Polly Adler’s literary adventures began the winter of 1923-1924. She was only twenty-three years old then and had not yet been crowned New York’s “Empress of Vice. ” But she’d come a long way since opening her first brothel in a two-bedroom apartment across from Columbia University in 1920. That winter, she was ready to make the next move in her career.

“I had always told my girls: If you have to be a prostitute, be a good one,” Polly said later. “Well, the same applied to me. If I had to be a madam, I’d be a good madam.”

Now, she declared, “I was determined to be the best goddam madam in all America.”

Her timing was ideal. Three years into the Noble Experiment of Prohibition, New Yorkers of all ages “had discovered that young liquor will take the place of young blood, and with a whoop the orgy began,” remembered F. Scott Fitzgerald. “A whole race going hedonistic, deciding on pleasure.”

In one of the most spectacular examples of the law of unintended consequences in American history, Prohibition gave the underworld a cachet it had never had before. The 18th Amendment to the Constitution banning the sale of “intoxicating liquors” had the perverse effect of transforming the sleazy underbelly of vice into a cutting-edge counterculture. “Slumming” had long been the hobby of sporting men, raffish intellectuals, and wealthy young rakes who had so much money and social stature that they could afford to flout conventional morality. Now anyone who wanted a glass of beer was forced to consort with criminals.

This inspired a delicious joie de vivre, at once noble and naughty, as writer Donald Ogden Stewart remembered nostalgically; it “made you feel that even in a teacup you were defying that damned Puritanical law, and consummating a rebellious act of independence and self-affirmation against the power of the reformers and their spies.”

By 1923, Polly Adler’s “speakeasy with a harem” had become a favorite oasis of the bootleggers and bookmakers eager to blow their ill-gotten gains. “Already my girls were known to be the best-looking, best-dressed and best—well, best all-around in New York,” she boasted. But she had higher ambitions: “What I really was shooting for was the patronage of the upper brackets of society, of theater people and artists and writers (the successful ones).”

So Polly set her sights on the Broadway bohemians known colloquially as the Algonquin Round Table. The nickname was in homage to the Algonquin Hotel, not far from Times Square, where their clique met for long, laughter-filled lunches, trading quips, plotting practical jokes, nipping from flasks, and inspiring envy in less lively diners.

Polly was strategic. The Round Tablers were professional wordsmiths and cultural influencers—the publicists, playwrights, and critics whose columns were must-read for the city’s sophisticates. They took the brash Broadway wisecrack, spiffed up its grammar, tossed in a few fifty-cent words, and turned it into fodder for glossy magazines and the legitimate stage. They were Rabelaisian modernists, the avant-garde in “the revolution in humor that seems to be taking place in New York,” as critic Edmund Wilson wrote in September of 1924.

To those who hadn’t felt the lash of their wit or the scorn of their criticism, their irreverent antics and public pursuit of fun were the essence of metropolitan sophistication. “The people they could not and would not stand were the bores, hypocrites, sentimentalists and the socially pretentious,” explained the novelist Edna Ferber. Insisting that they preferred an honest roughneck to a well-bred phony, they reveled in eloquent Irish bartenders and up-from-Second Avenue Jewish comics, and bought drinks for girls who hadn’t made it past the eighth grade but whose limpid eyes and flirtatious lines implied knowledge far beyond their years. They frequented shadowy speakeasies in Harlem and Greenwich Village, where gay life flourished and Blacks and whites mingled. Their late-night adventures fed the city’s gossipmongers—and drummed up business for the proprietors of their favored spots.

How Polly first enticed the Round Tablers to her establishment was never clear, for good reason. Those sorts of stories—no matter how often they were retold over drinks to gales of laughter—were rarely written down. But it was obvious why they kept coming back: the Broadway literati were, to use a new phrase of the era, sex-obsessed. Next to drinking, their favorite pastime was sexual adventuring, legitimated by the theories of Sigmund Freud and fueled by an endless stream of gin, rye, and whiskey.

Dorothy and Bob amused themselves by compiling a list of books for Polly to fill to her empty cases, including classics, current literature, and signed editions of her new friends’ books.One of the first to avail himself of Polly’s services was George S. Kaufman, the lead theater critic for the New York Times, who was beginning a meteoric career as a playwright and director of hit comedies. It was said, on good authority, that after his wife, the redoubtable Bea Kaufman, suffered a devastating miscarriage early in the 1920s, George lost all sexual desire for her. Not long after that, he found his way to Polly’s.

