The Life and Times of McDermott and McGough, True Artists of Downtown NYC

From Modern Calvary in the Catskills to Small Penis Paintings

In 1985, a gallery opened on Bleecker and Crosby that, for six months, became the hottest, coolest gallery downtown. The gallery asked to meet with us to make a show for their pumpkin-colored walls. Rene Ricard was there most days, along with Terry Toye, the trans model who worked with Stephen Sprouse and walked Chanel’s catwalk in Paris. The gallerist also slept there on the floor. Hip, cute boys hung out wearing eyeliner and black leather jackets. Warhol and Mary Boone showed up at one opening. Maripol opened a fashion boutique across the street, and Madonna (Maripol styled her famous look) let her use her name for a line of jewelry with multiple plastic rubber hoop earrings and bracelets. And then Madonna changed her style to a blond Marilyn Monroe look.

David came up with the idea of making a ten-foot-wide painting of the crucifixion with Matt Dillon as Christ, singer Billy Idol as a slave, and Attila (the hot male model of the moment) as the good thief. McD made a deal for 30,000 dollars for the idea. Diego couldn’t believe that he did it and giggled when we handed him 10,000 dollars as his cut. We ordered the enormous stretcher and had a cross built and put it in our studio at the Middle Collegiate Church. The gallery had two silent partners. One backer was the brother of a famous fashion photographer who would later die of AIDS and the other was the son of a well-known clothing designer who went to prison.

With this money we were going to start the Calvary painting and set ourselves up in the Hudson River Valley to make 13 paintings depicting Christ and his apostles naked in the landscapes for a show in Naples, Italy, with the famous dealer Lucio Amelio. In only one month we had spent all the money and needed more. Diego yelled at us and said we should have used the money to live on for the next three months.

We found a floor in the Masonic Lodge in Catskill, across from the jail, for our studio. We went to 13 sites and made sketches. It was somewhat performance-based but was unrecorded except for a photo of me by Vivian at the Delaware Water Gap. McD went immediately into wallpapering mode on the arts-and-crafts Masonic interior with dollar-a-roll paper from an old paint store in Albany. When we were in Albany we’d always stop in a dockworkers’ restaurant for the most delicious fresh fish sandwich and fries for a dollar fifty. We sat there in high starched collars and high button shoes among the macho truck drivers and dockworkers smoking at the counter downing their steins of beer.

Back at the studio McD kept wallpapering. We’d get into arguments when I wanted him to get back to work and help with the paintings. He would shout back, “You’re the one who wanted to be an artist! If you wanted to be a hairdresser, we’d have a salon and do marcel waves!” So I would block out the paintings and fill them in, and later David would sit for hours each day painting in tiny leaves, branches, and rocks. Painting with him was easy and enjoyable. On the Bowery I had started a painting of lovers ready to jump over a cliff and then went to see my mother in Syracuse. When I returned, David had blocked out a vista of the Hudson River below them with a steamship. He asked if I liked it. “I love it!” I exclaimed.

For the Hudson River School paintings we took an old tin painting box we had and filled it with new paints, brushes, and glass bottles of linseed oil and turpentine, and then set out with little stretched canvases to paint at the 13 chosen sites including Kaaterskill Falls, Catskill Creek, and even Niagara Falls. We left our hotel just near the cascades at sunrise to paint Niagara. But after a few hours, bus after bus of tourists used us as their background for travel pictures and kept asking questions. Not feeling very friendly, and wanting to finish before the place became mobbed, I dashed through the sketch and hurried off.

On the bus back to the train we met a beautiful blond fellow who struck up a conversation with us. He knelt on the seat in front of us to chat. We were thrilled that this beauty took an interest in us, and McD was quite enamored and spouted frivolity. Then the blond Adonis asked us, “Do you accept Jesus Christ as your own personal Savior?” David paused and replied, “Well, I think of myself as Jesus!” The flaxen god turned silent and sat back down in his seat.

McDermott then took Warhol to a corner and told him how we made smaller penis portraits that we weren’t showing.

A week later we went into the Adirondacks to paint another vista. After a few hours the sun was setting, so we gathered our belongings and started down the mountain, but we quickly realized we were lost.

We climbed another mountain, and when we arrived at its peak, all we could see was more mountains. I could feel my heart in my throat as the gloaming was upon us. My body was tingling with fear. I remembered from when I was a child my father volunteering to look for a little girl who was lost in this same vicinity for weeks. I didn’t say a word, but my mind raced with scenarios of being eaten by bears or coyotes, or two skeletons in Victorian clothes found in the distant future. McD started to sing an old hymn, “He Leadeth Me,” as we descended the mountain. I was too scared to get annoyed. Finally, after two hours of searching we came to a farmer’s house in a cornfield and found the road back.

