The Lost Digital Poems (and Erotica) of William H. Dickey

Matthew Kirschenbaum on Recovering Artifacts of Another Time

In 1987, William H. Dickey, a San Francisco poet who had won the prestigious Yale Younger Poets Award to launch his career and published nearly a dozen well-received books and chapbooks since, was given the responsibility of editing the 10th anniversary issue of the establishment literary journal New England Review and Breadloaf Quarterly. The theme of the issue seemed improbable at first: “The Writer and the Computer.” Yet, as Dickey remarked in his introduction, RAM and ROM were by then an inescapable part of writers’ shop talk. Personal computers had come on the market at the beginning of the decade, and authors from Amy Tan to Stephen King enthused about being able to insert and delete at will, even as others bemoaned the impersonality of the new machines—their plastic and glass facades a far cry from a well-loved typewriter or worn-down pencil.

But Dickey, who also taught creative writing at San Francisco State University, sensed there was something more at stake: the medium really was the message. “Do we think differently about what we are writing if we are writing it with a reed pen or a pen delicately whittled from the pinion of a goose, or a steel pen manufactured in exact and unalterable replication in Manchester,” he mused. “Do we feel differently, is the stance and poise of our physical relationship to our work changed, and if it is, does that change also affect the nature and forms of our ideas?”

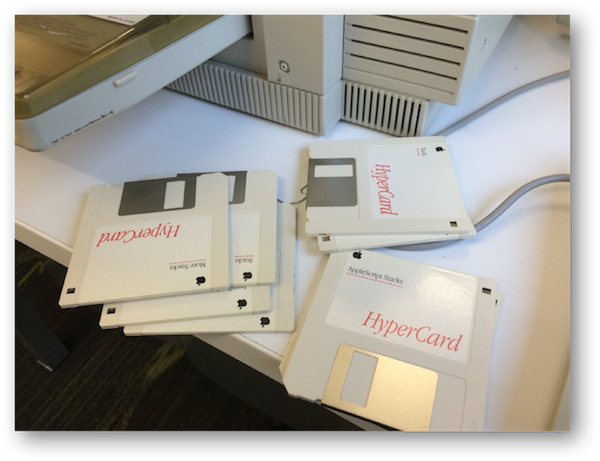

These were not idle questions for Dickey. Computers had already changed his poetry and poetics, the radiant pixels on the screen suggesting ways words could move and flow with a freedom a fountain pen could not match. A year later, he bought his first Macintosh. It came with a powerful program called HyperCard, which anticipated many of the features and behaviors that are second nature to us today on the web. With HyperCard, a user could create “stacks” of “cards” that could be linked and networked through unique patterns and pathways. Images, animations, and even sound could coexist with text on the screen, and the Mac’s full array of fonts and typography could be brought to bear.

