The Library is Open: On Party Girl, Budget Cuts, and the Future of Women’s Work

Victoria Wiet on the 1995 Cult Classic, a Rallying Cry for Libraries

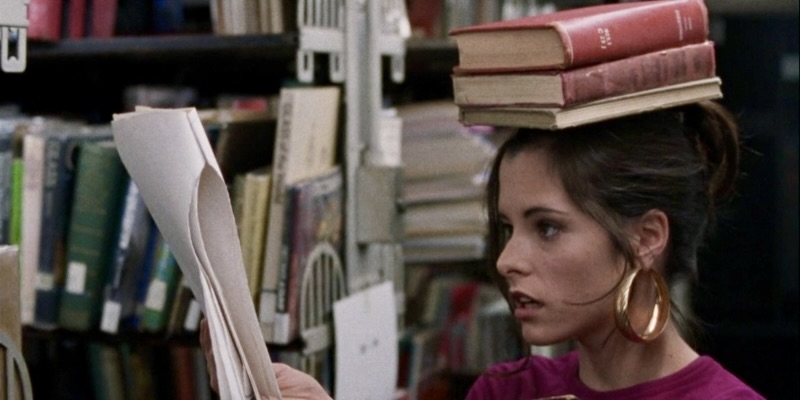

Now screening on the Criterion Channel—and perhaps at an arthouse cinema near you—is a new 4k restoration of Daisy von Scherler Mayer’s debut film, Party Girl (1995), starring indie queen Parker Posey. Party Girl has become a cult classic for its heroine’s wardrobe of 90s couture and its documentation of Manhattan nightlife during that liminal period between the worst of the HIV/AIDS epidemic and the sanitizing project of Rudy Giuliani’s mayorship. But sometimes, the film ceases to be a deliciously camp time machine and becomes a drolly realist harbinger of the future. In an early scene, when Posey’s Mary visits her godmother Judy at work to thank her for bail money, Judy laments, “we are reeling from budget cuts.”

There are many fields where one could expect a manager to deliver this line, but Judy’s profession will be especially unsurprising to anyone with ties to New York City: she’s a librarian for the New York Public Library. Though NYPL staff and city councilors recently pressured Mayor Eric Adams to exclude the city’s library systems from a budget reduction of four percent, another proposed cut of $36 million remains in place today.

In fact, cuts to the NYPL sets Party Girl’s entire narrative in motion. Judy’s line comes during a conversation in which she exhorts her goddaughter to get a job, only to be interrupted by a patron complaining about every Hannah Arendt book being out of sequence. Unable to retain clerks because she can’t “pay them a competitive wage,” Judy briefly raises and then dismisses the possibility that her cash-strapped goddaughter could be the solution to her staffing issues. Mary’s pride compels her to prove that she could excel in the role, and so begins a journey in which a young woman most known for her voguing skills must learn how to diligently reshelve, politely assist patrons, and master the Dewey Decimal System.

The film’s portrayal of properly reshelving books as a Sisyphean task—to reference one of its key allusions—is laugh-out-loud funny. But as a former library worker and passionate library patron, I see Mary’s introduction to library work while wearing designer stilettos as more than a source of comedy. Against the backdrop of a culture that deems libraries as expendable during periods of economic downturn, Party Girl launches a defense of librarianship as indispensable to women’s self-actualization and a society’s collective knowledge.

*

Party Girl, as its director and star often point out, is a modern screwball comedy, a genre whose enduring appeal can be attributed to its women-driven narratives. As critic Molly Haskell famously explained in From Reverence to Rape (1974), the enforcement of the puritanical Production Code had a paradoxically feminist effect on 30s and 40s Hollywood filmmaking. In place of the oversexed party girls of those late silent and pre-Code comedies starring Clara Bow and Mae West, screwball comedies made heroines out of clever working girls who used their verbal wit, rather than their bodies, to wage the battle of the sexes. But the intelligence of these working girls is not always immediately recognized. In a classic of the genre, Billy Wilder’s Ball of Fire, the Brooklyn-born Barbara Stanwyck plays a burlesque dancer who initially attracts a group of stuffy male professors because of her shapely legs but later integrates herself into their household through her adroit use of language.

