The Little Known, Much Loved Cookbook That Was Ahead of Its Time

On Patience Gray's Honey from a Weed

Patience Gray’s Honey from a Weed is one of the most important and best-loved cookbooks of the 20th century, yet its author remains little known beyond a small circle of food writers and critics. Such is the fate, perhaps, of a woman who lived for more than 30 years in a remote corner of southern Italy—without electricity, modern plumbing, or telephone—and liked to say, deliberately misquoting Gertrude Stein, that she wrote only for herself and friends. As her publisher Alan Davidson once observed, “She simply wished her accumulated knowledge to be preserved in a permanent, beautiful form for the benefit of her grandchildren.”

Alan rescued the typescript from oblivion, and when Honey from a Weed was published in 1986, it was immediately hailed as a classic. Gourmet described it as “magically idiosyncratic” and placed Patience alongside Patrick Leigh Fermor, Freya Stark, and Elizabeth David. In an early review of Honey from a Weed, John Thorne wrote that only D. H. Lawrence was her equal “in conveying the rich physical sensuality of Mediterranean life.” Cookbook editor Judith Jones, who reviewed the manuscript for Knopf but knew that they would never dare publish it, said she fell in love with it and copied several pages “to read again when I needed that kind of refreshment.” In an essay titled “Eat or Die,” the late novelist Jim Harrison called Patience “a wandering Bruce Chatwin of food.”

In other words, she was much more than just a food writer. Honey from a Weed—part recipe book, part travelogue, and part memoir—offered a singularly evocative portrait of a remote and fast-disappearing way of life. Following the publication of Honey from a Weed, food writers sought Patience out and many made the pilgrimage to Puglia to see her, a testament to the power of her work. She was profiled by Paul Levy, appeared on the BBC’s Food Programme with Derek Cooper, and was featured along with her partner, the Belgian sculptor Norman Mommens, in the Italian magazine Casa Vogue.

Although she enjoyed the attention, Patience was rather guarded about her own life. This applied not only to visiting journalists and food writers but to friends and family as well. There was “an aura of secrecy about her,” a sense that her past was somehow shuttered, which Patience did little to dispel. “Patience loved secrets, secret rooms, dark corners, mysteries and so on,” her friend Ulrike Voswinckel recalled. This aura of secrecy was enhanced by her interest in astrology and mysticism and her vast folkloric knowledge of edible plants and mushrooms. She shared her workspace in Puglia—to which others were rarely admitted—with a large black snake and often ruminated on the symbolic meaning of the scorpion, which happened to be Patience’s astrological sign. She was born on Halloween. It is perhaps not surprising then that several people, including Paul Levy in his profile for the Observer and the Wall Street Journal, described Patience as a modern-day witch.

Yet in the few interviews she gave, she proffered tantalizing clues to her earlier life: a great-grandfather who was a Polish rabbi; surviving the war years in a primitive cottage in rural Sussex, where she first learned to forage; raising two children out of wedlock in postwar London. Before she embarked on her Mediterranean odyssey in 1962, Patience worked closely with some of the leading designers and landscape architects of her day. She edited a book on indoor plants and gardens in 1952, was assistant to the head of the school of graphic design at the Royal College of Art until 1955, and in the late 1950s and early 1960s, designed textiles for Edinburgh Weavers and wallpapers for Wallpaper Manufacturers Limited. She was also the first editor of the “woman’s page” at the Observer from 1958 to 1962, and her weekly column reflected her background in art and design.

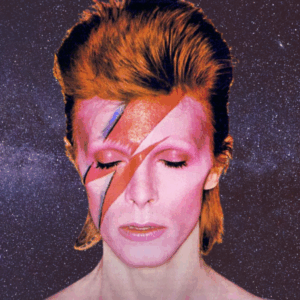

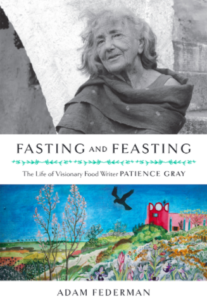

Portrait of Patience taken in 1959 by her colleague at the Observer. Photo by David Sim.

Portrait of Patience taken in 1959 by her colleague at the Observer. Photo by David Sim.

I knew none of this when I happened upon Patience’s obituary in the quarterly food journal The Art of Eating in 2005. In the reminiscence, the magazine’s editor, Ed Behr, who visited Patience on two occasions at her farmhouse in Puglia, called Honey from a Weed “one of the best books that will ever be written about food.” It was unusually high praise from a discerning and often unsparing critic. Soon after, I discovered a copy of Honey from a Weed on a shelf in my parents’ kitchen. A single recipe was marked: “Catalan veal stew with prunes and potatoes,” described in a note scribbled in the margin as “fabulous, rich, full, and simple to make.”

I read the book from cover to cover and was swept away by its originality, its sense of urgency—the introduction is a powerful argument in favor of eating seasonally—and its vivid descriptions of fasting and feasting. It was unlike anything I’d ever read before. Yet despite the book’s intensely personal nature, it revealed little of its author’s past, with the exception of a fleeting and somewhat cryptic reference to gathering fungi in a wood in Sussex during wartime. Naturally I wanted to know more.

I soon learned that not only had Patience written one of the best-selling British cookbooks of the 1950s, Plats du Jour, but she had also had a major hand in translating Larousse Gastronomique—the first English-language edition was published in 1961. In addition, she had written a collection of autobiographical essays (Work Adventures Childhood Dreams), a travelogue of a year spent on the Greek island of Naxos (Ring Doves and Snakes), and had edited a collection of Catalan recipes recorded by her friend Irving Davis. I found the little I knew of Patience tremendously compelling and sent a letter to her daughter, Miranda, who had illustrated her posthumously published book, The Centaur’s Kitchen. I was told that all Patience’s letters, unpublished work, and other papers were still in Puglia, where Patience’s son, Nicolas, now lives. In 2006 I made my first visit.