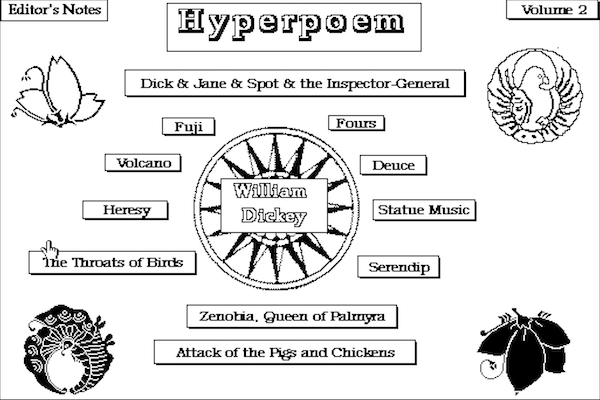

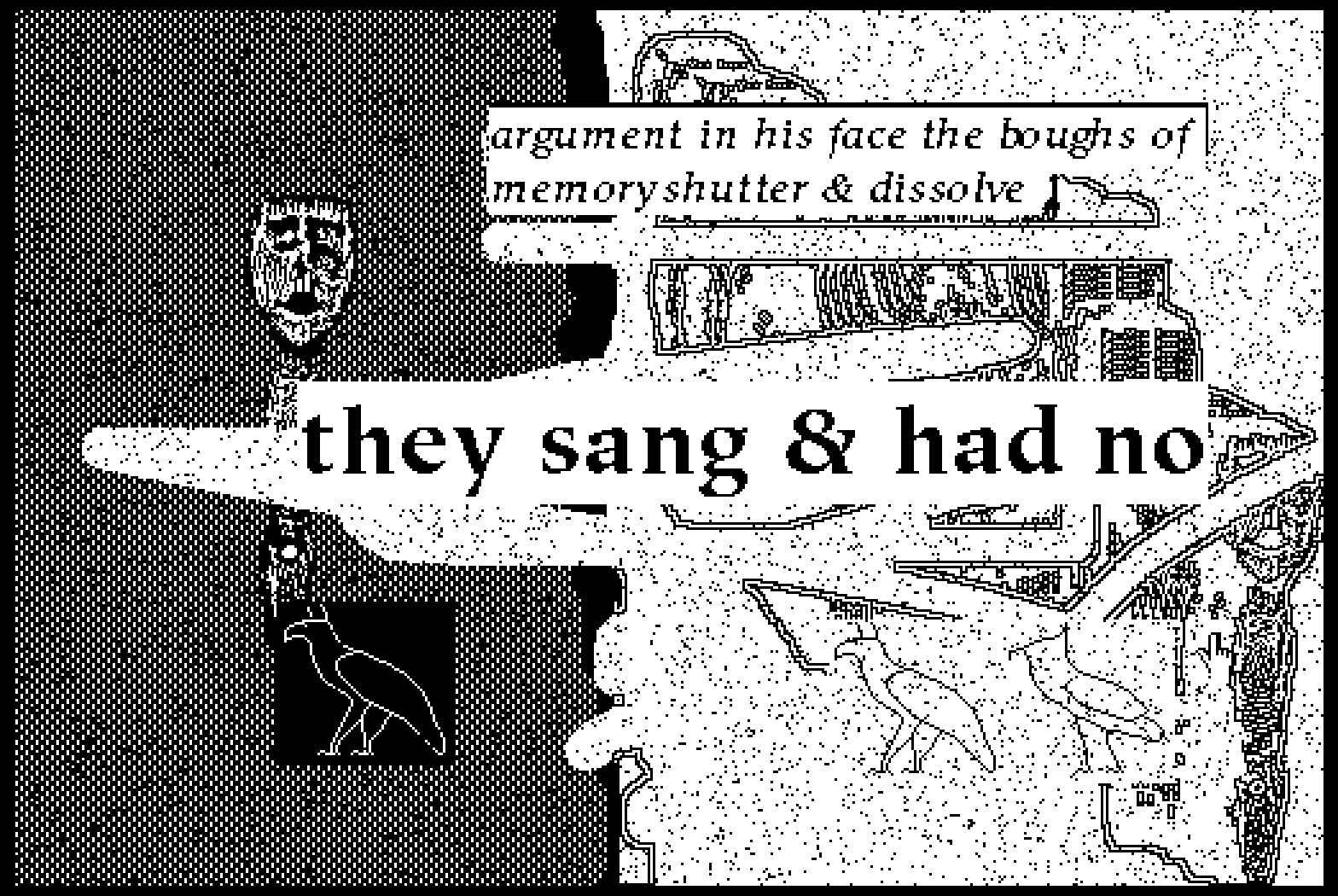

Over the next few years, William H. Dickey would use this software to produce a total of fourteen “HyperPoems” (as he dubbed them). This heretofore lost digital work addresses themes characteristic of his oeuvre—history and mythology, as well as memory, sexuality, the wasteland of the modern world, and (over and under all of it) love and death.

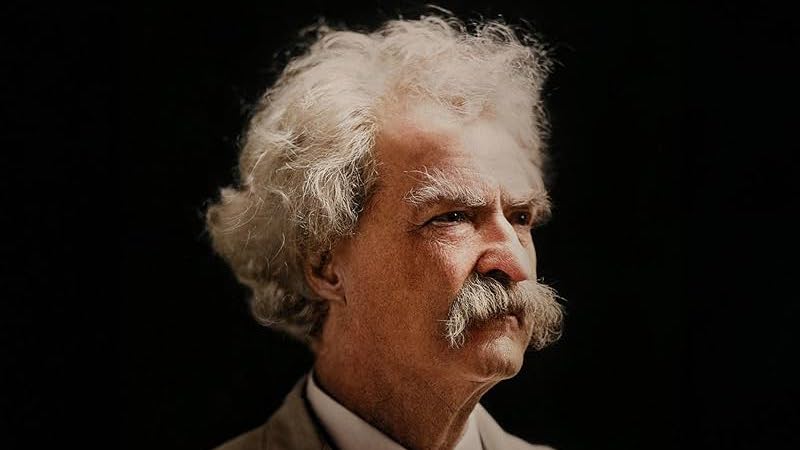

Photo via Matthew Kirschenbaum

Photo via Matthew Kirschenbaum

It was a peak creative moment, but it came in the midst of an unprecedented dark time. As a gay man living in San Francisco, Dickey found himself at the center of the AIDS epidemic. Watching helplessly as friends fell sick, he turned to the new-found freedom of the digital form to produce HyperPoems that were unique documents of gay life in San Francisco during this calamitous period.

