The Literature of Migration and Caribbean Identity in America: A Reading List

Antonio Michael Downing Recommends Jamaica Kincaid, Canisia Lubrin, Edwidge Danticat and More

From Nicki Minaj to Rihanna, Neil de Grasse Tyson to Malcolm X, Carmelo Anthony to Kamala Harris, Caribbean migrants and their children have had a profound impact on not just Black American life but American life, period. Among the many cultural legacies of this longstanding conversation is what the great Bajan poet Kamau Brathwaite calls “the literature of migration.”

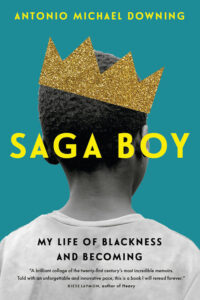

My memoir Saga Boy, My Life of Blackness and Becoming, can be viewed in this tradition. It’s my attempt to make sense of my personal experience. Yet, it also resonates on these universal migrant themes.

Here are some of my favorite books in this flavor. They are all different, but the central theme is, as I wrote in the introduction to Saga Boy, that they are stories about: “…unbelonging, about placelessness, about leaving everything behind. About being shattered over and over and reassembling yourself over continents and calamities.”

*

Audre Lorde, Zami

(Crossing)

Audre Lorde was, in her own words, a “Black, lesbian, mother, warrior poet.” Born in the Virgin Islands to a father from Barbados and a mother from Grenada, Lorde wrote Zami as a memoir of her early years in New York City and the formative experiences that brought her into living fully “out” as a queer person. What strikes me is not only the vibrancy of her prose but the power of her mythmaking; her sheer determination to draw the contours of her own life in a world where she did not recognize herself. Finally, her celebration of connections between women is triumphant—she writes, “Every woman I have ever loved has left her print upon me.”

David Chariandy, Brother

(Bloomsbury)

This novel is closely based on the author’s experiences growing up in Scarborough, a massive, mostly immigrant section of Toronto; my high school there educated students from at least 70 different nationalities! Brother introduces the complexities of growing up in this melting pot. Chariandy is a masterful stylist, he deftly navigates the stories of immigrant parents as they raise children who are disconnected from them. The parents have “useless foreign degrees” framed on the walls while their children, “oiled creatures of mongoose cunning,” bang hip-hop and kick it in barber shops seeking some sense of belonging. Brother is a celebration of brotherhood, a mediation on the divide between migrants and their children, and an exquisite book.

Jamaica Kincaid, An Autobiography of My Mother

(FSG)

“I’m someone who writes to save my life,” Jamaica Kincaid once said. I couldn’t relate more. Our stories are deeply stitched with similar themes: colonial callousness, potent Caribbean matriarchy, and migration to the promised land also known as America. The opening is straight fire: ”My mother died at the moment I was born, so for my whole life there was nothing standing between myself and eternity; at my back was always a bleak, black wind.” The sheer poetic, physicality of her world is heavy—the ripe fruit, the rain on the road, the sweat, and the blood—grabbing the reader with a sense of sensuality that doesn’t let go.

Edwidge Danticat, Brother I’m Dying

(Vintage)

Danticat is a master novelist, and this personal story of her family is riveting. Like Saga Boy, she addresses themes of migration, abandonment by parents, and attachment to a remaining relative (her father’s brother) to drive the narrative forward. She writes: “Exile isn’t for everyone. Someone has to stay behind, to receive the letters and greet the family members when they come back.” What becomes of those who stay and those who go? The old generation sacrifices for the new; she captures the sadness of this truth without being submerged by it.

Kamau Brathwaite, Trench Town Rock

(Lost Rocks)

It is hard to overstate how important Brathwaite is to Caribbean letters. His poetry captures the music and rhythm and texture of life in 70s Jamaica at the time that he and Bob Marley were living there. He uses punctuation, misspelled words, and Jamaican patois to communicate the danger of the postcolonial island collapsing into violence. “TWO SHATTS…with salaams & slams & semi-automatic acks, revolvers slung from belts and holsters or tucked like asps into their waist-line trousers; & evvabody walkin fass fass fass . . .

Canisia Lubrin, Voodoo Hypothesis

(Wolsak and Wynn)

This is a simply stunning poetry collection, rich in allusions, about migration, diaspora, and the evil effects of rampant capitalism on Black bodies. Lubrin hijacks the language of science, pop culture, and colonial poetic traditions to smash conventional ideas of Blackness. In “Give Us Fire Or The Black Prometheus,” she writes: “teething skin in the black guts / of slave ships, we’re through with being // you, or that Ulysses, figure: let us squall / with old Prometheus any day”

__________________________________

Saga Boy by Antonio Michael Downing is available now from Milkweed Press.

Antonio Michael Downing

Antonio Michael Downing is the author of Saga Boy. He grew up in southern Trinidad, northern Ontario, Brooklyn, and Kitchener. He is a musician, writer, and activist based in Toronto. His debut novel, Molasses, was published to critical acclaim. In 2017, he was named by the RBC Taylor Prize as one of Canada’s top emerging authors for nonfiction. He performs and composes music as John Orpheus.