The Limits of Pain: On Writing Against Chronic Illness

Ysabelle Cheung Considers How Her Experience With Endometriosis Has Shaped Her Short Fiction

At the start of Bora Chung’s short story “The Head,” a strange creature emerges from the toilet bowl. Resembling “a lump of carelessly slapped-together yellow and gray clay,” it rises from the water and speaks. Mother. The protagonist flushes it immediately.

Yet it returns. Each time the protagonist enters the bathroom, it is there. Soon we realize what it is actually made of: feces, urine, menstrual blood, and hair. All the rejected discards of a woman’s body, clumped together in a new sentient form.

I read Chung’s short story a few years ago while I was working on my short story collection, Patchwork Dolls. As with all stories I tend to love, my instinctual reactions of disgust, paranoia, and fear dissolved into a strange catharsis. I felt an acknowledgement of my own complicated, abject relationship with the body I live in and its mechanics of waste and pain, rendered through Chung’s imagined creature. Wavering between empathy and revulsion, I read the story again and again in the lead up to the publication of my own collection. I was trying, and failing, to understand my own body; trying, and failing, to understand the limits of pain.

*

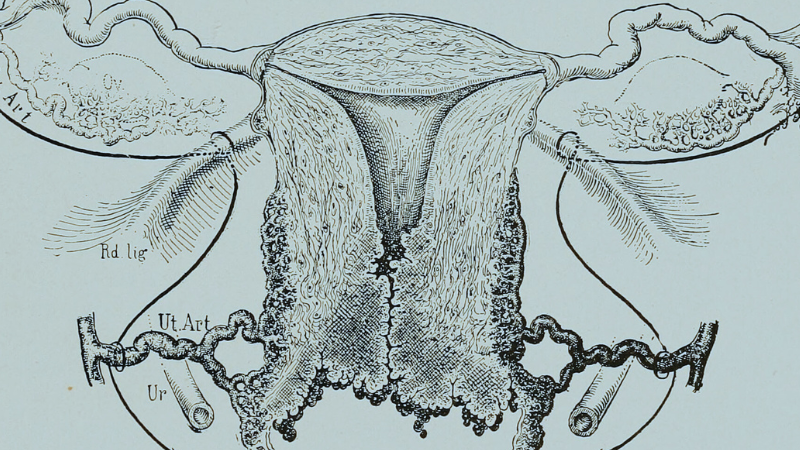

Endometriosis is a chronic condition in which extra endometrial tissue grows inside and outside of the uterus lining. During a period, when the lining is typically shed, this extra tissue also responds—thickening, cramping, bleeding, and eventually, scarring. Every cycle, the mass grows, tears and bleeds again. Women have reported endometrial growths in their ovaries, pelvis, even intestines, kidneys, and the brain, where the tissue spreads and attaches itself to the organs, obstructing their function.

To link something together is to acknowledge that disparate parts are from the same source, that there is an undeniable connection between them.

According to the World Health Organization, endometriosis affects 10% of individuals who menstruate. There is no cure, and its cause is unknown. You cannot die from this, although the pain reconstitutes you, reforms you into an unfamiliar version of yourself.

I am one of the luckier ones. The recurring cysts, polyps and endometrial growths inside my ovaries and uterus are removable, via invasive surgery, and I am fortunate enough to work according to my own schedule, with the support of an extraordinarily understanding partner.

Still, a day’s plan can be wrenched out of place by an unexpected incident. Last week, I had planned to meet up with a dear friend to deliver her an early copy of Patchwork Dolls. I arrived at our restaurant reservation in some pain. I took two Advil, some hot water. The pain increased. I did not get better. My partner ran to collect and deliver me to a soft space where I could lie down.

The word for pain has its roots in Latin, where the poetic-sounding poena translates loosely as punishment, or penalty. It is difficult to consider pain as objective when the word itself is related to the consequence of an action, an invisible deed you did or did not do. The Ancient Greeks used to believe that some women possessed “wandering wombs”—displaced uteruses that travelled around bodies like birds—as a direct result of that body failing to reproduce. Plato wrote: “the animal within them is desirous of procreating children, and when remaining unfruitful long beyond its proper time, gets discontented and angry, and wandering in every direction through the body, closes up the passages of the breath, and, by obstructing respiration, drives them to extremity, causing all varieties of disease.”

This horrifically inaccurate and misogynistic description encapsulates the main societal issue with pain related to a woman’s sex organs: that the world has historically denied, and still cannot imagine, women’s bodies without babies. Because of this, medical research into endometriosis is poorly funded and for a long time, deemed unnecessary. In the English-speaking part of the world, some movement has been made in a positive direction—electronic health records are now being studied to consider the presence of comorbidities in relation to endometriosis—but the majority of people still have not even heard of this condition, and as a result women are left undiagnosed for years.