Posey herself has spoken of her affinity for Stanwyck, and in Party Girl, she proves herself at ease in the “fish out of water” trope which structured Stanwyck’s best comedies. The film’s cinematography draws a stark contrast between Mary’s preexisting habitat, the hazy nightclub and her dimly lit Soho loft, and the starkly fluorescent NYPL branch where she spends her daytime hours. In lieu of the house music and R&B that pulsates through her nocturnal life, the stamping of due dates is the only soundtrack Mary experiences behind the library desk. And like a true screwball heroine, Mary reacts to feeling out of place with cutting wit. After Judy chastises her for incorrectly coding Freud’s Dora, thus failing to meet the standard set by the trained monkeys who reportedly mastered Dewey’s classification system, Mary retorts in a fantasy monologue, “It is dismaying that your expectations are based on the performance of a lesser primate, and also revelatory of a managerial style which is sadly lacking. Is it any wonder then, that I have chosen not to learn the intricacies of an antiquated and idiotic system? I think not.”

Party Girl launches a defense of librarianship as indispensable to women’s self-actualization and a society’s collective knowledge.

By calling the Dewey Decimal System “antiquated and idiotic,” a blisteringly apt descriptor for us Library of Congress partisans, Mary forces the viewer to recognize that she is much smarter than she is given credit for. As the film continues, von Scherler Mayer makes it clear that not only can streetwise heroines be booksmart, too, but that being a rave queen can actually prepare you to succeed as an apprentice librarian. In Party Girl’s most memorable sequence, Mary sneaks into the library at night to give herself an independent tutorial on Dewey’s “idiotic system.” The sequence cross-cuts between the library and the nightclub, where close-ups and pans over dancing hips alternate with shots of Mary’s friend Leo working his first shift as a deejay. But here, the stark contrast between the nightclub and the library breaks down. Leo’s discs continue to play as Mary studies the library, and cuts between shots of different aisle markers and card catalogue drawers occur in sync with the music’s syncopated beat. The library becomes Mary’s dancefloor as she turns a table into a catwalk on which she balletically reshelves books and perches herself on a desk to close card catalogue drawers with her designer boots.

The sequence is fun to watch, but the analogy it draws between dancing and shelving also reveals something important about library work. When I was a circulation assistant at my college library, my working conditions were not dissimilar to Mary’s in this moment. Because no one studied in the basement level where the art and music books were held, I had the floor to myself. Using a carefully selected soundtrack on my iPod Nano as my guide, I turned the music’s structure into a unique itinerary for weaving through the stacks and altered my pace according to my soundtrack’s tempo and the needs of the books. Shelving reference works was brisk; shelving monographs about individual composers in the dense ML 410s took more time. Even with an entry-level task like shelving, I had to enact a complex system defined as much by its variations as by its repetitions.

Mary’s knack for devising such complex systems allows her to finally answer the questions that obsess her: What am I good at? What kind of work would I enjoy? The film thus teases out the drama of self-actualization implicit in screwball comedies and explicit in another Stanwyck-centric genre, melodrama. Screwballs often validate their heroine’s intelligence by culminating in an unlikely match, such as an awkward English professor and seductive stripper, but in Party Girl, the match is between a heroine and her career. Instead of a kiss, the film climaxes with Mary’s announcements “I’m serious about graduate school!” and “I want to be a librarian!” Initially skeptical of the goddaughter she thinks “just like” her aimless mother, Judy gives Mary her wholehearted support. Like the striving heroines of melodramas such as Baby Face and Now, Voyager, Mary casts off her family’s perception of her and finds a way to assert her own worth.

Mary’s journey to self-actualization through the library stacks is, in practice, one most often taken by women. Women continue to dominate the field of library science, with AFL-CIO’s Department of Professional Employees reporting that 82 percent of librarians are women. Why? Because Melvil Dewey, Judy explains in the film’s centerpiece monologue, “hired women as librarians because he believed the job didn’t require any intelligence. It was a woman’s job! That means it’s underpaid and undervalued.” Judy’s impromptu history lesson is largely accurate, for the man who helped found the American Library Association did indeed advocate for allowing women into library school because of their social intelligence and manual dexterity. Party Girl corrects Dewey’s undervaluing in part by showing how this “woman’s job” can be a meaningful path for women to acquire financial independence as well as intellectual validation.

In Party Girl, the match is between a heroine and her career.

But if the world outside the film does not value this work, then it will remain “underpaid.” It could even become subject to prophecies of obsolescence.

*

Party Girl sharply diagnoses the problems that libraries still face, but the 90s nostalgia the film now incites isn’t entirely irrelevant to its portrayal of Mary’s new profession. Nothing makes it clearer that Party Girl depicts a world without widespread access to computers than those scenes at the NYPL. In a scene where Mary scolds one patron for reshelving a book, the other patrons look up from their books, not from their screens. The only computer in this scene—and the entire film—can be spotted behind Mary, but only if you pay close attention. Out of focus and in the background, it languishes unpowered, unattended, and with no chair for a potential user.

