The Life-Changing Magic of 10 Things I Hate About You

Or: Whence the Border Between Preference and Personality?

1. Kat

Twenty years ago this week, 10 Things I Hate About You hit the big screen. A reimagining of Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew, but set in high school (because it was 1999), it opened at #2 in the US, just behind The Matrix. (Yes, yes, we’re all super old.) It also changed my life. When I tell people this, they usually laugh, as though that’s embarrassing, or a lie.

I grew up in a house with one small TV. It was in my parents’ bedroom, and I was allowed to watch Saturday morning cartoons for a single hour a week. I do not remember experiencing this as a hardship at the time—it’s not as though that television had cable, even, and anyway I liked to read. Eventually, we did get a second, equally small TV, with a built-in VHS player, which my parents abandoned downstairs in the living room, unnoticed by our couches, which continued to have eyes only for each other. The only thing I ever remember watching on the second TV is Bob Ross and static. Oh, and movies.

I was twelve in March of 1999, when 10 Things I Hate About You came out, though I didn’t see it in theaters. I saw it only months later, on that second small TV, and I remember being weirdly entranced by the white and green VHS box, with the six main characters[1] on the front, and the little arrow descending from the final ‘u’ of the title to point, oddly, at Bianca’s clavicle, somewhat missing its target of Patrick, who is object of the titular hate. (Misdirection, Kat might call this.)

So: by now I’m thirteen. I sit on the rug in front of the television. The Barenaked Ladies’ “One Week” plays over those colorful chalk-scratch credits. I know this song. It’s what I would later learn is called “non-diegetic sound”: sound not existing in the world of the movie, but only for the viewer. Except that it isn’t, because presently, a car full of lip-glossed bubblegum poppers rolls to a stop at an intersection, and we see that the music is in fact coming from their car. They’re bopping to the beat, singing along.

Up pulls Kat Stratford—the mewling, rampallian wretch herself—in her rusted red beater. Her Joan Jett drowns out their Barenaked Ladies. They sneak a glance in her direction; their eyes immediately return to the road/camera in fear. The expression on Julia Stiles’s face is perfect in its neutrality. She drives off, and the credits continue, and the music is non-diegetic again—but now it’s Joan Jett. Kat has hijacked this movie. This movie will now proceed on Kat’s terms. Kat, who doesn’t fit in. Kat, who doesn’t care what anyone thinks of her. Kat, who does not wear lip gloss, or bop. On the rug, I sit up straight.

