In the days of conductors, of course, such matters could be dealt with speedily. A conductor like Gunter, for instance, would locate the offender and tell them in no uncertain terms to leave the bell alone. If they obeyed, all well and good; if they didn’t, he ordered them off the bus. Nowadays we had driver-only operation and it was not so straightforward. Every time the bell rang we had to assume it was ‘genuine’ and pull up at the next bus stop. If nobody got off there was nothing we could do except close the doors and continue our journey. This was a regular occurrence. It even happened to Jason.

‘They never own up to it,’ he announced after one such incident. ‘You could march round the bus threatening the lot of them with a horsewhip, but they would never confess to ringing the bell.’

I liked to think he meant this in a hypothetical way, but you couldn’t always be sure with Jason. All the same, he had his own solution to the problem:

‘If they keep doing it on my bus I give them some treatment with the brake and the accelerator,’ he said. ‘Rough them up a bit: teach them a lesson.’

‘What about all the innocent people?’ I asked. ‘The ones who haven’t touched the bell?’

‘Tough, isn’t it?’ said Jason.

It was mid-morning. We were parked up at the cross, standing by our buses and drinking tea from paper cups. Jason was in his usual belligerent mood. ‘Guess what this cunt said to me just now?’

‘Which cunt?’ I enquired.

‘This fireman.’

‘Don’t know.’

‘He said I was driving too fast.’

‘Blimey.’

‘Fucking cheek!’

‘I’ll say.’

‘He told me I should only be going at walking speed.’

‘Was he in his fire engine?’

‘No,’ said Jason. ‘He was up a ladder.’

‘Good morning, gentlemen,’ said a voice beside us. We had been joined, uninvited, by Woodhouse.

‘Morning,’ I replied.

Jason said nothing, and stood glaring with astonishment at the man who had dared to interrupt our discourse. Woodhouse was looking very relaxed in a pale linen suit and flowery tie. He, too, was holding a drink in a paper cup: some sort of fancy coffee with a lid on.

‘How’s our ridership today?’ he asked.

‘Pardon?’ I said.

‘Our passenger profile,’ said Woodhouse. ‘Is it in a positive trend?’

‘Not sure really.’

‘If there’s a downturn we’ll need to redefine our targets.’

‘Yeah.’

‘Or at least revise our threshold,’ he added. ‘Given that seat occupancy never fully represents total capacity.’

This was all too much for Jason. ‘Look, mate,’ he said. ‘What the fuck are you talking about?’

It dawned on me that Jason had no idea Woodhouse was part of the senior management ‘team’. Or maybe he did know, and didn’t care. Which was fair enough.

Admittedly, Jason could be churlish at times, but Woodhouse was equally at fault for simply butting in on our conversation. The situation threatened to turn unpleasant at any moment. Woodhouse, however, was a master of diplomacy.

‘I’m so sorry,’ he said, thrusting his hand out. ‘Jeremy Woodhouse. Customer approval consultant.’

Reluctantly, Jason took the proffered hand and shook it.

‘Jason Reilly,’ he murmured. ‘Mass transportation operative.’

‘I was referring to bus loadings,’ Woodhouse explained. ‘The ratio between passenger numbers and journeys completed.’

‘Oh those,’ replied Jason. ‘You should have said.’ He examined the remains of his tea with disgust before pouring them into the gutter.

‘I see you’ve been testing a new vehicle,’ I remarked. ‘Should carry a lot more people.’

‘The articulated bus?’ said Woodhouse. ‘Yes, the trials have been a great success: the engineers’ report was full of praise. We’re planning to introduce a pilot service along the ring road.’

‘Seems like a good place to start.’

‘The possibilities are huge, of course, when you consider there are three main-line railway stations standing side-by-side in all their Gothic glory. We’re hoping to move a million passengers every day. Even more once we’ve completed work on the sea tunnel.’

‘They’re not all Gothic,’ said Jason. ‘Only the one in the middle.’

‘Really?’ said Woodhouse.

‘The other two are purely utilitarian. It’s more like Cinderella and her ugly sisters.’