Judy, for all her pessimism, thrills at the potential impact that computers could (and indeed will) have on library science. At one point, she tells another clerk, “I wish I were in school now—the new technology, it’s so exciting.” Her optimism is not unwarranted. As a former library assistant, I cannot fathom having had to learn a call number system through a reference book, as Mary does; instead, I completed a computer tutorial that took all of 20 minutes. As a researcher, I do not have to flip through drawers of a card catalog to learn what books my library has on a subject; I can simply plug a couple words into the online catalog’s search bar. I dare not even imagine what planning archival research was like in the pre-internet age.

Yet a world before computers is not without its allure. I watched Party Girl after a semester of witnessing colleagues catastrophize that the emergence of ChatGPT and other AI tools signals the end of higher education as we know it. Parallel conversations, my friends in the library world tell me, are also happening in their own field. Of particular concern is not the self-interested question of whether universities will still invest in libraries but the threat to information literacy. In a culture where students already turn to the unvetted world of Google to complete research papers, ChatGPT allows students to bypass the cumbersome tasks of trying different search terms and actually reading sources. Yet because such tools are designed to simply generate plausible language rather than to process and evaluate information, their output is often surreally inaccurate, and the citations they provide completely made up.

In other words, what we lose in an era of AI tools is what Ellen Sexton, chief librarian at John Jay College, calls the “traditional gatekeeping function of libraries.” Gatekeepers tend to be cast as opponents to social justice, but Party Girl cleverly dramatizes the social good which library staff generate. To help her Lebanese-born boyfriend return to the teaching profession, as she explains in her final monologue, Mary carefully built a body of knowledge that is both foundational and up to date: by first consulting national reference volumes, then refining the search by checking the latest bulletin for New York State teaching requirements, and, finally, verifying the details by using the early internet to look up any recent amendments to state law. As Mary’s process makes clear, what reference services provide aren’t a series of words that superficially resemble “facts.” Rather, what Mary does is order, evaluate, and synthesize knowledge.

And to do this work most thoroughly, Party Girl implies, librarians and their trainees must be stewards of physical repositories instead of disembodied chatbots on the library webpage which collate licensed e-books and citations from article databases. My favorite illustration of this comes when the newly confident Mary whips around on her swivel chair to retrieve a pile of books she’s culled for a patron. Within the broad field of twin studies (“There’s a lot of studies on twins”), she has selected a few pertinent to the patron’s specific line of inquiry (“these focus solely on the made-up languages”), and has even added a book of twin-composed songs (“just for fun”).

We don’t see Mary weaving through the stacks in pursuit of this reference request, but it’s not hard to imagine. As anyone who has ever reshelved library books can tell you, often, the best way to master a field isn’t to go to the catalog; it’s to go to the stacks and look at the books surrounding a single relevant title, such as one on “the made-up languages.” And when Mary adds the song book, likely shelved far away from the psychology titles, I can imagine that this is a volume Mary only thought to add because she had encountered it during a reshelving shift. It’s an unexpected addition that reminds me of those times I’ve showed up to a reading room and the special collections librarian has added an uncatalogued manuscript I didn’t know existed. Such idiosyncratic recommendations are the things that research breakthroughs are made of, and I’ve yet to be convinced that computers alone can generate them.

If economic austerity replaces libraries with Google and librarians with AI chatbots, then research innovation will falter; the authoritative information needed by those seeking social mobility will be difficult to extricate; and yet another field occupied by women will see workers replaced by automation. Party Girl does not contemplate such a future, but by depicting a world lacerated by budget cuts but not yet taken over by computers, von Scherler Mayer’s film can make this future feel plausible while reminding viewers of what makes libraries worth fighting for. Viewed from the vantage of 2023, Party Girl is nothing less than an argument for why, for the sake of women’s self-actualization and the broader social good, librarians need to be embodied minds rather than streams of code.

Victoria Wiet

Victoria Wiet is a scholar and critic whose writing on the performing arts, gender and sexuality, and contemporary British culture has appeared in Public Books, Crime Reads, Politics/Letters, and BLARB: The Blog of the Los Angeles Review of Books. She received her PhD in English from Columbia University in 2019 and is completing a book on how the Victorian-era commercialization of the theatre fostered erotic experimentation in fiction and society. She currently teaches courses in English and Film studies at DePauw University.