2. Sylvia

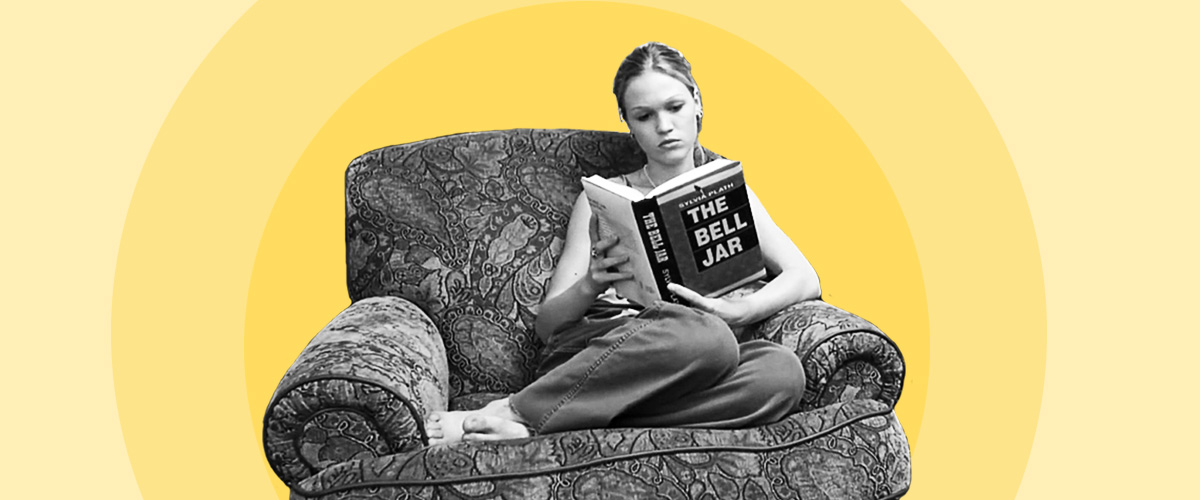

Despite the fact that all princesses know kung-fu now, at the time I had never seen anyone like Kat Stratford on television: a lead female character who drove a cool car, extolled the virtues of feminist literature, once kicked Bobby Ridgeway in the balls (unless in fact he did he kick himself in the balls, right after groping her in the lunch line), used words like “sphincter,” played the guitar, and—importantly—sat around after school reading The Bell Jar. “Make anyone cry today?” her father asks when he comes home to find his daughter curled up with Plath. “Sadly, no,” she says, barely looking up from her book. “But it’s only four-thirty.” Her father, Walter, beams[2]. At thirteen, I was shocked by this girl. And I decided I definitely wanted to be her.

So I bought a copy of The Bell Jar. I asked my parents for a guitar (I played the harp at this time, which is neither here nor there). I adopted what is turning out to be a lifetime aversion to Ernest Hemingway (“an abusive, alcoholic misogynist who squandered half of his life hanging around Picasso trying to nail his leftovers”). I started going to punk and hardcore shows at my local community center. My high school had a dress code, so instead of wearing long-sleeved crop tops and cargo pants to class, I began to wear knee-high black boots every day under my khakis (cool, I know). More crucially, I began to express my opinions—freely, loudly—even when they were unpopular, or worse, unladylike. I entered what my father once called “the cult of witty remarks.” When I myself was groped, my breasts grabbed not in the lunch line but in front of the school, by the flagpole, I didn’t kick the groper in the balls—but I did hit him in the face so hard he cried.

Violent tendencies aside, the most important part of all of this was The Bell Jar. After all, it is a known fact that Sylvia Plath, applied at the correct time, can change everything. I had always been a reader, but I had mostly been a reader of the books my dad liked—lots of 1970s sci fi and fantasy—plus random things I found around the house. The Bell Jar was the first book I sought out, and the first book I felt ownership of, because I had discovered it for myself. It was the first book I ever read that felt like high art to me, and the first book I ever read that made me want to write one. It felt like a key to a lock I didn’t know I possessed.

Not only that, but suddenly I associated reading with something other than entertainment: suddenly it was a signifier of a certain way of being, a sense of self that I coveted. Suddenly, liking to read didn’t make me a nerd. It made me a rebel—a rebel who was probably going to make somebody cry later, and therefore be insulated from crying herself.

Twenty years later, my life revolves around literature. I write about books for a living; I have a novel coming out next year. I think of myself as a writer, but primarily as a reader. Would this have happened without 10 Things I Hate About You, or without that one scene where Kat reads The Bell Jar? Maybe. Maybe even probably. But as a turning point in my self-conception, I could have done worse.

3. Mandella

All of which is to say that Kat made an outsize impression on me, as she was meant to. But there’s also Mandella. In case you don’t remember Mandella, she is Kat’s best (only) friend, played by Susan May Pratt. She loves William Shakespeare. Like, really loves him.

Mandella has about three minutes of screen time in the entire film. That’s enough, I guess, because she only really has that one characteristic: being obsessed with Shakespeare. As it stands, it’s not much to go on, but for me she had immediate appeal. Let’s put it this way: I had grown up watching an animated version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and as a child, my parents used to trot me out at the end of dinner parties so I could entertain them with a recitation of Puck’s final soliloquy from A Midsummer Night’s Dream (“If we shadows have offended / think but this and all is mended,” etc.). None of my friends had any idea what I was talking about when I tried it on them. But Mandella would have. Regardless, I liked that she was a reader; no one I knew outside my family really was. I loved that she was obsessed with something. I thought that meant she knew something I didn’t.

