The Long Unpredictable Life of Art: Francine Prose on Teaching James Alan McPherson to Incarcerated Students

Remembering a Dear Friend Through His Work

This spring, the second spring of the Covid-19 pandemic, I taught, under the auspices of the Bard Prison Initiative, at the Eastern Correctional Facility, a men’s maximum security prison in Napanoch, New York. The conditions for remote learning were challenging. The only screens in the Eastern school were reserved for math classes, so the humanities had to be taught on speakerphone. I couldn’t see my students, and they couldn’t see me. Also the acoustics were bad. My students could hear me, but they needed to cross the room, one by one, and speak directly into the phone in order for me to hear them.

The Bachelor of Arts Seminar was divided into two halves, to allow for social distancing in the classrooms. I taught half the students for the half the semester, and the same reading list to the other half of the students for the remaining weeks, trading off with a colleague, James Romm, who teaches classics at Bard.

I thought that teaching this way would be impossible, but, as it turned out, it wasn’t. The two-hour classes were demanding. Exhausting, in fact. But somehow the process worked, despite the “pauses” for quarantine when the whole school had to shut down.

I talked more than I might have in a traditional class. Something about being invisible created a kind of privacy, the freedom and honesty I imagine in the confessional, though of course our subject was literature, not sin. My students attended discussion groups, wrote papers, spoke up, had opinions, differed from one another and from me, and sometimes changed their minds. In other words, it was a class.

At the end of the first section, I asked my students to come to the speaker and tell me, one by one, what they’d learned from the readings and the discussions. And I remember thinking that, for most of them, it was almost as if we’d been in the same room.

*

I called the class Myth and History, mostly to link it to the other half , in which the students were reading The Iliad. Mine was the sort of class I’d been teaching at Bard College: close-reading stories and novels grouped around a loosely connective thread, studying literature through word-by-word analysis of language, subtext, how a story is told, the choices the writer has made.

There was some myth, some history: James Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues” and John Cheever’s “Goodbye, My Brother” inspired a discussion of Cain and Abel. Shalamov’s “My First Tooth” and Tatyana Tolstoy’s “Heavenly Flame” made no sense without some knowledge of Soviet history, while others—Roberto Bolano’s “Sensini” and Marian Enriquez’s “Spiderweb—required the reader to know something about the South American military dictatorships and the Latin American diaspora.

Often my students focused on a name or detail—there’s a pub in Kevin Barry’s Night Boat to Tangier named “The Judas Iscariot”—that invoked the biblical and archetypal. A few texts barely touched on history or myth. Still, I wanted to read them along with the group and hear what the students had to say. I chose these works because I admire them and because they seemed strong and interesting enough to make us think, in complex ways, about something beyond the pandemic.

*

I’d taught once before in the prison, in 2018, in person. We studied Dickens’s Great Expectations. It’s a novel I love, but also I thought it might interest the class that Dickens spent part of his childhood in the Marshalsea Prison, and that Magwich, a convict, is more heroic than its nominal hero, Pip. The 19th century diction took some getting used to. It helped to read passages aloud. At the end of the class my students asked me which Dickens novel they should read next.

I was often surprised by what these incisive, hard-working and thoughtful students said, partly because their lives were so unlike mine. They loved the scene in which Pip, newly a gentleman, returns to his town and is taunted and mocked by a character known only as Trabb’s Boy, the tailor’s assistant, mired for life in everything that Pip has escaped. My students were attuned to the disruption involved in crossing, or in trying to cross, class divisions. That was one of Dickens’s obsessions: how it feels to lead a different life than the life you expected, how deeply those imagined and real lives are determined by social mobility, or its absence. There’s a touching scene in Little Dorrit: En route to Rome, Little Dorrit contemplates the strangeness of the fact that she used to be poor and now she is riding in a carriage.

*

During the pandemic, I taught stories I had taught before. There were passages I knew almost by heart. But reading these stories with a different group changed the way I read them.

The nameless narrator of Cheever’s “Goodbye, My Brother” is not an appealing character: small in spirit, willfully blind, deluded about himself and his family. His sad life, teaching high school on Long Island, watching in politely suppressed panic as he and his wife age, all of that is (I think) meant to inspire our compassion, even admiration for his final rapturous hymn to a summer morning. But this time it occurred to me that teaching high school and vacationing in the beachfront home of one’s nasty alcoholic family might sound pretty good compared to spending twenty years in prison.