We continued to make the 13 oil sketches to work from for our show in Naples. We brought the sketches back to our studio in the Masonic Lodge in Catskill, but the paintings took longer than we had thought, since David continued wallpapering the arts-and-crafts interior in period papers. We also rented a small apartment in a run-down 18th-century house in Athens, New York, which had a barbershop across the street that looked like it could have been the cover of The Saturday Evening Post.

We heard that Rene Ricard had bought some thrift-store paintings and signed them McDermott & McGough & Cortez, and the pumpkin-colored gallery on Bleecker Street that we were making the Crucifixion painting for had a showing of Rene’s paintings. We were furious with the gallery, as was Diego, for mocking us so publicly by having this show of fake McDermott & McGough paintings.

We ran into Massimo and he took us for some ice cream and told us he was opening a gallery on East 11th Street and Avenue A. In his thick Italian accent, he said, “If you’re not working with Diego, I’d like to have you represented in my gallery. It has to be between just us.” We let him know we were on our own. He asked us to prepare a show for the gallery. The downstairs parlor-floor apartment on Avenue C became available. Of course, David had to have it. We convinced the landlord that we would use it on a month-to-month agreement, with no lease. We started working furiously on the show. I had to ask McD to stop his “de-vinylization” of the new floor and get to work on the paintings.

Other than the Crucifixion, we usually painted small canvases, and McD wanted to make larger paintings. Maybe Schnabel’s large canvases had inspired him. When we were in the middle of painting for the future exhibition, Massimo received a lawyer’s letter from the Bleecker Street gallery demanding the 30,000 back or they would stop us from showing with Massimo. Massimo got hysterical. “Where am I going to get 30,000 dollars?” he cried, as he hung his head in his hands.

At that time, the art world was more conservative and didn’t like the commercial world.

There was a pretty young blond southern woman named Candy Coleman who worked at the front desk. She had the sweetest demeanor and McD adored her southernisms. Massimo had mixed feelings. “I don’t know what to think of her,” he lamented.

“Why?” we asked.

“I don’t know. She’s nice, but she’s . . . ah . . . too nice,” he continued. “She always seems to be in a good mood: ‘Good morning, Massimo. How are you today, Massimo? Can I get you something, Massimo?’ Nobody can be this nice or friendly. I think she’s hiding something.” We burst into laughter.

“She’s southern, Massimo,” David told him. “It’s a southern tradition to be polite.”

“Well, I don’t know any southerners,” he said, thinking it over.

One day he was fretting to Candy about how to get the money. “I have money if you need it,” Candy told him.

“Whaaaaaaat!?” Massimo screamed.

Candy set up a contract, and in it she took our best painting, The Scapegoat, as part of the deal. The other gallery was paid, and the show went on.

John Patrick Fleming had a beautiful brother, Brian, who looked like a young Joe Dallesandro, the Warhol actor. Brian had been in and out of reform schools and had a muscular prison body with a few homemade tattoos. I started an affair with him. Brian and a young French dancer McD had a crush on would model for us. We made paintings of the two as young lovers full of longing and lost love. I think we made the show in a few months. I’d pose the models and paint in the backgrounds afterwards. McD was good at the details. As we got closer to the opening, we painted full days, and since we didn’t use electric light every moment counted.

A week before the show opened in 1985, we moved the wet paintings to Massimo’s gallery and did the finishing touches there. We had an announcement card printed that read in bold type: attention and attention! come see the large paintings of mcdermott & mcgough. We painted the white gallery two shades of green like the halls of an old school. McD had Massimo buy two large terra-cotta-potted palms and placed them on Persian carpets to hide the cement flooring. We had Brian tend the bar in a vintage white soda-jerk outfit he had worn for a painting that was in the show, one of nine about the life of a young man in the 19th century. At the opening, Julian came with Diane Keaton and went about helping to sell the show after he had picked the painting he wanted first.

Philip Niarchos bought one, and another collector said, “I’m rich enough to buy one later, to wait and see if they make it.” That night the show sold out, with a mob filling the gallery and pouring out into the street. It was a packed house of East Village artists and admirers. Andy came with designer Stephen Sprouse. David took Andy around the show, and he bought a painting of our homoerotic version of Pygmalion. “Can I get an artist discount?” he asked.

David brought Andy over to meet Brian. “Doesn’t he look like Joe Dallesandro, Andy?”

“Yeah. Sure. I guess,” Andy replied.

McDermott then took Warhol to a corner and told him how we made smaller penis portraits that we weren’t showing. He said they were in the back of the gallery, where we showed them privately.

“Oh. I want to see them!” Andy begged.

By the late 1970s, Andy Warhol’s contemporaries had lost interest in him and his artwork.

“Not now, Andy—Massimo put them away. I’ll ask him to show you at the end of the opening.” I couldn’t believe McD was making this all up. As Andy was leaving, he came up to us and asked when he could see the penis portraits. I didn’t know how David was going to end this gag. Massimo came up to us and Andy asked about the paintings.

“What!” Massimo laughed, and in his broken English said, “Paintings of-a cocks?” Still laughing, he pulled us away to meet a collector. “Okay, Andy,” he said, “we get the cock paintings to-a you.”