“He did not want to be seen at her ‘house,’ where he had a charge account,” remembered his friend Hudson Strode. Instead, George arranged for one of Polly’s girls to wait under a streetlamp on Central Park West. At the appointed time, the playwright would stroll up to her, make some small talk, then invite her to his pied-à-terre on West 73rd Street. Once finished, he ushered the girl out with an empty promise to meet again. No money passed between them; instead Polly presented him with a bill at the end of every month.

Polly welcomed Kaufman’s patronage, but his secrecy did nothing for her reputation. That changed when she met Robert Benchley. A Harvard man of old Yankee Protestant stock, Benchley radiated warmth. He had beaming blue eyes that creased behind a wide, toothy smile, and his bold, bellowing laugh was famous among theater audiences. He was married to the wife of his youth, who was tucked away with their two young sons in the quiet suburb of Scarsdale.

Like Kaufman, Benchley made his living being funny, as the charmingly flippant theater critic for Life magazine and a humorous essayist with several brisk-selling books to his name. In contrast to Kaufman, who specialized in the artful putdown and the lightning-quick wisecrack, Bench’s humor, while occasionally ribald, was gentle, self-deprecating, and had the effect of making everyone around him feel funnier than they actually were. “Robert Benchley was the kindest, warmest-hearted man in the world,” remembered Polly. “Petty, gratuitous meanness always infuriated him, and he despised snobs and hypocrites.”

When Prohibition began, Benchley was a dedicated teetotaler. Two years into the Great Parch, he decided to join the rest of the Round Tablers happily pickling themselves in bootleg gin. With the zeal of a convert, he developed the kind of bottomless thirst treasured by all liquor peddlers, with an “ability to drink all day and into the evening with not a hint of inebriation,” as one friend marveled.

In September 1923, Bench crossed over to the other side of the footlights when Irving Berlin hired him to deliver a comic monologue in Berlin’s Music Box Revue. It was an instant hit. His transformation from critic to star was even more fateful than that first cocktail. For the first time he was making $500 a week, big money for a writer. He went on a yearlong spree, spending every dime and then some on bootleggers, speakeasies, and skirts.

By the time Polly met him, Bob was the quintessential Broadway flaneur, who seemed to know every door tender in every speakeasy from Greenwich Village to Harlem. “There was an unholy joy,” said Donald Ogden Stewart, “in going down some steps to a dingy door, sliding back a panel and saying ‘I’m a friend of Bob Benchley’s—can I come in?’” The answer was always yes for a friend of Bench.

The fact that Robert Benchley was fast becoming one of Polly’s steadiest and highest-profile customers was soon an open secret among the fast Broadway crowd. “Let’s all go up to Pawly’s”—uttered in his Yankee accent—became his rallying cry. He was usually accompanied by a crew of boon companions, particularly his fellow humorists Dorothy Parker and Donald Ogden Stewart.

Don Stewart, who had already tasted the pleasures of prostitutes in his travels, was an eager convert to “Polly’s Follies”. Don, maintained his friend Scott Fitzgerald, “could turn a Sunday School picnic into a public holiday.” Dorothy Parker embodied the literary flapper; flippant, flirtatious, and risqué, peppering her conversation with witty wisecracks and clever put-downs. “She was ready for fun at any time when it came up, and it came up an awful lot in those days,” recalled Stewart. She was one of the few women who went toe to toe with the boys in writing, drinking, and screwing.

They would drop by Polly’s following a long lunch at the Algonquin, or after stumbling out of a joint that had the gall to close at three AM Dorothy and Polly would drink and chat while, in Don Stewart’s words, “I went upstairs to lay some lucky girl.” Dorothy and Bob amused themselves by compiling a list of books for Polly to fill to her empty cases, including classics, current literature, and signed editions of her new friends’ books.