So, what has he got to complain about? Perhaps, I told my class, his loneliness and blindness—his cluelessness about himself and the people around him—were touching, regardless of his privilege. My students said, No. What made him sympathetic was his family: He didn’t know what family meant or why you wanted and needed the love and support of the people who love you.

*

One of the stories I taught at Eastern during the Covid pandemic was “Gold Coast,” by James Alan McPherson.

I met Jim McPherson in 1967, in a writing class at Harvard, where I was an undergraduate and he was attending Harvard Law School. He was writing “Gold Coast” in that class, that semester.

Jim became a dear friend. I was flattered that he thought of me as a friend, which suggested to me that I must be more worth knowing than I’d thought. I saw him every so often in Boston and New York, on panels, prize juries, occasions like that. It was more fun to see him in Iowa, where he became a life-changing teacher at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop, which he had attended. Among his students were Gish Jen, Samantha Chang, Yiyun Li, ZZ Packer, T. Geronimo Jackson, and Eileen Pollack.

It was the only time that I was glad to be on speakerphone, because each time my students read aloud from “Gold Coast,” I began to cry.

I spent two semesters teaching at Iowa, and the nicest times I spent with Jim were out in the country, having dinner at the house of our friend, Connie Brothers, the long-time administrator, heart and collective memory of the Workshop. Jim’s daughter, Rachel, became a family friend. I last saw him a few years before his death, in Iowa City, in 2016.

“Gold Coast” is from his first collection, Hue and Cry (1969). His second book, Elbow Room, won the 1978 Pulitzer Prize, and in 1981 he received one of the earliest MacArthur awards. In 1998 he published a book of essays, Crabcakes: A Memoir (1998) and another, A Region Not Home: Reflections on Exile appeared in 2000.

“Gold Coast” remains my favorite of his works, perhaps because it still delivers that shock of realizing that someone I actually knew, a fellow student, had written something so amazing.

*

It’s a difficult story to summarize, since so much depends on tone, the quiet clarity, the honesty mixed with sly irony and a reserve about what the writer trusts us to figure out. Here is the opening paragraph, for a sense of that tone and of how much information can be compressed into a few sentences:

That spring, when I had a great deal of potential and no money at all, I took a job as a janitor. That was when I was still very young and spent money very freely, and when, almost every night, I drifted off to sleep lulled by sweet anticipation of that time when my potential would suddenly be realized and there would be capsule biographies on my life of dust jackets of many books, all proclaiming: “…He knew life on many levels. From shoeshine boy, free-lance waiter, 3rd cook, janitor, he rose to…” I had never been a janitor before and did not have to be one and that is why I did it. But now, much later, I think because it is possible to be a janitor without really becoming one.

We follow the narrator, Robert, to Cambridge parties at which the other guests—Harvard graduate students in philosophy and law—feel uncomfortable socializing with (as Robert describes himself) “an apprentice janitor.” They try “to make me feel better about my station while wondering how the hell I managed to crash the party.” Robert reels off the things one needs to learn before becoming a full-fledged janitor: human nature, for one thing. “Race nature,” for another.

“Because,” I would say in a low voice looking around lest someone else should overhear, “you have to be able to spot Jews and Negroes who are passing.”

After a good pause, I would invariably be asked, “But you’re Negro yourself, how can you keep your own people out?”

At which point I would look terribly disappointed and say: “I don’t keep them out. But if they get in it’s my job to make their stay just as miserable as possible…It’s Janitorial Objectivity,” I would say to finish the thing as the speaker began to edge away, “Don’t hate me,” I would call after him to his considerable embarrassment. “Somebody has to do it.”

*

Over the phone, I asked my students what was happening in the scene. One of them said that Robert was a Black man joking around, trying to be sociable, to get along, to do what a Black man has to do in a room full of white people.

I asked one of them to read the passage aloud.

Afterwards, there was a silence. Another student said that actually… maybe Robert was being “impish” and “mischievous.” The words hovered there for a moment.

Another silence, and a third student said that maybe Robert thought he was smarter than the other guests, maybe he was smarter, and he was messing with their heads, having fun by putting them on edge about a “tough, uncomfortable subject: race.”

One by one, my students said, “That’s right. That’s what he’s doing.”

*

Everything in the story seems straightforward even as it compels us to reread it, and to think harder. Robert is working in an apartment building in Harvard Square that has seen better days—“a funny building, because the people who lived there made it old.” Some of its tenants have lived there forever; none are rich. His boss is a lifelong janitor, James Sullivan: alcoholic, elderly, ill, living with a crazy wife and crazy dog, surviving at the whims of tenants he despises. He can’t really haul trash cans any more, which is why the building management has hired Robert.

