Header image ©1975, 2023 Joel Sternfeld

I’m no good at explaining how I came to write so much about photography, wrote an entire book about it in fact. A series of accidents, surely. Small-town western North Carolina, in the shadow of the Great Smokies, amid the Blue Ridge Mountains. My head was stuck in books, too close to the television, plunged underwater, ducked down low in the theater seats to sneak-rewatch the movie I’d just seen. Analog childhood, lucky me. Phone on the kitchen counter, everyone can hear your business, except my dad who was born Deaf (it runs in his family, we all sign). In the days before the internet, before video chat, his phone conversations are on a TTY machine that banner across a tiny screen in green calculator-font letters, which is how we all get a head start on texting shorthand. GM. TTYL. And, when you’re done talking and ready for the other person to respond: GA—go ahead.

Meanwhile, so much goes unphotographed. Drugstore processing. The surprise of what was seen, what escaped. Cutoff heads. Glowing red eyes. Kodak everything.

My own first camera’s a novelty, a Christmas present, the Kodak Disc, a little Viewmaster-like wheel instead of a roll of film. Discontinued before 1990 rolls around. A taunting commercial jingle’s still in my head, “I’m gonna get you with the Kodak Disc! Gonna get you and I’m not gonna miss!” A particular visual violence in the dirty little hands of a ten-year-old. You only had fifteen frames on those discs, as precious as Polaroids and as prohibitively expensive. This could have made me intentional and economic about my shutter clicks, thoughtful when it came to composition. But I just took pictures of my cat and my sister and our friends. The picture quality of those discs was so bad, everything looked automatically grainy and ancient, as if we were already fading away, like Marty McFly’s disappearing photograph in Back to the Future. Even though we were just wearing our usual hoodies and jeans, we painted red circles on our faces, rigged up a makeshift tightrope on our swingset and tiptoed across balancing umbrellas, made a circus. I don’t know why or for who.

Our town’s a pit stop on the interstate, a place on the way to others that were actually scenic; get raised here and you absorb a sense of in-betweenness, outsiderness. Wild to imagine that anyone not from around here would find it remarkable, interesting, worthy of looking. But before I was born and throughout my growing up, wholly unbeknownst to me at the time, some of the photographers and filmmakers I’d come under the sway of years later, were lurking close by.

The carved-out mountain

A still from Wanda (1970), directed by Barbara Loden. Courtesy of Janus Films.

A still from Wanda (1970), directed by Barbara Loden. Courtesy of Janus Films.

In the early minutes of Wanda (1970), Barbara Loden, as the drifting main character, slowly, slowly crosses a coal field as vast as a lifetime. In my eyes the field is the mined mountains I am sure she saw as a child because, years later, in the late 1980s and 90s, they haunted me too. Loden grew up in Marion, North Carolina, twenty miles up the road from me, a place I stared at from car windows, driving up the mountain to stay with best friends who’d moved away. Certain significant trailers, parking lots, porches dotted the way; a hairpin turn with a gasping view we called, with dramatic flair, The Edge. Over The Edge, naturally, a sharp cliffdrop gaped open onto a rocky mountainside and old-growth forest below. Past The Edge, back then: tourist gem mines where you could pan for pyrite and abandoned Alpine themed inns and video stores and a broad, brooding mountain whose insides, like so many around here, had been scraped out for rock and gravel and construction rubble.

That particular quarry was named after the god of fire. In my memory, the air was the color of Loden’s 16mm film, a smoky cast against the blue horizon of the mountains behind it. Loden did not film Wanda in North Carolina; she had to cut corners on her already slim-to-nothing $115,000 budget. Production took place closer to the film processing houses in New York, mostly in Pennsylvania coal mining country. Northern Appalachia is distinct from the southernmost region where I’m from, but close enough to stand in for an emotion. The smudginess of dishevelment she passes through, of the living rooms, factories, bars, diners, downtowns, discount store parking lots comes partly from the grain of the film, from the natural, documentary quality of Nicholas Proferes’s cinematography.

Loden deviated from her own script, let the open ending happen on its own, as an inevitable consequence of the way the film unfolds. “I don’t see how anybody can predetermine how their movie is going to turn out, or why anybody would want to, because it’s a creative thing that is changing every day, and you’re changing every day while you work on it,” Loden told the American Film Institute in 1971. “You start to make a movie, and when you finish it you’ll be a different person.”