This is a story I rarely tell: I glimpsed her once, when I was visiting colleges my senior year. I got to sit in on a Shakespeare class in a beautiful gray stone building, and I kid you not, there was a weird dark-haired girl in there, perched bird-like on the edge of her chair, with a velvet jacket and a braid hanging in her face and her hand held up as high as it would go. I couldn’t see her whole face; I can only assume it was Mandella. I ended up choosing that school, but I never saw her again on campus. It’s always possible I hallucinated her—but that doesn’t change the fact that I followed a fictional character to college.

4. Your Big Dumb Combat Boots

10 Things I Hate About You not only changed the way I read, but it also changed the way I dressed. After all, this movie, which had become my bible, is deeply invested in what everyone is wearing, or would be wearing, or should be wearing—beginning with Bianca and her “strategically planned sundress.”

See also: “There’s a difference between like and love,” Bianca assures Chastity. “I like my Sketchers, but I love my Prada backpack.”

See also: “Your little Rambo look is out, Kat,” Joey “Eat-Me” Donner sneers from his cherry red convertible. “Didn’t you read last month’s Cosmo?”[3]

See also: “You don’t buy black lingerie unless you want someone to see it,” Bianca informs Cameron. But no, he certainly cannot see her room.

See also: “So, then Bianca says that I was right,” Cameron jibbers to Michael as they get ready together for Bogie’s party. “That she didn’t wear the Kenneth Coles with that dress because she thought it was mixing genres. Right? And the fact that I noticed—and this is a direct quote—really meant something.”

“You told me that part already,” Michael says. “Stop being so self-involved for one minute. How do I look?”

And well, let’s not forget the belly. No, not the yards of midriff that everyone[4] shows—most notably between the cheap fabric of Bianca’s terrible, terrible prom dress, what was she thinking—but The Belly, which Bianca and Kat’s father makes the former wear before Bogie’s party. “Just around the living room for a minute so you can understand the full weight of your decisions.” Bianca holds out her arms passively for an enormous pregnancy jacket. “Every time you even think about kissing a boy,” says Walter, “I want you to picture wearing this under your halter top.”

While it’s not surprising for a movie about high school to have a vested (sorry) interest in clothes, much of this originates in the original Shakespeare. Here I will make use of my degree in English literature to remind you that in the play’s frame narrative, Christopher Sly is a tinker passed out on the street when a bored aristocrat comes upon him and decides to dress him up and tell him that he’s a rich lord who’s merely had a bout of “strange lunacy.” With a few silks, rings, and a nice bed, they convince Sly that his whole life until that moment has been mere hallucination. It doesn’t take long for him to completely renounce himself.

Am I a lord? and have I such a lady?

Or do I dream? or have I dream’d till now?

I do not sleep: I see, I hear, I speak;

I smell sweet savours and I feel soft things:

Upon my life, I am a lord indeed

And not a tinker nor Christophero Sly.

Well, bring our lady hither to our sight;

And once again, a pot o’ the smallest ale.

Now, as Mr. Morgan would say: I know Shakespeare’s a dead white guy, but he knows his shit. Both play and rom-com implicitly argue that clothes make the (wo)man—that is, that our very identities are changeable, as changeable as our outfits, and even dependent on them. Hence those knee-high black boots that I began to wear, which had the added value of making me taller than all the boys in my class.

5. First, Are You Our Sort of a Person?

But clothes are only the most obvious indicator of what 10 Things I Hate About You suggests about who we are, and why.

Patrick is selected to seduce Kat because of his perceived counterculture-ness. That is, he’s the only person Michael and Cameron can think of who might not be afraid of her. (“I heard he ate a live duck once.”) After all, he wears black and has an accent and hangs out with that kid with a Mohawk, so sure. (“Everything but the beak and feet.”) He’s “tough” and Kat is “tough” so, perfect match, right?

For a romantic comedy, sure. Eventually we see different sides of Patrick; not so Mandella, who (as you may remember) only has that one quality. Even her clothes seem to be chosen only to reflect “girl who likes Shakespeare” (remember the snood). Narratively speaking, it’s fine that Mandella is mostly a receptacle for what would otherwise be Kat’s monologues about prom[5]. But what is particularly interesting to me about Mandella is the specific nature of her flatness—that is, the fact that her entire character consists of a single preference. She’s a marketer’s dream; she’d buy anything with the bard slapped on it. Now, I see her as representative of a pressing delusion among Americans: that it’s what we like—particularly if we like it to the point of obsession, which we are constantly encouraged to do[6]—that makes us who we are. That is, that it’s not our personalities that inform our preferences, but our preferences that create our personalities. We define ourselves by our interests, our likes (long walks on the beach, etc.) and dislikes, our particular fandoms, our political preferences (though this is a big dirty can of worms I won’t touch here), and our clothing choices. Black boots, etc. Even—gasp—books.