Sullivan rises to the challenge and the flattery of having a subordinate, and he lectures Robert on his janitorial rights. “Don’t let any of these girls shove cat shit under your nose. That ain’t your job.” Lest we pity Sullivan, McPherson intersperses the janitor’s avuncular advice with anti-Semitic rants. But, as Robert comes to believe,

Sullivan did not really hate Jews. He was just bitter toward anyone better off than himself…He lived with his wife on the second floor and his apartment was very dirty because both of them were sick and old, and neither could move very well…There was a smell of dogs and cats and age and death about their door, and I did not ever want to have to go in there for any reason because I feared something about it I cannot name.

As several of my students pointed out, the story is about friendship, not a friendship between equals; the power balance is complicated. Sullivan is white, poor, old, miserable, aware of his misery, and will never be anything but a janitor. Robert is Black, young, talented, optimistic, confident, a writer, and he has his whole life in front of him.

Here was a young Black man with so much more going for him than his elderly white boss—and making us rethink our easy assumptions about race and class. Not that Robert occupies his own post-racial bubble, or that Jim McPherson believed that such a bubble existed. In the story, Robert and his white girlfriend, Jean, are worn down by the pressures of being an interracial couple in Boston in the 1970s. They play a game called “Social Forces,”

the object of which was to see which side could break us first…The last round was played while taking her home in a subway car, on a hot August night, when one side of the car was black and tense and hating and the other side was white and of the same mind. There was not enough room on either side for the two of us to sit and we would not separate; and so, we stood, holding onto the steel post through all the stops, feeling all the eyes, between the two sides of the car and the two sides of the world. We aged. And getting off finally at the stop which was no longer ours, we looked at each other again expectantly, and there was nothing left to say.

Like everything in the story, it’s not just race, but also class. Jean is rich. She and the janitor, James Sullivan, hate each other on sight.

After the break up, Robert begins spending more time with James Sullivan, drinking beer and talking in Robert’s apartment.

I discovered that he was very well read in history, philosophy, literature and law. He was extraordinarily fond of saying, “I am really a cut above being a building superintendent. Circumstance made me what I am.” And even though he was drunk and dirty and it was very late at night, I believed him and liked him anyway because having him there was much better than being alone.

*

James Alan McPherson was born in Savannah, Georgia, in 1943, decades before the South was officially desegregated. His mother was a waitress, his father a master electrician who couldn’t get work because he was Black. Jim held the jobs that Robert imagines listing on his dust jacket flap; also, Jim was a waiter on the railroads, an experience he drew on for his story, “Solo Song for Doc.” He attended Morgan State University, then Morris Brown College. It must have been obvious, how gifted he was. By the time he got to Harvard Law School, I think he was already deciding that he wanted to be a writer, not a lawyer. He became a contributing editor at The Atlantic, for which he wrote essays and long form journalism.

At the time we met, he was extremely handsome, soft spoken and shy. This was when you could still smoke in class, and once I noticed he was dropping his ashes in the flip-top of his Marlboro box because he couldn’t bring himself to ask anyone to pass him the ash tray.

We were at an age when another writer’s talent can make you want to quit forever. Every word I put down, every thought I had, seemed trivial.

There was something fierce and sharp in his look that softened over time, but his low voice and his idiosyncratic timing remained the same. His side of the conversation came in short bursts of often gnomic speech, delivered under his breath. Sometimes it took a moment to understand the perceptive, profound, hilarious thing he’d just said. You had to listen because he made layered, complex statements that no one else would think of, let alone say out loud. His humor was nuanced and often oblique. For a while he had a business card and an answering machine message that said, “Mr. Jefferson is not at home, he’s down at the cabins making contradictions.” In the introduction to an interview with Jim that appeared in the Winter 2017/2018 Iowa Review, Cammy Brothers writes, “He was never capable of small talk, and everything he said cut to the heart of the matter. He could be cryptic, wise, subversively funny or say nothing at all.”

He always paused a beat before he spoke, and you learned to wait.

*

The class I took with Jim was on a high floor of the Holyoke Center, designed by Jose Luis Sert. In those days, in Cambridge, a ten-story structure occupying an entire block was controversial, arousing the sort of objections that today might be inspired by a huge high-rise mega-mall that changes the character of a neighborhood. The building housed administrative offices, classrooms and meeting rooms, and the student health service. It was where you went on official business or to visit friends who’d had breakdowns.