The shuffled deck

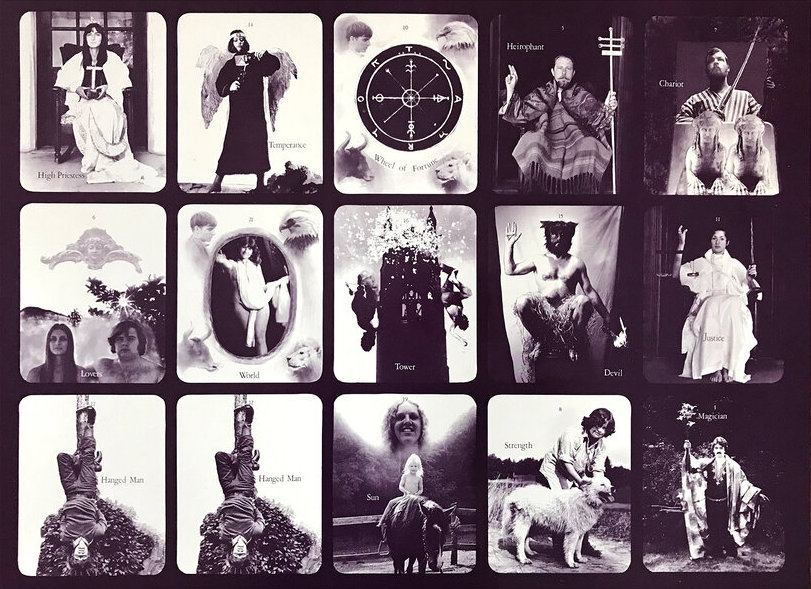

Mountain Dream Tarot, 1970, courtesy of Bea Nettles

Mountain Dream Tarot, 1970, courtesy of Bea Nettles

When we made it over The Edge and passed Wanda’s quarry-coalfield, we were only halfway up the mountain to the house where two of our best friends moved, a tinier, remote town, a little closer to what people picture when they mispronounce Appalachia. On the way you pass the turnoff to the Penland School of Craft, started by women weavers in the 1920s, a vintage lodge in the fog. You could almost picture Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain half lung club convalescing on its porches. As far as the rest of the county went, Penland was pretty much hidden away, doing its own thing. My friends and I up the road, we wished for other futures, casting our own divinations in the form of ruled notebook paper folded into MASH fortunes.

Little did we know then that Penland is also where in 1970, prompted by a dream, the artist Bea Nettles began making the first photographic tarot deck. For what became Mountain Dream Tarot, she photographed her friends and fellow artists and eventually her family in the roles of major and minor arcana, and arranged in numbers. Longhaired, mustached, folk art spirits and witches, ladies of the canyon dresses, defeated men who look as if they’re about to head out on “the lam,” a spectral child atop a donkey, they are of their time and timeless, They carry sticks as wands, and alpine mist in the frame. Plucking the stars from the sky, Nettles turns them into pentacles, scatters them in the water where a woman bends down to drink.

The town witch

Doesn’t everywhere have one? Once, she sails into the corner store where my grade school self is about to blow the last of my pocket money on Sweet Tarts. In my memory she’s buying long, lean witch cigarettes—Virginia Slims or Capris—but all I can truly recall is how everyone swivels to look at her: clad head to toe in black like Elvira or Priscilla Presley, from the upswept dyed hair to the thick curtains of faux lashes, the silvery shadow dabbed all the way up to the shoreline of her painted-on brows, to the lowcut dress and pointy. The town witch briefly attempted her own country music career in Nashville: no hit records, but for a while she dated a man who claimed to’ve been a bus driver for Elvis.

A half dozen times a week we ride right past her house, less than a mile from ours, a little stone bungalow named Gray Shadows, its engraved wooden sign hung by a chain over the yellow door, and back then, a yellow AMC that my sister and I both coveted parked out front. We never go in. The town witch would simply be a Boo Radley figure to us, that is, if she weren’t always showing up in the local paper. An actual headline: “Local woman claims clown doll isn’t creepy.” (The doll, the story goes on to say, was pinned to the front door of Gray Shadows.)