This, of course, is exactly what I did at twelve when I decided to become more like Kat. I thought if I dressed and acted tough, I would become tough. I thought if I read Plath, I would become the kind of person who read Plath. The difficulty, of course, is that it worked.

Not unrelated: the opening of Sylvia Plath’s “The Applicant,” which I read shortly after The Bell Jar and which is still my favorite poem of hers:

First, are you our sort of a person?

Do you wear

A glass eye, false teeth or a crutch,

A brace or a hook,

Rubber breasts or a rubber crotch,

Stitches to show something’s missing? No, no? Then

How can we give you a thing?

6. Your Basic Beautiful People

But why are we so eager to define ourselves at all, by our interests or anything else? Well, to sum up centuries of philosophical inquiry: the unknown is terrifying! We want to know what we are because it’s the only way we can know where we belong. Which, in high school, means cliques. 10 Things has a particularly splendid version of the traditional lunchroom clique breakdown scene—they have not only “your basic beautiful people” (“unless they talk to you first, don’t bother”), White Rastas, and future MBAs (“Yuppie greed is back, my friend”), but also cowboys (“the closest they’ve come to a cow is McDonald’s”) and coffee kids (“That was Costa Rican, butthead!”). There is something instantly comforting about this scene, both because of its ubiquity[7] and because—well, it feels good to be sorted. It feels like the proper order of things. A place for everything and everything in its place.

I’m not saying that there’s anything necessarily wrong with this, though it feels limiting. And again we come to one of the essential tensions of the movie (and the play (and our existence?)): the contrast between the accepted truth of the assigned persona, and the emptiness of same. 10 Things I Hate About You is all about clashing sets of identity, but it also acknowledges those identities as constructs, as performances, without undermining their contextual importance. Judith Butler would be proud.

Think about this: every romantic coupling in this film is directly brought about by the man taking on the preferences of the woman in some way, so as to win her—or so as to be a better match for her, as if preferences were what made people click. Patrick does this to get Kat—after Cameron searches her room for clues (“Likes: Thai food, feminist prose, angry girl music of the indie-rock persuasion”), Patrick shows up at Club Skunk[8] to name drop her favorite bands to her. Cameron “learns French” so he can tutor Bianca, and Michael goes so far as to pretend to actually be William Shakespeare because he knows that’s what Mandella likes. (How does he do this? Let me give you a hint: clothes are involved.)

Or think about this: everyone in this movie is constantly defining one another, especially Kat. Bianca knows exactly who Kat is. (“Has the fact that you’re completely psycho managed to escape your attention?”) Patrick knows who Kat is. (“You’re not as mean as you think you are, you know that?”) Walter knows who Kat is. (“You’re eighteen. You don’t know what you want.”) Joey knows who Kat is. (“As opposed to a bitter, self-righteous hag who has no friends?) Even Miss Perky knows who Kat is. (“‘Heinous bitch’ is the term used most often.”)[9] Mandella is the only one not trying to define Kat to Kat. Maybe that’s why they’re friends.

7. William S.

As it turns out, Mandella’s love of Shakespeare is something more than just a preference—and maybe even something more than an obsession. When Michael, campaigning on Patrick’s behalf, comes to talk to Mandella, who is mildly more approachable than Kat, he tells her he knows she’s a fan of Shakespeare. “More than a fan,” she says, stern. “We’re involved.” Later on, when Mandella is left without a prom date (and, apparently, a dress—so much to unpack, clothing-wise), she opens her locker to find a vaguely Renaissance-y gown and a note, which reads: “O Fair One. Join me at the Prom. I will be waiting. Love, William S.” At said prom, when Mandella runs up to Kat to ask her if she’s seen “William,” who told her to meet him there, Kat is disturbed. “Oh, Mandella,” she says. “Tell me you haven’t progressed to full-on hallucinations.”