A long narrow room, a long narrow table. Windows along one side. A cramped and humble version of today’s corporate boardroom.

Our class predated email and the photocopy machine. Making enough copies of a story for one’s classmates to read required typing on a special paper and mimeographing it, which took time. Mostly we read our stories aloud, which turned out to be useful. We could hear how it sounded, and tell when people were paying attention or drifting off.

When it was Jim’s turn to read, he couldn’t.

He whispered a few words, then stopped, then whispered a few more. Then he stopped. It was clearly hard for him. I remember how tense we were.

Our teacher asked if Jim wanted him to read the story for him.

Jim said yes. Thank you. He handed the manuscript over.

Our teacher began to read. “That spring, when I had a good deal of potential…”

When he reached the last line, no one spoke for a long time. No one had any suggestions for improvement, or none that I remember.

*

I wrote nothing for the rest of the semester. I’m not sure that anyone (besides Jim) did. We were at an age when another writer’s talent can make you want to quit forever. Every word I put down, every thought I had, seemed trivial. Years would pass before I wrote anything that I Iiked. It wasn’t Jim’s fault, obviously. It’s a good thing when a writer’s work raises the bar high enough to make you rethink whatever you thought you were doing.

Jim’s friends believed that he was a genius. We weren’t surprised or jealous when he got that early MacArthur. We said, Right. It’s the genius grant.

*

At the end of “Gold Coast,” Robert has quit his apprentice janitor job. Walking through Harvard Square, he sees James Sullivan and his wife hobbling along, struggling with their shopping bags:

I had an instant impulse to offer help and I was close enough to touch him before I stopped. I will never know why I stopped. And after a few seconds of standing beside him and knowing that he was not aware of anything at all except the two heavy bags waiting to be lifted after his arms were sufficiently rested, I moved back into the stream of people which passed on the left of him. I never looked back.

My Eastern students disapproved. The word they used was cold. One of them said that God has commanded us to help the elderly. Then another one said, “There are friends you used to have, it isn’t good for you to be around them, when you see them, you just keep walking.”

I quoted a friend who said that Robert’s compassion for James Sullivan is so intense that it registers as shame. It proves that he is a writer, already seeing through the eyes of another person. My students agreed that this could be true, but they didn’t sound fully convinced. They tended to judge characters by what those characters did. When we read Lewis Carroll, a few of them said that Alice was stupid for following a rabbit down a rabbit hole and drinking and eating things without knowing what they are.

Then one student said that Alice was imaginary, it wasn’t real, that Alice in Wonderland was all about the imagination. He said that the power of the imagination is what makes us human. Two more students came to the speakerphone, separately, to agree.

*

Quite a few my BPI students read beautifully, unusually so, out loud. Maybe it was a coincidence, maybe they’d read aloud in other classes. I didn’t ask. They read the words as if they meant something. They understood where the stresses belonged, where the punctuation breaks came. They knew when to take a breath. They read like writers, like actors. Better than actors.

Whenever they read aloud from “Gold Coast,” I would think of Jim being unable to read it, all those years ago. I’d think of how much time has passed since then. I’d think of the shocking and truly incomprehensible fact that Jim could possibly be dead.

Also, it seemed to me that I was hearing the story in the voice—the voices—in which the story was meant to be read.

It was the only time that I was glad to be on speakerphone, because each time my students read aloud from “Gold Coast,” I began to cry.

I was grateful that they couldn’t see me. I don’t like to cry in class. It upsets the necessary and delicate balance of power. For the students, it’s probably a little like seeing a parent break down. Destabilizing. Disturbing. Embarrassing for everyone.

.*

Some time ago, at dinner, I asked a group of Bard colleagues if there were any texts they’d stopped teaching because they made them cry in class. One said Tagore’s Gitanjali. Another mentioned Boccaccio’s “Griselda,” from The Decameron. A third said Cordelia’s death in King Lear. Years ago, the novelist Diane Johnson told me she couldn’t teach the passage about the funeral of Anne Bronte in Elizabeth Gaskell’s Life of Charlotte Bronte without bursting into tears. I taught it once, as an experiment, and the same thing happened to me.