The town witch runs for mayor, vowing to outlaw public toplessness for men unless women are allowed to go topless too. Fair! She claims, at one point: “I think I invented streaking.” Her actual claim to fame is that she’s the first woman in modern U.S. history to be tried for witchcraft in connection to an alleged murder—eyebrows raised after she accurately predicted another woman’s death to the date in a seance. (The town witch was acquitted, but the story is notorious enough that in 1976 Esquire sends a reporter to do a feature. For the spectral, shadowy impressionistic portraits of her, they send Duane Michals, whose photographs are already refreshingly unserious worlds of their own, little dances into the afterlife, unafraid to try to depict the things we’re told do not exist.)

Today the town witch is supposedly 90, a haze surrounding her precise birthdate. “I’m a good person till people bothers me,” the witch told a filmmaker recently, another former local who makes an extended YouTube video about our town. Her accent is wild—like mountain ladies who might’ve befriended my grandma, like she’s channeling someone from her seance table. “Listen to your conscious,” the town witch says. “If I’m going to the store and I have a strange feeling, I don’t go inside.”

The dunes

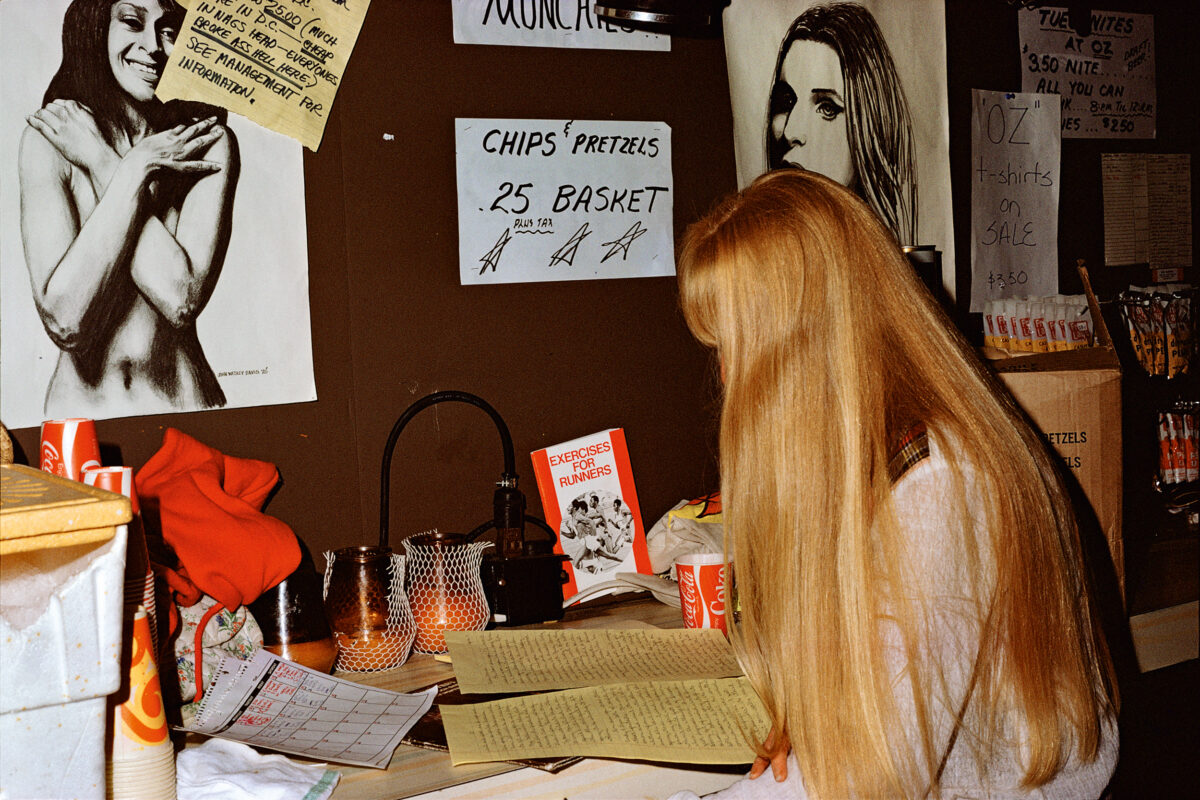

©1975, 2023 Joel Sternfeld

©1975, 2023 Joel Sternfeld

To be fair, a long long drive from us—but worth the annual beach trek even back when car seats stuck to the backs of your thighs, surfing the radio the whole way. The eighties still looked an awful lot like 1975, as if the pictures Joel Sternfeld made that summer had actually frozen Nags Head, and beach towns like it, in time. If only photographs had that power—further south on the Outer Banks, in Rodanthe, giant houses are slipping away into the ocean. Perhaps they should’ve stayed small and kept their distance from the shore like the wooden bungalows Sternfeld photographed, painted plain white or stormy ocean green. Some of them, if not THE ones he photographed, are still in Nags Head, survivors amid the condos and the eight-bedroomers. Some look like little prairie farmhouses spirited away in a Kansas tornado and plunked down among these giant, horizon-swallowing dunes. Picture inside them still Sternfeld’s vividly sunburnt teenagers drinking sandy beers; all those saturated feelings. And at the end of it all, the visual planes of sky, water, beach flattened in the frame, like the memory I carry in the rearview mirror at the end of each summer visit, slowly disappearing as we ride further west, back to where I came from.