How seriously are we meant to take this? Setting aside the fact that it’s absurd to suggest Kat and Mandella haven’t talked yet about her date for prom—and the fact that he bought (made?) her a dress in the correct size because he somehow knew she “didn’t have one,” and wait, how did he get it into her locker, especially without Kat’s help—this is probably the most interesting idea in the whole movie, even if it’s not fully fleshed-out: that there’s a teenage girl in this fancy high school who truly believes she’s in a relationship with William Shakespeare, and that he’s taking her to the prom.

Maybe the reason this detail is so alluring, without being really satisfying, is that Mandella’s hint of delusion is actually a vestige of a previous version of the character, one who wasn’t quite so singular in interest and purpose—and one who had more lines. “Mandella was a really dark character in the first few incarnations of the script,” Pratt told BuzzFeed News. “She was very much trying to kill herself so she could join Shakespeare in heaven.” She even scratched at her wrists with the sharp parts of a spiral-bound notebook, a scene I can’t imagine fitting into the movie as it stands. “There was also this scene—You know Isadora Duncan?” Pratt said. “She was a dancer and she was in a convertible and she flung her scarf around her neck and it got wrapped around the wheel and she was decapitated. Well, Mandella would do weird things like that. She’d get into a convertible and fling her scarf around her neck or dangle it off the side.” All of that got cut, obviously, and the movie is probably better for it—it’s a bit on the nose. But it hints at something quite compelling: a character so obsessed with a literary figure (who is possibly a construction, by the way, don’t tell Mandella) that she wishes her own death so she might meet him—an even more extreme version of the preference-as-personality syndrome. It’s not just preference as personality, it’s preference as life or death.[10]

8. The Marriage Plot

In the end, it’s Michael who has invited Mandella to the prom, and Michael who is dressed up as Shakespeare waiting for her there. I mean, of course it is. This is ultimately an adaptation of a marriage plot, after all. For Shakespeare, there were really only two ways to end a play: with everyone married, or with everyone dead. The marriage plot, in literature and film, is exactly what it sounds like: the plot begins with desire, hinges on the ups and downs of courtship, and ends when 2 become 1. It necessarily supposes that a happy ending is a married one (lol), and the whole course of events advances towards that goal. Jane Austen, Flaubert, the Brontës. They all did it. Francine Prose once put it this way in the New York Times: “as we may dimly recall learning in high school, marriage is a metaphor for order and harmony restored, for the broken, disrupted world mended and made right. . . We want to believe in enduring love partly because we know that we will always be subject to, and at the mercy of, the pendulum swing between chaos and cohesion, happiness and heartbreak.” Fair enough, I guess—though that pendulum swing sounds a lot like modern marriage to me.

So in the end, when Kat has been paired with Patrick, and Bianca with Cameron, there’s nothing left but to find suitors for their minor best friends. The bad one, Chastity, gets the bad one, Joey, and the good one, Mandella, gets the good one, Michael. The guy with the Mohawk is, alas, left unmatched. Chastity and Joey make sense; they’re both evil beautiful people, but Mandella and Michael? She’s so far out of his league it’s embarrassing. (Though not, of course, in the logic of the movie, where both of them are outside clique and therefore they should take whatever they can get.) But hey, I guess what we’ve learned is that if you put on a ruffle, memorize a couple of lines and call yourself William, the Shakespeare girl will go out with you.

Unfortunately, I can’t condemn any of this, because I instantly started dating the first boy I found who also liked poetry. And in the end, this is what growing up is all about: finding ways to identify yourself, using the only thing you have—the world—as mirror or antagonist or something in between. If it’s books or clothes instead of drugs or violence that you use for self-definition, so much the better. And it never really goes away. At the beginning of our courtship, my fiancé and I sent each other poem after poem. We sat down and exchanged our favorite novels. We both loved what the other sent. Maybe we would still have fallen in love if we didn’t. But you know what? I kind of doubt it.

[1] Sort of—what about Michael and Mandella?

