The Long Tradition of Writers Needing Ritual

On Taking Inspiration From Famous Authors' Creative Processes

I am writing this at a writers’ residency in the town of Ghent in Hudson Valley. I’ll be here for a month, and my aim is to finish this book that I imagine you, dear reader, holding in your hands in the not-too-distant future. There are words to be put on the page, but the only way that is going to happen is if I stick to my rituals.

The writer Patricia Highsmith once said that she was rarely short of inspiration; she had ideas, she said, “like rats have orgasms.” I cannot make the same claim. I don’t think writers need ideas so much; what they really need is time.

Or, more accurately, the need is for those conditions of work, the meeting of place and habits, that allow the right words to emerge. I have on my desk here a book called Daily Rituals. It offers short accounts of how writers and artists work. The quotation from Highsmith is something I came across in that book. And the detail that Highsmith, probably in an effort to keep distractions to a minimum, ate the same food every day: American bacon, fried eggs, and cereal.

According to literary legend, probably false, Edith Sitwell used to lie in an open coffin for a while before she began her day’s work. This was supposed to serve as inspiration for her macabre writing. Maya Angelou could work only in hotel or motel rooms. Truman Capote couldn’t begin or end anything on a Friday. Igor Stravinsky performed headstands when he needed a break, and Saul Bellow did 30 push-ups. For the work to go on, John Cheever required erotic release.

These examples appear to us as oddities, but what needs to be stressed is the importance of ritual in the creation of work. I tell my students that they must “write every day and walk every day”. It is not essential that they write a lot; only 150 words each day is enough. All that matters is the routine.

In Daily Rituals the dancer Twyla Tharp presents the following account of what she does after waking up at 5:30: “I walk outside my Manhattan home, hail a taxi, and tell the driver to take me to the Pumping Iron gym at 91st Street and First Avenue, where I work out for two hours. The ritual is not the stretching and weight training I put my body through each morning at the gym; the ritual is the cab. The moment I tell the driver where to go I have completed the ritual.”

According to literary legend, Edith Sitwell used to lie in an open coffin for a while before she began her day’s work.

I understand what Tharp is saying. When I lace my boots, before stepping out for my walk, I’m entering a ritual. I’m mindful of the notepaper and the small yellow pencil in my pocket. The work of writing has begun. I was pleased to find out in Daily Rituals that it is extremely common for writers and artists to go on walks. As important as the act of shutting the door of the study has been the act of opening it and stepping out for a stroll. Gustave Flaubert, Charles Dickens, and Leo Tolstoy were all walkers.

My rituals become more formalized, even concentrated, in a situation like this writers’ residency. The work of reading and writing goes on through the day, interrupted by walks along the country road outside or on the grass that stretches out to the surrounding hills. The writers don’t see much of one another during the day, but we gather together for dinner at 7:30. Then, soon after the dinner plates have been cleared, I look forward to table tennis. Although I brought with me a new yoga mat, thinking that I’d like to stretch every day, it has stayed rolled up in the corner of my room. I’m satisfied with my routine, happy that I’m able to play table tennis, and sometimes even mixing drinking shots of bourbon into the game. (This is the place, of course, to insert a passage from Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice: “Who can unravel the essence, the stamp of the artistic temperament! Who can grasp the deep, instinctual fusion of discipline and dissipation on which it rests!”)

My first act on waking up is to pour the coffee from the thermos (I make the coffee in the communal kitchen each night before going to bed) and sit down at the desk to write. It appears that at least one-third of the writers and artists featured in Daily Rituals mention their dependence on coffee. I’m not surprised. What surprises me more is that writers such as Graham Greene and Jean-Paul Sartre relied on amphetamines for their writing. Then there was W. H. Auden, who took “a dose of Benzedrine each morning the way many people take a daily multivitamin.”

I don’t know about amphetamines, but I can attest to the power of books. I have brought with me to this residency titles that appear elsewhere in these pages: books that I turn to when I’m stuck or need inspiration. (Today’s text has been Insectopedia, by Hugh Raffles. A work of astonishing breadth and beauty. Very quickly you learn about the nearly unimaginable fecundity of insects and the limits of the categories we have assigned to them. What you also realize is that Raffles has produced his own organizational principle for his Insectopedia. This innovative arrangement, not to mention the gorgeous language and teeming imagery, is closely allied with the book’s aim: to present knowledge about the “astonishing perfection” of “the billions of beings” that surround us.

A sense of strangeness of the world and, accompanying it, a feeling of awe give to many of its pages the same narrative quality that one associates with the fiction of W. G. Sebald or Michael Ondaatje.) I’ve also been reading just before falling asleep the diary of Virginia Woolf. The last passage I marked was from an entry made on Wednesday, July 13, 1932: “I’ve been sleeping over a promising novel. That’s the way to write. I’m ruminating, as usual, how to improve my lot; and shall begin by walking, alone, in Regent’s Park this afternoon.”

__________________________________

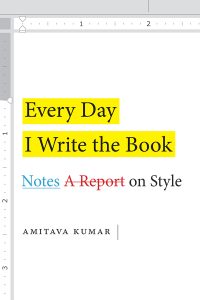

Excerpted from Every Day I Write the Book: Notes on Style by Amitava Kumar. Copyright © Duke University Press 2020.

Amitava Kumar

Amitava Kumar was born in Ara, India, and grew up in the nearby town of Patna. He is the author of the novel Immigrant, Montana, as well as several other books of nonfiction and fiction. He lives in Poughkeepsie, New York, and teaches at Vassar College.