‘Well, I must remember to bear that in mind,’ uttered Woodhouse with a furrowed brow. ‘Maybe I need to alter my presentation.’

He took a notebook from his pocket and wrote something down.

‘I expect these new buses are expensive,’ I said.

‘Astronomical,’ said Woodhouse.

‘Funded by the taxpayer?’

‘Naturally.’

‘Who’s going to drive them?’

‘Good question,’ said Woodhouse. ‘They’ll certainly require drivers of advanced experience. The articulated body could be rather daunting to some, I imagine, not to mention the increased brake horsepower. The acceleration is quite phenomenal apparently.’

‘Oh yes?’ said Jason.

‘Therefore, the driver selection process will need to be rigorous.’

‘Suppose so.’

‘Each garage will put forward suitable candidates based on their length of service, their safety record and so forth.’

‘Is there a waiting list?’ I enquired.

‘Well, it’s still early days yet,’ said Woodhouse.

‘Are you interested then?’

‘Not really,’ I said. ‘I’m a strictly double-decker man.’

He turned to Jason. ‘How about you?’

‘I’ll think about it,’ came the reply.

‘Well, gentlemen,’ said Woodhouse, glancing at his wristwatch, ‘I really must dash. Nothing but meetings, meetings, meetings for me, I’m afraid. Good to talk to you both. Bye.’

‘Bye,’ we each said, and then he was gone.

I grinned at Jason. ‘That was impressive,’ I said. ‘I didn’t know you knew about architecture.’

‘I don’t,’ said Jason. ‘Neither does that cunt.’

* * * *

A small but regrettable incident had taken place during my northbound journey. The road works involving the burst water mains were still underway and they had begun to encroach on a bus stop situated nearby. Accordingly, the stop had been put out of commission and a temporary ‘dolly’ stop set up about a hundred yards further along the road. The out-of-use bus stop was clearly marked with a yellow hood bearing the words not in use. Nonetheless, when I approached from the south I saw a group of around a dozen people waiting there. Another group of a similar size was standing by the dolly stop.

Now, the purpose of this closure was two-fold. Firstly, it was to prevent people at the bus stop from getting splashed with mud from the nearby excavations. Secondly, it was to reduce the congestion which would inevitably be caused by a bus halting in the middle of the road works. Needless to say, the people at the out-of-use stop were oblivious to either of these reasons. It was the height of the early rush and most of them were in their usual dazed state. Paying attention to notices at this time of the morning was seemingly beyond them as they stood in a huddle waiting for the bus. One or two vaguely put their hands out as I drew near. The rest did nothing at all. Meanwhile, the people at the dolly stop were frantically waving their arms in a frenzied attempt to attract my attention. These were the ‘righteous’ people. They knew propriety was on their side, but they could not be certain whether justice would be done.

Slowing down to negotiate the road works I noticed that the people at the out-of-use stop were gathering into a tight knot as they prepared to board. At the last moment a couple of them raised their hands slightly like discreet bidders at an auction. Then, when I drove straight past, they gazed at the bus with incomprehension. Half a minute later I reached the dolly stop, where the righteous people were congratulating one another on their supposed moral superiority. Without exception they came onto the bus wearing great big smiles. Even so, I didn’t really like leaving the oblivious people behind, so I waited a while at the dolly stop to see if any of them came running up. None did, and eventually I carried on without them.

The question of when and where a bus should stop was a thorny one. Apart from the abstract distinction between request and compulsory stops, there was also the matter of these so-called ‘runners’. Obviously, if a driver waited at a bus stop to allow people to catch up it was widely considered to be a good deed. Sometimes the people even said ‘thank you’. It was also a useful ploy if the bus happened to be excessively early and the driver was looking for an excuse to pause somewhere.

Confusion arose, however, when prospective passengers attempted to ‘race’ a moving bus to an empty bus stop. There was nothing more irritating to a bus driver than to be cruising in a leisurely manner towards an apparently deserted stop, only for one of these ‘runners’ to come into view, galloping along as though their life depended on it.

