The Life of Carla Capponi, Nazi-Fighter of Occupied Rome

"Heedless of the flames, she pulled the injured soldier from the burning wreck."

With Teutonic precision, Ordnungspolizei (Order Police) Sergeant, 33-year-old Georg Johansen Schmidt, every evening at 6 pm, belted his black leather dispatch case closed and exited the Hotel Ambasciatori on Via Veneto. Although carrying highly classified documents, he was unescorted as he was in the secure and closely guarded German Headquarters Zone where senior Wehrmacht officers worked and lived in Via Vittorio Veneto’s luxury five-star hotels.

And so, on the evening of December 17th, 1943, Schmidt, in his black police uniform and carrying his dispatch case, was easily recognized by the woman discretely shadowing him. Carla Capponi was an attractive, petite, fair-haired, 21-year-old university of Rome student employed as a secretary who lived with her mother in a large apartment that overlooked Trajan’s Column. She dressed elegantly, never leaving home without gloves.

A Florentine, Capponi was descended from nobility on her father’s side. Her great grandmother was Viennese, Jewish, and a marchioness, but after her father died, the family fell on hard times. Expensive artwork, Etruscan vases and some of their once elegant furnishings were sold off for food and rent.

Capponi watched Schmidt near the shuttered American Embassy, the Palazzo Margarita on Via Veneto. As an elegantly turned out young woman she looked like other women killing time along the street, waiting to meet German officers. She however was not alone; her Partisan boyfriend, Rosario Bentivegna, a third-year university medical student, was hidden in a side street where he could watch Capponi.

Unaware that he was under observation, Schmidt left the hotel, turned right and walked half a block down Via Veneto. In front of the closed embassy, he crossed the street where Via XXIII Marzo entered Via Veneto. He was on his way to Via Venti Settembre and the Italian Ministry of War, now occupied as a command center by the German Wehrmacht.

Schmidt walked briskly down the street for two blocks to the intersection of Via San Nicola da Tolentino. Suddenly from ten meters, two shots echoed off the grey buildings. Capponi had fired a brand-new Beretta 9mm pistol she had earlier lifted from a Fascist soldier’s holster on a tram. Schmidt fell in the southwest corner of the intersection; dying he cried: Mein Gott! Ich sterbe! Helft mir (my God, I’m dying, help me.)

Capponi heard the screams of a tanker trapped inside the Italian tank. Heedless of the flames, she pulled the injured soldier from the burning wreck.

Ignoring him, Capponi grabbed the dispatch case which held maps marked with the location of anti-aircraft batteries surrounding Rome and fled. The information was sent to the Allies in the south via an Italian Military Clandestine Intelligence organization in Rome.

*

Carla Capponi became a Partisan shortly after the Nazi occupation of Rome on September 10th, 1943. Clandestinely, she listened nightly to the BBC and during the early evening of September 8th, 1943, heard US General Eisenhower broadcast the news that Italy had signed an armistice with the Allies. Italy was out of the war. Like the rest of Rome, Capponi was thrilled at the news, but was uncertain what would happen next. The answer came early the next morning: German troops invaded Rome.

As dawn broke, inadequate Italian forces to the west of the city resisted the German advance. Outnumbered, Italian troops fell back and streamed past the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls along the Ostia Road. Arriving at the Porta San Paolo, the ancient gate in the Aurelian wall at a first century BC white marble pyramid tomb they stopped. German troops were fast on their heels.

Hearing the call from the street for volunteers, Capponi announced that she was going to fight the Germans. Her mother, horrified, forbade her to go, but the headstrong young woman dashed out the door and raced to Porta San Paolo; toward the sound of the guns.

By the time she arrived, the fighting was already fierce; stray bullets scaring the white marble pyramid. Capponi had no military experience but she helped strengthen the barricade and joined other women caring for the many wounded. Seeing that the situation was hopeless, the Italian defenders abandoned the gate. Capponi fell back to the broad expanse of the Ancient Circus Maximus.

Next she heard a great rumble and mechanical clanking, a 62-ton Wehrmacht Tiger I Panzer moved along the cobblestones from the Pyramid towards the Colosseum. At the circus, the panzer blew up one of the few remaining Italian mobile light tanks sent to stop the Germans.

