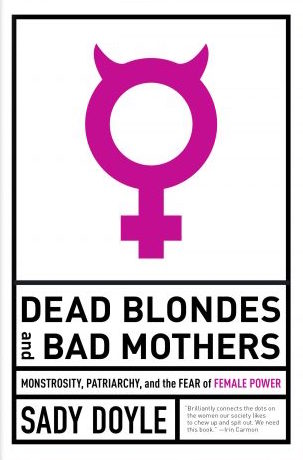

From Dead Blondes and Bad Mothers: Monstrocity, Patriarchy, and the Fear of Female Power by Sady Doyle. Published with permission of the publisher, Melville House Books. Copyright © 2019 by Sady Doyle.

Sady Doyle

Sady Doyle is the author of Trainwreck: The Women We Love to Hate, Mock, and Fear . . . and Why. Her work has appeared in In These Times, The Guardian, Elle.com, The Atlantic, Slate, Buzzfeed, and Rookie, among other publications. She is the founder of the blog "Tiger Beatdown," and won the first-ever Women’s Media Center Social Media Award. She’s been featured in Rookie: Yearbook One and Yearbook Two, and contributed to the Book of Jezebel. She is the author of Dead Blondes and Bad Mothers (Melville House, 2019).