Whenever I wander onto Facebook these days, I come across posts from a group I joined long ago for people with endometriosis. I can’t bring myself to leave the group, but truthfully I find the posts too dark. Most of them are women asking if it gets better, to which the answer is always no. Some of them share links about early research but are shut down by others who state that they have vastly different symptoms, expressing just how wide-ranging the condition is. The most triggering posts for me, however, are the ones in which someone has given up, after years of surgeries, medications, and reduced quality of life. Their partners don’t recognize them anymore, won’t touch their bodies, and the pain is all they can think about. In these posts, they ask if there is a place where they can be legally euthanized.

*

Before I started working on my collection in earnest, I was told that my stories would be looked on favorably if they were linked. Articulating that continuity was the job of the writer. Some, like Brandon Taylor, include the same characters across story arcs; others such as Carmen Maria Machado rely on the mechanisms of the uncanny to carry the reader through to the very end. When thinking of what links my ten stories together, I realized that themes of disappearance and reappearance had quite organically embedded themselves in the texts. This was not deliberate, but it conveyed something about my state of mind as I wrote them, under stress from the constant changing regulations of my home city, grappling with understanding my role as a young Asian woman in the world.

The truth of writing the ten stories in my collection, however, is that I wrote them from different parts of myself.

To link something together is to acknowledge that disparate parts are from the same source, that there is an undeniable connection between them. Sausages are linked, for example, via a long tubular casing that holds pink meat from the same animal. The truth of writing the ten stories in my collection, however, is that I wrote them from different parts of myself—sometimes well, sometimes very unwell—and my memory of how I wrote and revised them also changes depending on the level of pain that day. When lucid, I can happily write for hours. But in an episode of illness, words leave me suddenly; I can barely recall how sentences work, let alone how to formulate stories, characters, and futures. My mind disappears, in its place my heavy body and its alien growths. This is why in my stories I obsess over begin-again duplicates and resurrections: robot clones, ghosts, sentient fungi.

To mitigate this disembodiment, I inserted a hidden link in my stories. This link takes the form of a repeated character who appears in different timelines and via different genders: Doctor Wong. To me, Dr. Wong is neither malicious nor benevolent, but rather a neutral character, an earthly link that reminds me of the realities of our rigid medical industry and normative society. Dr. Wong possesses information about this hostile world and delivers it to the characters, who take what they are given, confront it, and figure out how to survive.

Tabe Mitsuko, “Artificial Placenta,” 1961/2004, collection of Contemporary Art Museum, Kumamoto, installation view of “For a Placard”, The National Museum of Art, Osaka, 2025-2026./Yamanaka Shintaro (Qsyum!)

Tabe Mitsuko, “Artificial Placenta,” 1961/2004, collection of Contemporary Art Museum, Kumamoto, installation view of “For a Placard”, The National Museum of Art, Osaka, 2025-2026./Yamanaka Shintaro (Qsyum!)

In early January, I saw an installation by Japanese female artist Tabe Mitsuko at the National Museum of Osaka. The installation was about the imagined liberation from procreation, and the fraught, often violent relationship between a woman’s mind and body. It comprised three white wombs, fashioned out of a cotton-like fabric, soft and fluffy. This pleasant appearance aggressively contrasted with a series of red-painted nails driven into the surfaces and hollowed-out interiors, at each center a radio vacuum tube and black light bulb. The placard underneath the sculptures read “Artificial Placenta,” and the date “1961/reworked in 2004.” She had made the sculptures when she was pregnant but had destroyed them very shortly after exhibiting. The work I was looking at now was a recreation, its very physical presence a symbol of destruction and pain, growth and fear.

In the quiet of the museum, the installation stared at me: the tiny scarlet nails like tiny eyes, the black light bulb reflecting my own face to me.

I stared back at it.

__________________________________

Patchwork Dolls by Ysabelle Cheung is available from Blair.

Ysabelle Cheung

Ysabelle Cheung is a writer and art critic based in Hong Kong. Her fiction writing has appeared in Granta, Catapult, Slate, and the Rumpus. Her short story "Please, Get Out and Dance," published in The Margins (AAWW), was nominated for the 2022 Pushcart Prize. She was awarded the 2023 Diverse Writers Grant by Speculative Literature Foundation; the 2023 Aspen Words fellowship; and the 2021 Nebula Awards SFWA conference scholarship. She is an alumni of Tin House Workshop and was in residence at the Jan Michalski Foundation in 2024. Her essays and cultural criticism have appeared in the Atlantic, the Los Angeles Review of Books, Artforum, Frieze, and LitHub. In 2022, she co-founded the contemporary art gallery Property Holdings Development Group.