The summer was endless in Tasmania that year. None of the normal rules held. There were no spring rains no summer rains. Each day was hot or hotter than the last. For all that though, it was not a bright or happy summer. Out in the island’s woodlands there were dry lightning storms that lasted days, thousands upon thousands of lightning strikes igniting small fired everywhere. The rainforests, once met mystical worlds, were now dry struggling woodlands, and the fires took, and the fires are; soon, the fires were the only news; they came closer or they drifted away, they advanced or they halted; the point was that wherever they were they continued to inexorably grow and with them the infernal, oppressive smoke, the cinder storms, the reign of ash, and the island’s capital filled with the displaced listlessly waiting for the fires to end so that they might return to their homes and their lives.

And yet life itself seemed on hold.

There was a great waiting though for what no one knew. There was an edge and a tension as week after week the fires slowly reduced the ancient forests, the exquisite heathlands and alpine gardens of the island’s west and highlands into the ash that Anna, when home seeing her mother, woke each morning to find speckling her Airbnb bed sheet, the fires that rained on the island’s old city tiny carbonized fragments of ancient fern and myrtle leaf, perfect negatives that on her touching vanished into a sooty smear, and all that remained of the thousand-year-old King Billy pines and ancient grass trees, the pencil pine groves, the stands of panda and rich, the great regnans along with the button grass plains and the tiny rare mountain orchids, all that was left of so many sacred worlds was Anna’s soot-stained bed sheet.

The smoke had turned the air a tobacco brown, the blinding brilliance of the island’s blue skies glimpsed only when the winds blew a small hole in the pall that sat over much of the island. The smoke never seemed to life and on the worst days reduced everyone’s horizon to a few hundred years and enclosed the world in a way that felt claustrophobic. The sun stumbled into each day a guilty party, a violent red ball, indistinct in outline, shuddering through the haze as if hungover, while in the ochry light smoke smothered every street and the smoke filled every room, the smoke sullied every drink and every meal; the acrid, tarry, sulfurous smoke that burnt the back of every throat and filled every month and nose blocking out the warm gently smells of summer. It was like living with a chronically sick smoker except the smoker was the world and everyone was trapped in its fouled and collapsing lungs.

*

And that Wednesday afternoon, not even an hour earlier, it was this same smoke that burnt Anna’s throat and made her cough while she was driving into the Argyle Street car park opposite the Royal Hobart Hospital. On raising her left hand to cover her mouth something seemed strange. She had the odd thought that one of her fingers was missing. It was such an odd thought that she immediately dropped both it and her hand/

As she turned onto the fourth-storey ramp, she brought her left hand to the stop of the steering wheel. Once more it seemed not quite right. She glanced down. It wasn’t quite right. She saw her thumb and counted three fingers. She swung the wheel around and then swung it back. This time she saw a finger was definitely not where a finger should be and where it should be, next to the little finger, there was, to be precise about it, thought Anna, well, precisely nothing.

She twisted her head around, stealing looks here and there in the car park’s crepuscular light, hoping perhaps to see the lost finger leap up. She looked at the hire car’s dash as if it might have fallen there. She ran her remaining fingers through the cup holder console but felt only grit and hire car papers. Several times she glanced down at the seat between her legs, and finally the floor.

And realizing that this quixotic quest was ridiculous, because you don’t just lose a finger like a key or a phone, she jerked her hand—now at nine o’clock on the steering wheel—to twelve o’clock, dragging the wheel back around and nearly driving into an oncoming car as she did so. The other driver beeped, she braked, swerved, halted, and raising a shaking hand to her forehead she felt not relief but a surge of horror.

Between her little finger and her middle finger, where her ring finger had once connected to her hand, there was now a diffuse light, a blurring of the knuckle joint, the effect not unlike the photoshopping of problematic faces, hips, things, wrinkles and sundry deformities, with some truth or other blurred out of the picture.

And so too now, it seemed, one of her fingers.

She stared closely at her hand for a good minute. It wasn’t

It a strange illusion or delusion. There was—it was undeniable—no ring finger. She wiggled her thumb and three remaining fingers. They seemed fine, doing the finger things fingers do. There was no pain. There was no immediate sense of ache or loss.

There was just a vanishing.