The crowd thinned out, and we headed to a restaurant in the Financial District, an intact old German-style place complete with its entire original wood paneling, crystal chandeliers, and a mural of ancient Egypt. David ordered his favorite meal of a Thanksgiving turkey feast served with all the trimmings, at a long table for 80 people.

The art world was smaller then, and most of the people in it knew one another. SoHo became the Saturday place for going around to the galleries, and Sunday was for the East Village galleries. SoHo galleries were big and dramatic. East Village galleries looked dingy, and Massimo was criticized because his gallery looked more SoHo than East Village, with high ceilings, perfect white walls, and a polished cement floor. He was also criticized for being friends with such successful SoHo artists as Francesco Clemente and Julian Schnabel and their glamorous wives, Alba and Jacqueline.

One Sunday while we were at the gallery to look at the exhibition, David Hockney and Henry Geldzahler walked in. I don’t know what the others there thought, but I was dumbstruck. Hockney had been an important influence in my early life. I loved his portraits of Ossie Clark, the English designer, and the one of Geldzahler on his pink sofa. But we left them alone as they looked over the show. I heard later that Hockney thought one of us painted the people and the other did the background. We never had those kinds of rules. We knew each other so well, and the one thing we never fought about was what the other painted.

By the late 1970s, Andy Warhol’s contemporaries had lost interest in him and his artwork. They thought he had sold out, hanging with Halston and Liza at Studio 54. And when he appeared on the television show The Love Boat, they lost all respect. But my generation loved him.

We all wanted to meet him. Douglas Cramer, an art collector and the producer of The Love Boat, told me that Andy said he’d be on the show if Doug could encourage movie stars to have their portraits done. So Doug had a big party with Andy and many famous actors. Andy was in heaven. But the portraits didn’t come through, so Cramer commissioned some on his own.

At that time, the art world was more conservative and didn’t like the commercial world. They also did not like that Keith Haring had his Pop Shop. Andy took all of that in and he proved to be a big influence and visionary, and now it seems he was way ahead of his time, but his generation felt disdain for him.

The first time I found out how much his generation didn’t respect his work was when the art critic Robert Rosenblum and his wife, the artist Jane Kaplowitz, bought a large Warhol self-portrait in red with a shock of hair that went to the top of the painting. They bought it in 1986 from the Anthony d’Offay Gallery in London. Jane told me they had the pick of any painting. The Rosenblums always gathered an interesting group around them—everyone from Jasper Johns, who rarely said much, to Philip Johnson and David Whitney, who were a lot of fun, and other art dealers, critics, and artists. The painting they bought was the only painting that sold in that show at the time. After they installed it in their living room, they were criticized for buying a Warhol.

“Why would you want a Warhol?” friends would ask. Robert in his brilliance defended the portrait. There was also a story that at an art fair, when a gallery installed a whole booth of Warhol’s work, the galleries on either side complained that their booths, artists, and artwork would suffer because of it. That’s how badly his work was regarded. When the art dealer Howard Read wanted to show some of his photographs that he’d sewn together in groups, Andy’s main dealer, Leo Castelli, had little interest and said to go right ahead. I once asked Andy if he had seen the latest issue of Artforum: his painting of Life Savers was on the cover. “What did they say? I’m too commercial?”

One of the great things about Andy was that we could drop by the Factory on 33rd Street whenever we wanted. Brigid Berlin would usually be at the front desk, doing needlepoint and casting a jaundiced eye on everyone. She knew how to make you uncomfortable, we were extra polite, but it made no difference. David always went up to her: “Good afternoon, Messrs. McDermott and McGough are here to see Andy Warhol.” Without a word, she’d pick up the phone. “Those old-fashioned people are here again,” she would say, hang up, and go back to her needlepoint.

Andy would appear on a balcony above a taxidermied elephant painted over by Keith Haring. “Oh, hi. Come on up.”

At a long table there would be a lunch either starting or ending. We always hoped it was starting. It would be for a celebrity, a client, or advertisers for the magazine. His assistant Ben Liu (drag name Ming Vase) and Paige Powell, his pretty gal Friday, would usually be there. If we had a cute young fellow we were interested in, we would bring him to Andy for the “Wow” effect.

I always felt Andy was clever to surround himself with young people. We all adored him, worshiped him, and wanted to know him.

_________________________________

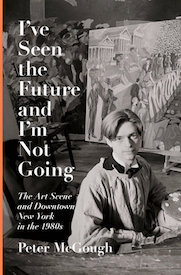

From I’ve Seen the Future and I’m Not Going: The Art Scene and Downtown New York in the 1980s by Peter McGough. Used with the permission of the publisher, Pantheon. Copyright © 2019 by Peter McGough.

Peter McGough

Peter McGough is an artist who has collaborated with David McDermott since 1980 as McDermott & McGough. They are known for their work in painting and photography. McGough divides his time between Dublin and New York City.