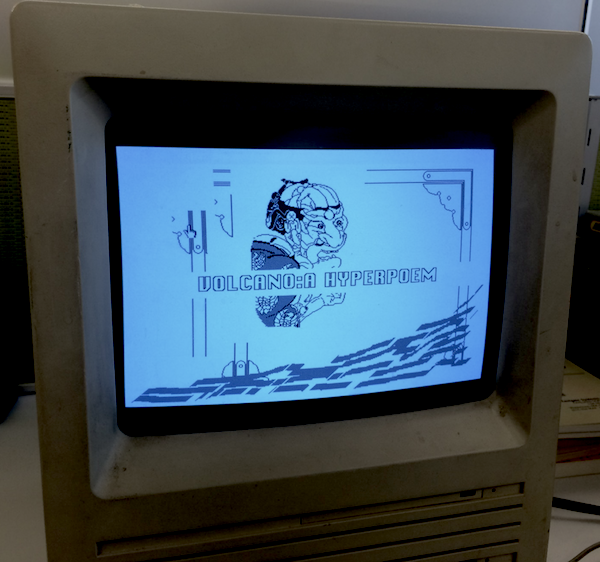

Dickey’s HyperPoems are artifacts of another time—made new and fresh again with current technology.His proficiency was obviously growing with each new work. He learned how to turn a “stack” of cards into a labyrinth—or else a mandala, a looping pattern that had fascinated him throughout his life. All of these features changed Dickey’s thinking about the possibilities of poetry, moving him away from his earlier musings over fountain pens toward what we would nowadays think of as immersive media. The poem became a compositional score, a framework for experience. He compared his new medium to Walt Disney animations as well as illuminated manuscripts, but notes that unlike these rarefied forms anyone with a computer could be thus empowered.

Several of the HyperPoems can be described as lyrically and graphically explicit erotica. Here too, Dickey exploited his medium: to progress further in a poem called “Accomplished Night,” for example, one clicks on the head of a penis. Thus to read, the reader must also touch. We can now see that these are some of the very earliest (and most explicit) digital creative works by an established LGBTQ+ author.

*

In 1994, complications from HIV tragically took Dickey’s life. The Education of Desire, a posthumous collection that appeared from Wesleyan University Press in 1996, is widely recognized as capturing some of his finest work. But the fourteen HyperPoems that were composed at the same time remained inert on his hard drive after his death. Issuing them would have meant packaging the digital files on a floppy disk—not something many publishers were willing to take a chance on. Apple then retired HyperCard in 2004, and the format became obsolete. The HyperPoems were forgotten by all but a handful of dedicated students of digital writing, who learned of them by rumor and reputation.

Photo via Matthew Kirschenbaum

Photo via Matthew Kirschenbaum

One of those devotees was myself. I knew that a laptop with copies of the HyperPoems had made its way to the University of Maryland (where I teach) as part of a fellow writer’s literary papers (nowadays, an author’s “papers” increasingly take the form of disks and hard drives and even whole computers). From there I was able to extricate copies of the original files from the antiquated operating system, and, working with Dickey’s literary executor Susan Tracz and technical experts, add them to the Internet Archive.

The Internet Archive got its start collecting web pages. Nowadays it might be best known (or most notorious) for its controversial ebook library; but, intriguingly, the Internet Archive also now archives software meant to run on obsolete systems. Using a form of technology known as an emulator, anyone can point their browser at the Internet Archive and play a game that was originally meant for an Apple II, or relive a spreadsheet program that was originally meant for the Commodore 64. HyperCard is among the software it supports. This gave us the perfect platform for publishing the HyperPoems, some 25 years after Dickey’s death (and fittingly with the help of an institution in his own home city of San Francisco).

Photo via Matthew Kirschenbaum

Photo via Matthew Kirschenbaum

Dickey’s HyperPoems are artifacts of another time—made new and fresh again with current technology. Anyone with a web browser can read and explore them in their original format with no special software or setup. (They are organized into Volume 1 and Volume 2 at the Internet Archive, in keeping with their original organizational scheme; Volume 2 contains the erotica—NSFW!) But they are also a reminder that writers have treasures tucked away in digital shoeboxes and drawers. Floppy disks, or for that matter USB sticks and Google Docs, now keep the secrets of the creative process.

Photo via Matthew Kirschenbaum

Photo via Matthew Kirschenbaum

Dickey himself, cherishing as he did circular figures and patterns, almost seemed to anticipate a digital revival in posterity. As he writes in the HyperPoem “Volcano”:

This is my letter to you. What I had

not thought to say, but to fold, as

we fold away the evening or the

butterflies, carefully, in the pattern

of stiff brocade, creasing it, making

the folds lie sharp and exact that

are only meant to crumble and

break from their own weight, years

later, when the person is opened,

when what is left is a breath of

voice, rising transparently, the logic

behind the perfume, all of what

once was sense stinging a little at

range beyond range of air.