*

Anna dropped her hand and put the odd event down to the exhaustion she was feeling. Her day had begun with Tommy waking her at two in the morning with a phone call to say Francie had taken a bad turn and had been rushed by ambulance to the Royal Hobart Hospital. It was irritating to say the least, thought Anna, because there was no end to Francie’s bad turns which, in hindsight, were never really as bad as Tommy made out.

Tommy’s frequent updates on their mother’s health sometimes bordered, Anna felt, on the ludicrous. She and Terzo even had a running joke that Tommy had called to say he was very worried about Francie eating/talking/breathing. He seemed to feel it was his duty to keep his siblings abreast of their mother’s many infirmities as though they constituted some evidence of a major breakdown in her health.

It was true that there had been a few problems in recent times but each had, after a while, resolved itself. Some years before, Francie had started behaving strangely and her doctor diagnosed dementia. Her walking grew odd, a bizarre half-lollop, half-stagger—like a horse on a bad trip, as Terzo said—and the doctor diagnosed Parkinson’s. When she collapsed and was rushed to hospital it was discovered that its as neither dementia nor Parkinson’s but rather something else altogether, that she had fluid on the brain, that it was a condition called hydrocephalus, and that it could be relieved by putting an internal shunt up through the back of her neck into her brain, draining the excess fluid into her stomach.

The procedure, frightening as it sounded, proved a success. The oddities of gait and confusions of personality disappeared and, re-emerging into her old self, Francie returned to her life and home and they, her three children, to theirs.

In Anna and Terzo’s case, the children who had left the island long ago, that meant phoning their mother more regularly and flying in to see Francie for a day or two every few months. For Tommy, who never left, who was a failing artist and occasional laborer and crayfishing deckie, who, to be frank, Anna thought in her crueler moments, had never really done anything, it did mean a little more. But then Tommy had more time to do more: time to help out with small things—doctors’ visits, cooking, shopping, driving Francie to meet her old friends for afternoon tea.

A year passed, and another and another, and three years after the hydrocephalus operation Francie was diagnosed with a slow-developing form of cancer, low grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma. She embarked on a mild course of chemotherapy and at its end, amazingly, went into remission. Francie was, as she herself said, the fittest old corpse in Christendom.

*

And in this way, as if everything had somehow returned to normal, as though tomorrow could never be so very different from today, as if this slow accumulation of ailments and pattern of declining health was of no consequence, almost five years passed, and in those years Anna felt she accomplished so many things she had long wished for.

She had stumbled into the design of Durand House after one of her architectural firm’s senior partners died. The resulting building—a sickle-shaped, steel-spine structure wistfully cantilevered out over a Blue Mountains cliff, a holiday home for the well-known retailer Tony Durand—was hailed as a triumph. Along with a measure of excited architectural babble, it won several national prizes and later a global award for design. But it was for Anna no more or less than making a building from a childhood memory of a eucalyptus leaf.

In no small part because of that success, she was made a partner in the firm. And she met Meg, who worked as a project manager with the construction company that had built Durand House. Anna had seen her sound their office, a professional woman to the point of anonymity, then one weekend bumped into her a café. Meg was wearing yoga pants, dark hair in a top knot that accentuated her cheekbones and her smile. She sat with one leg casually tucked under the other, revealing a strong calf. Sit next to me, she said.

So it began.

__________________________________

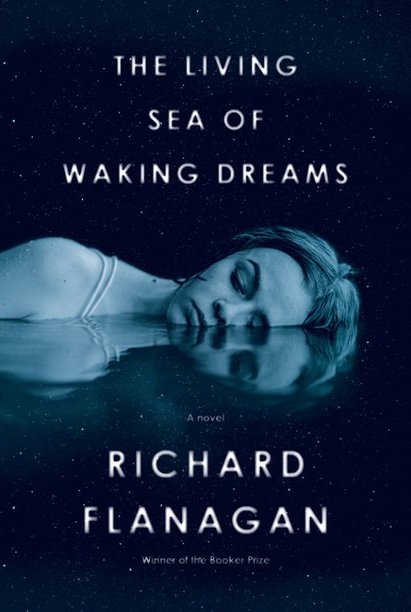

Excerpted from The Living Sea of Waking Dreams by Richard Flanagan. Excerpted with the permission of Knopf Publishing Group. Copyright © 2021 by Richard Flanagan.