Capponi heard the screams of a tanker trapped inside the Italian tank. Heedless of the flames, she pulled the injured soldier from the burning wreck. Half carrying him from the scene she made for the 4th-century Arch of Constantine, pursued by the panzer which fired its 88mm gun into the piazza, barely missing the Colosseum.

Capponi dragged the wounded soldier up the small hill to the ruins of the temple of Venus and Rome. Later she wrote that she couldn’t help thinking that she was in the middle of a battle taking place in a museum surrounded by two thousand years old monuments.

From there she headed down Via dei Fori Imperiali to her apartment. With the help of the portiere, she dragged the injured man up the steps to the apartment. Her mother, overjoyed that her daughter was still alive, welcomed the wounded man into her home. On the street below, Italian soldiers flooded past, discarding their uniforms as they went. Capponi emptied out her late father’s closet and dropped civilian clothes to the fleeing soldiers until she had no more left.

*

Shortly thereafter, Carla Capponi met medical student Rosario Bentivegna when he delivered documents to her apartment for a clandestine meeting of the budding Partisan movement. Capponi and Bentivegna became a powerful team and eventually became lovers. The two joined a Communist Partisan organization called the Patriotic Action Groups (GAP) in October 1943.

Carla Capponi, as a result of her Partisan activities, remained in poor health for the rest of her life.

GAP leaders were often Rome University professors and intellectuals and their members were idealistic middle-class students. GAPs pledged to carry out urban guerilla warfare to assassinate German and Fascists officials; attack military headquarters and moving columns of troops; destroy radio stations, railway hubs and war materiel.

As November turned to December, the Partisans increased their attacks on the Nazi occupiers, launching seven attacks in rapid succession. Capponi and Bentivegna and others threw pipe bombs into a German frequented trattoria; blew up trucks in front of the Opera House; killed soldiers as they exited the screening of a German language film at the Cinema Barberini; attacked guards at Rome’s central prison; and other actions.

The GESTAPO, using their vast network of informers, identified members of the GAP and arrests started. Nevertheless Capponi was a key participant in the most spectacular Rome Partisan attack on March 23rd, 1943 where more than 33 German policemen were killed in a daring daytime bomb attack. This time the Nazis retaliated with the worst wartime reprisal in Rome. At the Ardeatine Caves just outside of the Appian Way city gate, 335 men and boys were murdered.

Carla Capponi, as a result of her Partisan activities, remained in poor health for the rest of her life. After the war she became a successful journalist and later served in the Italian Parliament as a representative of the Italian Communist Party (PCI). She was presented a gold medal by the Italian Government. Bentivegna and Capponi married and had a daughter Elena, Carla’s Partisan codename, but divorced in 1974.

She died November 24th, 2000 and her ex-husband, Bentivegna, died on April 2nd, 2012. Today marks Carla’s twentieth anniversary of her death.

*

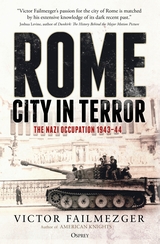

The city is the central character of Rome, City in Terror, the Nazi Occupation of Rome (1943-1944) (Osprey Press, Oxford, UK September 2020). It is a history of the nine-month-long German occupation of the city. The Gestapo wasted no time putting an iron grip on the city and rounded up thousands of Romans to build extensive defensive lines across Italy. And, at 5 am one morning, they arrested more than 1,000 Roman Jews and sent them to Auschwitz.

The book tells the story of the Allies, clergy, diplomats, civilians, Germans, Italians, Partisans and spies. Many operated out of the Vatican, under the very nose of the Pope. They formed a nationwide organization called the “Escape Line” and more than 4,000 Allied POWs scattered all over Italy were sheltered, clothed and fed by these courageous individuals whose lives were forfeit if their activities were discovered.

__________________________________

Victor Failmezger’s Rome –City in Terror: The Nazi Occupation, 1943-44 is now available.

Victor Failmezger

Victor Failmezger, the author of Rome, City in Terror, is a retired naval officer and in the early 1980s served as the Assistant US Naval Attaché in Rome.