When The New Yorker was founded in 1925, Benchley, Parker, and Stewart became frequent contributors, helping to set the irreverent tone of the magazine. Following Benchley’s lead, Polly’s house became a regular late-night rendezvous for many of the hard-partying staff members, including the managing editor Ralph Ingersoll, the art director Philip Wylie, writers James Thurber and Wolcott Gibbs, and Peter Arno, whose sly cartoons of flappers and sugar daddies became a signature of the magazine. Harold Ross, the founder and editor-in-chief was one of the few who failed to fall for Polly’s charms. Peter Arno once brought Ross to her bordello, remembered Wolcott Gibbs incredulously, but the editor brought along a stack of manuscripts “and just read them,” while the fun eddied around him.

Polly had never spent time with people like this before. “I didn’t even know the meaning of many of the words I was now hearing (and using!),” she recalled. “But I knew that my use and misuse of the new words I was picking up amused my customers, and many of them respected me for my eagerness to learn.”

They would drop by Polly’s following a long lunch at the Algonquin, or after stumbling out of a joint that had the gall to close at three AM Dorothy and Polly would drink and chat.Benchley and his friends were charmed by Polly’s untutored intelligence, warmth, and good humor. She cultivated a sly, self-deprecating wit, liberally sprinkled with comic malapropisms, and she expertly deployed the knowing wink, the subtle double entendre. “She spoke pure New Yorkese,” remembered the journalist Irving Drutman, a mélange of Yiddish inflection, Broadway timing, and burlesque innuendo. “When she escorted a client to the exit, she always said (in a slight accent), “Denk you. It’s all-vays a business doing pleasure mit you!” chuckled Walter Winchell.

In turn, Polly adored Benchley. “Of all the friends I made during my years as a madam, I think his was the friendship I valued most,” she wrote. “Bob lighted up my life like the sun, and sunny was the word for his whole nature.” Unlike most men of Polly’s acquaintance, he made no secret of his friendship and patronage, and he treated her girls with an endearing and authentic gentlemanliness that was rare in a brothel.

Bob’s friends sometimes struggled to reconcile his innate decency with his fondness for Polly’s services. Some insisted that “Benchley liked it because it never closed,” according to a biographer who interviewed many of his friends. “He could never go to bed—it was as simple as that.” Others attributed it to his topsy-turvy work ethic. “Benchley was a regular at Polly Adler’s not to partake of the available young ladies,” the critic Harold Stern insisted, “but simply because it was the one place in town which he could visit at any hour knowing he would always have a room and a typewriter at his disposal.” When pressed by a deadline, he’d often work at Polly’s until the piece was finished. But this sounds more like Pollyanna than Polly Adler.

As for Dorothy Parker and the other women in the Algonquin circle, they seemed to take the company of Polly’s professional seductresses in stride. But then, it would have been gauche to disapprove. “The 1920s had their moral principles,” as the critic Malcolm Cowley noted, “one of which was not to pass judgments on other people, especially if they were creative artists.”

But just beyond the madcap parties and carpe diem atmosphere, the sordid reality of life in a whorehouse was always lurking in the shadows. The boxer Jack Dempsey liked to tell a story he’d heard about the time Katharine Hepburn visited Polly’s house in the company of Bob, Dorothy, and the poet H. Phelps Putnam. It was the summer of 1928, and the twenty-one-year-old redhead was struggling to break onto the Broadway stage. Hepburn was shocked when Benchley suggested they head to “Pawly’s” for a nightcap. Ensconced in Polly’s parlor with a cocktail, she was starting to relax when first Benchley, then Putnam, disappeared in the direction of the bedrooms, and finally Parker excused herself to watch “an exhibition.”

When it was finally just the two of them, as Dempsey told it, the enterprising madam seized the chance to make her standard pitch to the aspiring ingenue. “Dorothy tells me you want to be an actress. That’s fine but it’s a hard life,” murmured Polly sympathetically. “There will be many times when you are hungry and broke and walking the streets wondering where your next meal is coming from. Don’t worry. Just come to Polly’s. I can always use a gal like you, although you’re a special type. Would you consider wearing a nurse’s uniform?”

_____________________________________________________________

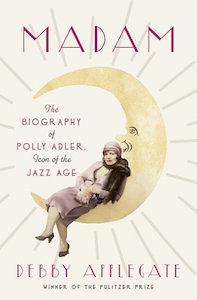

Debby Applegate’s Madam: The Biography of Polly Adler, Icon of the Jazz Age is available now via Doubleday.