Runners were divided into two sub-categories: ‘logical’ and ‘illogical’. Logical runners ran in the same direction as the bus they were pursuing. Illogical runners were the ones who had given up waiting for the bus and begun walking towards the next stop. Then, when they suddenly heard the bus approaching, they came running back. It made no sense whatsoever to run away from their final destination, yet many people did this quite regularly.

In both cases the physical definition of a bus stop was crucial. It usually consisted of an upright pole with a sign attached bearing the words bus stop. This could be augmented by a large rectangle painted on the surface of the road. In some cases there would be a bus shelter: either a rustic version with a thatched roof, or a draughty urban one. In the absence of bus shelters, people were also known to gather under a nearby tree or beneath the awning of a shop. Because of all these various aspects, the precise location of any bus stop was open to interpretation. In general terms, however, it was the upright pole that seemed to count for most. ‘Runners’ always assumed that if they got to the pole first, and touched it, then the bus would be obliged to stop. (This was known in bus parlance as ‘the race for the pole’.)

Unfortunately it was not quite so simple: in reality there were many complex issues at stake. Firstly, the driver would have to judge whether he or she could stop the bus smoothly without having to slam the brakes on. Sudden halts could be jarring to both

driver and passengers alike, and tended to disrupt the overall ‘flow’ of the bus. Consideration also had to be given to the opinions of the people already on board. While some of them might be sympathetic towards the runner, others certainly may not, and hence a balance needed to be struck. Another important influencing factor was the question of time: if the bus was late then stopping for runners would only help to make it even later. Clearly in these circumstances the act of leaving people behind was an unavoidable necessity. Furthermore, the driver may be aware of another bus travelling close astern which would be in a much better position to stop and pick them up. Whether it actually did or not was an entirely different matter. Finally, some drivers were disinclined to stop because they just didn’t think it was worth it. Experience told them that most runners only wished to travel a short distance before getting off again. Besides which, the gesture was seldom appreciated: people only remembered the buses that went without them, never the ones that waited.

In the era of the VPB, of course, there was plenty of scope for compromise. Drivers could slow down and allow the more athletic runners to leap aboard without bringing the bus to a complete halt. In the past, conductors could often be seen standing on their platforms offering verbal encouragement to such valiant individuals as they ran along behind. ‘Having a go’ was considered highly dangerous and officially frowned upon. Without doubt it contributed to the demise of the open platform. Nevertheless, it was a common practice for years and led to the expression ‘catching a bus’.

This itself was a misnomer: people only caught buses if the driver allowed it to happen.

Jason, it goes without saying, had very strong views on the subject. Indeed, any mention of ‘catching a bus’ tended particularly to rankle him.

‘The way people talk you’d think they were big game hunters stalking tigers through the jungle,’ he said. ‘Or out in the ocean reeling in swordfish and marlon: ‘‘Ooh, I had a struggle catching the bus this morning!’’ For fuck’s sake, it’s pathetic! There’s a fucking bus every eight minutes! What’s so challenging about that?!’

‘Maybe it seems different from where they are,’ I suggested.

‘Huh,’ said Jason.

Personally I tried to maintain a fair and measured outlook, but at times it could be difficult. After all, it was much easier to keep going than to stop and wait for runners. Sometimes a kindly act could even backfire. Once I waited a whole minute at a bus stop

for a man who was running desperately through the early morning gloom. Only when he ran straight past me and continued up the road did I realise he was a jogger. In the final analysis the question of runners was a matter for discretion. As a point of reference, the rule book stated that we were supposed to wait for all ‘intending passengers’.

Jason’s verdict was different. ‘People wait for buses,’ he said. ‘Buses don’t wait for people.’

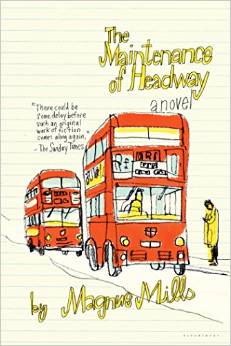

From THE MAINTENANCE OF HEADWAY. Used with the permission of Bloomsbury USA. Copyright © 2015 by Magnus Mills.