[2] Later, due in large part to Kat’s influence, I would see this exact smile transplanted onto my own father’s face, when he saw me draw blood and get red carded out of a soccer game. “It’s not every day you see your daughter kicked out of a sporting event for excessive violence!” my Buddhist father proudly told people at dinner parties for roughly the next ten years. Curtsy.

[3] In this scene, Kat is wearing a blue camo tank top, a black hoodie, green utility pants and flip-flops. Mandella, who always looks as though she is perpetually weighing whether to hit the Renaissance Fair after school, is wearing a truly horrible orange jacket, maybe corduroy, embroidered with multicolored flowers, over what appears to be a red and white vest, which is worn in turn over a long lacy poet top, finished with suede knee-high lace-up boots, and wait, is that, yes, a snood. A snood! (Not for nothing: what season is it? I know it’s the Pacific Northwest, but still.)

[4] Except Mandella, bless her.

[5] There are no best friends in Shakespeare’s plays, because why have a best friend when you can simply monologue to the audience? But in romantic comedies, everyone needs someone to talk to, otherwise the audience would have no idea what was going on.

[6] Double Your Pleasure; Get More; Bet You Can’t Eat Just One, Once You Pop, You Can’t Stop; There’s Always Room for Jell-O; Go Big or Go Home; Gotta Catch ‘Em All; Obey Your Thirst; I Want My MTV.

[7]Clueless: the kids who run the TV station, the Persian mafia (“you can’t hang with them unless you own a BMW”), and the popular boys (“if you make the decision to date a high school boy, they are the only acceptable ones”).

Mean Girls: “Where you sit in the cafeteria is crucial,” Cady is informed—and she even gets a hand-drawn map, which clearly shows the tables assigned to each clique, including Preps, J.V. Jocks, Asian Nerds, Cool Asians, Varsity Jocks, Unfriendly Black Hotties, Girls Who Eat Their Feelings, Girls Who Don’t Eat Anything, Desperate Wannabes, Burnouts, Sexually Active Band Geeks, and of course, the Plastics.

Heathers: the lunchtime poll gives us a tour of the rich kids, the nerds, the jocks in matching jackets, and (importantly) Christian Slater in the back corner. “Why can’t we talk to different kinds of people?” Veronica asks. “Fuck me gently with a chainsaw,” says Heather Chandler. “Do I look like Mother Teresa? If I did, I probably wouldn’t mind talking to the geek squad.”(In Grease they wear matching jackets for accuracy. In Heathers they do something similar, with the added element of color-coding.)

Finally, and sorry for this, but consider the Harry Potter universe, in which on their first day of school students are literally sorted. Importantly, what they want has something to do with it, but their families, natural abilities, and emotional lives are also considered. And they’re like, eleven. And also wizards.

[8]Important: what’s the deal with Patrick and Club Skunk? This is a mystery whose answer has long eluded me. When Michael and Cameron bring it up with him, he’s immediately defensive: “I can’t be seen at Club Skunk, all right?” But when he does go, enticed by the fact of Kat’s black panties, the bartender knows him by name. So has he been there before? Does he have an ex? Does he secretly actually love Bikini Kill and the Raincoats but won’t admit it? Does Club Skunk host black market organ swaps on Sundays? I want to know.

[9] Cameron and Michael don’t say much to Kat’s face—well, she’s scary, and they’re only sophomores—but they too define her in this film (“I noticed she’s a little anti-social”), and in fact, the whole plot rests on their interpretation of her.

[10] Incidentally, Susan May Pratt also plays the best friend—though perhaps it is more accurate to call her the best frenemy—of Melissa Joan Hart (remember when these three-part names were all the rage?) in Drive Me Crazy. I remember reading once that Pratt’s character in that film had originally been written to speak only in newspaper headlines. Now I can’t verify that information anywhere, of course, but I choose to believe it anyway. Susan May Pratt: the girl morbidly obsessed with Shakespeare; the girl who speaks in headlines. In both cases, the trait is tantalizing, suggestive of a whole world of a person, even if we don’t see her yet. Even if she doesn’t exist anywhere outside of our minds.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.