The long drive from the train station in Lecce, a city famous for its baroque architecture and equally refined pastries, takes you through austere and monotonously flat agricultural land dominated by centuries-old olive trees, ancient ruins, and newly built solar arrays. Apart from the glimpses to the south of pale blue sparkling sea, one feels dropped in the middle of a somewhat forsaken and otherworldly landscape.

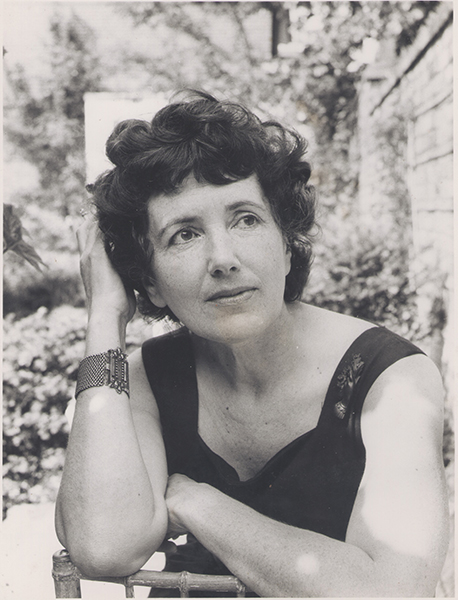

Norman and Patience at Spigolizzi in 1971. Photo by Francesco Radino.

Norman and Patience at Spigolizzi in 1971. Photo by Francesco Radino.

The old farmhouse where Patience and Norman lived, Masseria Spigolizzi, sits atop a high point overlooking the Mediterranean, not far from the villages of Presicce and Salve, at the very southern tip of the heel of Italy. On clear evenings one can see the sun set over Calabria. From the nearby eastern shore of the peninsula, Albania and the island of Corfu are visible on clear days. Now a popular summer venue for European tourists, the region still seems thinly populated.

When Patience and Norman settled here in 1970, the countryside was largely empty, owing to decades of rural flight. Few outsiders had heard of the Salento or bothered to visit, let alone make the area their home. In his magisterial wartime picture of life in nearby Basilicata, Christ Stopped at Eboli, Carlo Levi noted, “No one has come to this land except as an enemy, a conqueror, or a visitor devoid of understanding.”

Patience and Norman’s friends in Carrara, the heart of Tuscany’s once thriving marble industry and where they had lived for five years, considered the move a “descent.” Even Patience, who would grow to love the wildness of the Mediterranean scrubland (the macchia) and the masseria’s solitary aspect, had her doubts. In a letter to her mother Olive, after a visit in 1968, she wrote, “Puglia is a very intoxicating place but probably altogether too remote to settle in. It really is the fin du monde.”

During the previous decade Patience and Norman had traveled throughout the Mediterranean, living on Naxos, in Catalonia, Carrara, and the Veneto, searching for a place to live and work. Honey from a Weed was the product of those travels and is as much a tribute to the people they befriended—peasants, farmers, and laborers—as it is a book of recipes. Indeed the recipes, often recounted as part of a larger narrative, are inseparable from the way of life that gave rise to and sustained them. It was this relationship that Patience sought to illuminate.

Patience at her desk. Photo by Stefan Buzás / courtesy of Nicolas Gray.

Patience at her desk. Photo by Stefan Buzás / courtesy of Nicolas Gray.

Ed Behr is not alone in his assessment of Patience’s work. Honey from a Weed has continued to captivate readers and, arguably, appeals to an even wider audience today than it did when it was first published. In the late 1990s Nigel Slater praised it in an essay on the art of recipe writing; a few years later April Bloomfield named it one of her favorite cookbooks; in 2016 Jeremy Lee, head chef of London’s Quo Vadis, described Honey from a Weed as “remarkably ahead of its time.” In the mid 1980s there were few people truly interested in foraging for edible plants or raising a pig and making their own coppa.

Much has changed since then, and the case Patience made for eating locally, observing seasonal rhythms, and growing one’s own food has become commonplace. Articles on foraging and wild foods, now de rigueur in such magazines as Food and Wine and Bon Appétit, have also appeared in mainstream nonculinary publications. In 2006 the New Yorker’s Bill Buford wrote about the pleasures and perils of butchering a pig in his New York City apartment. Urban gardens and rooftop farms are flourishing. Not surprisingly, some of the world’s top restaurants now devote significant resources both to foraging and to cultivating a bit of land. “Perhaps this very old approach is beginning once again to inspire those who cook in more complex urban situations,” Patience observed in Honey from a Weed. Indeed, her hope that a more traditional approach to food and cooking would take root, even amongst city dwellers, has exceeded the most optimistic expectations.

__________________________________

From Fasting and Feasting: The Life of Visionary Food Writer Patience Gray. Used with permission of Chelsea Green Publishing. Copyright © 2017 by Adam Federman. Now out in paperback.

Adam Federman

Adam Federman is a reporting fellow with the Investigative Fund of the Nation Institute covering energy and the environment. He has written for the Nation magazine, the Guardian, Columbia Journalism Review, Gastronomica, Petits Propos Culinaires, Earth Island Journal, Adirondack Life, and other publications. He has been a Russia Fulbright fellow, a Middlebury fellow in environmental journalism, and the recipient of a Polk grant for investigative reporting. A former line cook, bread baker, and pastry chef, he lives in Vermont.