The senator

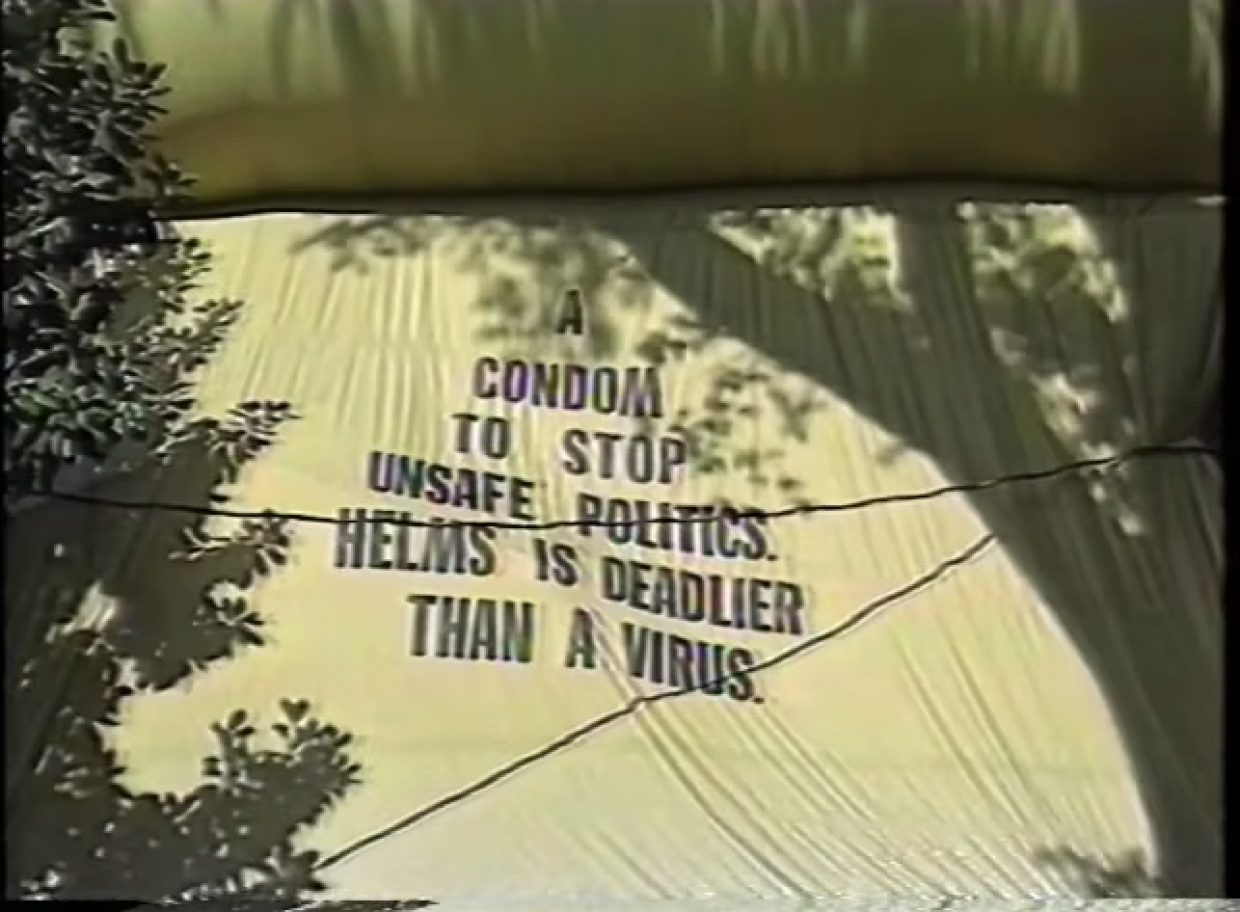

Via Poz.com

Via Poz.com

“Helms is deadlier than a virus,” read the words printed on a giant yellow condom a passle of ACT UP activists brilliantly wrapped around the Arlington, Virginia, home of blight-on-North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms. Helms’s fight to ban Robert Mapplethorpe only helped me to see his work sooner, connect the dots between the photographer’s portrait of Patti Smith on the cover of Horses and the nudes and BDSM shots that made the senator clutch his pearls. Helms’ boundless racism bled into his homophobia, and his vicious fight aginst federal funding for HIV research and treatment.

His banning of Mapplethorpe would be my gateway to all the other brilliant photographers that Helms ensured died young: Peter Hujar, dead in 1987 at 53; William Gedney, dead in 1989 at 56; Darrel Ellis, dead at just 33 in 1992. Cookie Mueller, writer and actress, not a photographer, but star of Hujar’s photographs, of Mapplethorpe’s, of Nan Goldin’s, dead at 40 in 1989. David Wojnarowicz who in 1988 painted a pink triangle on his leather jacket and the words “If I die of aids[sic], forget burial—just drop my body on the steps of the F.D.A.” When Wojnarowicz did die of AIDS, in 1996, at only 37, his ashes were scattered on the White House lawn. Somehow Helms remained in office through the deaths of every one.

The last mall

In 2021, Stephen Shore, whose seventies photographs of American parking lots became icons in their own right, returns to the lot with a drone that he happens to, one morning just before speaking to Peter Schjeldahl in one of the critic’s last interviews, fly over the shopping mall of my youth. Valley Hills, where I had my twelve-year-old birthday party at the food court, where over the triangular orange blaze of my Sbarro slice, I aspirationally eyed the mall goths and mohawked punks circling the fountain, where I later discovered you could buy outdated copies of the Village Voice and NME, all the way in Hickory, NC. Dead malls, abandoned malls, all the rage these days—I love them too. But now mine lives forever.

To smoke until all her cigarettes were gone

Amanda and her cousin Amy. Valdese, North Carolina, 1990. From Mary Ellen Mark: The Book of Everything. © Mary Ellen Mark. Used with permission of the Mary Ellen Mark Library.