I have stopped teaching Chekov’s “In the Ravine.” The reckless murder of Lipa’s darling baby is simply too painful to put a class through. Other passages that leave me in tears, or on the edge, are the ending of James Joyce’s “The Dead”; Nanny’s speech in Uncle Vanya (“The geese cackle, the geese stop cackling”) and Sonya’s speech at the end (“We must work, Uncle”). Emily’s “Goodbye, World” monologue in Our Town. Sylvia Plath’s “The Moon and the Yew Tree.”

I often teach Martin Luther King’s “I Have Been to the Mountaintop” sermon. I teach it as a perfect example of the power of rhetoric and repetition. King is describing the aftermath of the first attempt on his life; a pen knife lodged so close to his heart that the doctors told him that, had he sneezed, he would have died. King then lays out the entire history of the Civil Rights movement, beginning each event with, “If I had sneezed.”

“If I had sneezed, I wouldn’t have been here in 1963, when the black people of Birmingham, Alabama aroused the conscience of this nation, and brought into being the Civil Rights Bill. If I had sneezed, I wouldn’t have had a chance later that year, in August, to try to tell American about a dream that I had had. If I had sneezed, I wouldn’t have been down in Selma, Alabama, to see the great movement there.” By the time we get to “I’m so happy that I didn’t sneeze,” it’s impossible not to choke up, even if you try to forget the fact that he delivered the sermon on April 3, 1968, the day before he was assassinated.

It occurs me that, for all their obvious differences, what the James Joyce passage, the MLK sermon, the “Let us work, Uncle Vanya” speech, the Plath poem, and my students reading “Gold Coast” share in common is: musicality. The repetitions, the way the words are arranged, the rhythms of the language are unusually close to poetry and music, which as everyone knows have shorter paths to the heart—and the tear ducts.

*

For years I couldn’t hear Mozart without dissolving, no matter where I was, or who was playing. My sons’ rural public school eighth-grade orchestra scratching out their version of the Jupiter Symphony. A master chorus singing the Requiem in the Santa Maria Aracoeli church on the Capitoline Hill in Rome. I’d think of Mozart in his pauper’s grave, having written that gorgeous music, playing now, in this auditorium, this church.

Tears would well up. From where? Perhaps I should say: I am not a big crier. If I were to rate myself, for how often I cry, from zero being never to ten being always in tears, I would in general average a three, allowing for stretches of tens and zeros.

In his charming and instructive study, Pictures and Tears, art historian James Elkins explains how puzzled he was to learn that the painter whose work makes the greatest number of people cry is Mark Rothko. Trying to understand, Elkins spent time at the Rothko chapter in Houston, watching people, reading the visitors comment book.

He then goes on to write about the social history of weeping. He solicits and gets letters about the subject. He takes a survey and classifies various kinds of tears:

Weeping over bluish leaves. Crying at the empty sea of faith. Crying at God. False tears over a dead bird. Crying in lonely mountains.

It appears from my survey that time is one of the principal reasons people cry at paintings. Some are struck when they return to a museum they hadn’t visited for years and see the same pictures hanging from the same walls. That made several of my correspondents think of their own lives and of how they are ebbing away. One person said he realized the painting he was looking at would still be there long after he had died. Now there’s a depressing thought, or, if you prefer, a genuinely sad one.

Of course, my sense of the passage of time was part of my reason for crying when my students read “Gold Coast.” But it was more than that. It was like hearing the Jupiter Symphony in that middle-school auditorium, like listening to Mozart’s Requiem in that glorious Roman church, like watching great actors perform Uncle Vanya.

How should we classify those tears?

Crying from being surprised and moved by the long unpredictable life of art.

______________________________________________

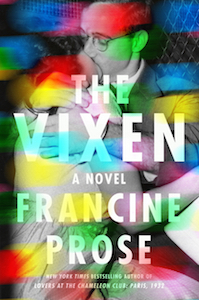

Francine Prose’s The Vixen is out now.

Francine Prose

Francine Prose is the author of twenty-two works of fiction including the highly acclaimed The Vixen; Mister Monkey; the New York Times bestseller Lovers at the Chameleon Club, Paris 1932; A Changed Man, which won the Dayton Literary Peace Prize; and Blue Angel, which was a finalist for the National Book Award. Her works of nonfiction include the highly praised Anne Frank: The Book, The Life, The Afterlife, and the New York Times bestseller Reading Like a Writer, which has become a classic. The recipient of numerous grants and honors, including a Guggenheim and a Fulbright, a Director’s Fellow at the Center for Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library, Prose is a former president of PEN American Center, and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. She is a Distinguished Writer in Residence at Bard College.