Amanda and her cousin Amy. Valdese, North Carolina, 1990. From Mary Ellen Mark: The Book of Everything. © Mary Ellen Mark. Used with permission of the Mary Ellen Mark Library.

An earring dangles from just one lobe, ending in a plastic pearl. The wearer, in mascara, lip gloss or stick, and press-on nails, juts her hips, standing in the four-inch lake of a kiddie pool, blowing smoke at the camera. Holding her elbow and giving a look like she’s about to tell you just what she thinks of the people next door. Not like a rowdy nine-year-old kid in a “problem school” that Life had sent Mary Ellen Mark to cover.

The first time Mark met Amanda, she followed her home, at a distance. Amanda hopped off the school bus and promptly vanished into the woods, to sit in an old chair there, as was her habit, and smoke until all her cigarettes were gone. Most of the problems with the “problem kids” in the school were the adults, Mark understood. She was my favorite, Mark remembered long after. Amanda lived in a housing complex nicknamed Sin City, in a little town nine miles away from mine, where I and a few motley friends had begun to go spend all our money at a secondhand record store whose survival in that place felt to us as unlikely as our own.

I didn’t know Amanda, but I knew girls like her, girls who were somehow already twice their actual age, girls who got yelled at by the teachers in front of everyone, girls who you just knew were going through even worse shit at home, who you hoped, hoped, hoped would get out. Amanda did, but it took years.

A still from Blue Velvet (1986), directed by David Lynch.

A still from Blue Velvet (1986), directed by David Lynch.

By the time I see David Lynch’s Blue Velvet it’s the 90s, I’m hooked on his Twin Peaks, but I loved, perversely, intensely, knowing that Blue Velvet was filmed in another beach town we’d go to over and over. Wilmington, North Carolina playing the role of “Lumberton.” Not exactly next door but close enough to confirm that the underground was within reach. What else spoke to teenage me more than than the surreal creepiness of a human ear found in a field? Mine pricked up.

_________________________________________________

Strange Hours: Photography, Memory, and the Lives of Artists by Rebecca Bengal is available now via Aperture.