The Legendary Meeting of Robert Plant and Jimmy Page

Bob Spitz on the Men Behind Led Zeppelin

On July 20, 1968, Robert Plant was performing at a teachers’ training college in Walsall, in the West Midlands, with a rather unimpressive group called Obs-Tweedle. The audience was practically nonexistent, just a handful of kids who were already pretty tanked up on beer, hardly paying attention to the band. Jimmy wasn’t wild about the music, either. “The group was doing all of those semi-obscure West Coast kind of numbers,” he said, things by Moby Grape, Jefferson Airplane, and Buffalo Springfield. “The band overplayed, and there was a lot of hubbub and flash.”

But . . . the singer! It was impossible to take your eyes off him. He was tall and lanky with skintight jeans and a resplendent halo of hair, which he kept sweeping off his face like a Hollywood ingenue. He moved like an ingenue, too. “He had a distinctive sexual quality,” as Jimmy remembered it, almost feline, androgynous in his gestures but in total command of the stage. And . . . the voice. At times it sounded like an unrefined Stevie Winwood, earthy and uninhibited, but it also soared into a “primeval wail,” which could be unnerving, coming out of the blue as it did. It was the whole package, but it worried Jimmy. “His voice,” he said, “was too great to be undiscovered.” What was he doing in this godforsaken backwater? Why hadn’t he caught on with a top band by now? “I immediately thought there must be something wrong with him personality-wise, or that he had to be impossible to work with.”

Afterward, when they were finally introduced, Jimmy explained the seeds of his new venture, and Plant gave Jimmy a demo he’d done with the Band of Joy—three songs: “Hey Joe,” “For What It’s Worth,” and a Cyril Davies number Robert had rewritten as “Adriatic Seaview”— that they’d recorded at IBC Studios in 1967. “We did the whole thing in just a half an hour,” recalls Kevyn Gammond, who played soaring Hubert Sumlin–style solos on the session. “The engineer just put mics up and said, ‘Okay, play your songs,’ so they all went down in one take.”

That session might have been slapped together, but the result was as uncompromising as anything Led Zeppelin ever recorded. The brutality of the attack was unmistakable. Robert’s delivery was genuinely stirring; it wrung all the tension and excitement out of the material. John Bonham’s adrenaline-fueled drumming was like the finale at the end of a fireworks display; it made the earth move. It sounded like no one else. Listening to the scratchy acetate, Jimmy heard the future. This was close to the sound he’d been dreaming about.

Jimmy admitted to Robert that he’d already made a pitch to Terry Reid, whom Robert admired, but said, “You know, I think we should get together. If you’re interested, come down and spend some time at my place. We’ll go through some sounds and records, see if we’ve got the same idea, if we’re sympathetic, and take it from there.” Jimmy wanted to be sure the chemistry was right. “It was obvious he could sing and had a lot of enthusiasm,” he recalled, “but I wasn’t sure about his potential as a frontman.” Jimmy invited Plant to the house he’d bought in Pangbourne, just west of Reading. “Why don’t you bring some of your favorite records down?” he said.

Robert’s delivery was genuinely stirring; it wrung all the tension and excitement out of the material.

Dutifully, Robert went through his precious stack of records and chose a selection to play for Jimmy Page: “Joan Baez’s ‘Babe, I’m Gonna Leave You’ and ‘Farewell, Angelina,’ Howlin’ Wolf’s rocking chair album, 5000 Spirits by the Incredible String Band,” he recalled. “And my gatefold Robert Johnson album on Philips, which I bought while I was working at Woolworth’s. That was the jewel in the crown.” He stuffed them into a satchel and hopped an express train from Birmingham to Reading, where he connected to a commuter train to cover the remaining short distance to Pangbourne.

Jimmy, now 24, lived just down the hill from the station in a 150-year-old Victorian boathouse plunked behind a pub called the Swan. “It’s very big, with six bedrooms,” he said by way of description. “It has three stories and there are boats downstairs.” The interior was decorated with an array of posh art deco and art nouveau artifacts he’d collected as his fortunes rose, along with paintings, books, model trains, and a tank full of tropical fish. The home’s focal point was a big stained-glass window that overlooked the River Thames. This was a big change from the cell-like childhood bedroom he’d vacated just two years earlier.

Plant was duly impressed. He was only 19, he was broke, living in a spare room above a pub in Wolverhampton, at a standstill career-wise, and this place had all the trappings of rock ’n roll success. Also in residence was a “quite sassy American girlfriend” who took his breath away. Jimmy’s hi-fi equipment alone was a pretty swank affair—a mammoth Fisher amplifier with Tannoy speakers, several reel-to-reel tape decks, the kind of setup one expected to see in a full-service recording studio.

It took Jimmy and Robert a while to get comfortable. They were so different in their backgrounds and experience. Robert was unsophisticated, humbled, even awed by his initial brush with the more cosmopolitan, well-traveled, super-successful Jimmy Page. “The way he carried himself was far more cerebral than anything I’d come across before,” Robert admitted.

It was music that finally broke the ice. They talked into the night about Elvis, Jerry Lee, Chuck, Buddy, and Eddie, as well as Sonny Boy Williamson, Johnny Burnette, Ben E. King, Otis Clay, and Solomon Burke, whose songs rolled off their tongues. “I looked through his records one day while he was out, and I pulled out a pile to play,” Robert recalled. “Somehow or other, they happened to be the same ones that he was going to play when he got back, to play to me to see whether I liked them.” Jimmy laid on a full banquet: Muddy Waters’s “You Shook Me”; “If I Had a Ribbon Bow,” one of Fairport Convention’s masterpieces; “She Said Yeah” by Larry Williams; “Justine” by Don and Dewey; and their mutual pick, “Babe, I’m Gonna Leave You.” It was clear that they were on the same wavelength.

“His ideas were fresh, and they excited me,” Robert said.

Conversation eventually turned to the group Jimmy intended to form. There was already a bass player in place. Chris Dreja had announced his decision not to join, so Jimmy was leaning toward John Paul Jones, his friend from session work with a prodigious list of credits and a reputation for being a musician’s musician. They had bumped into each other while working on an album, No Introduction Necessary, with newcomer Keith De Groot. “During a break, [John Paul] asked me if I could use a bass player,” Jimmy recalled. It was a surprise, but not without precedent. Jones, like Page, suffered from the session man’s malaise and ached to play in a band where he could express himself freely. “I was making a fortune [playing sessions],” John Paul recalled, “but I wasn’t enjoying it anymore.” Nothing concrete was decided at the time, but sometime later his wife, Mo, noticed an article in Disc reporting on Jimmy’s intention to form a band out of the old Yardbirds. “She prompted me to phone him up,” John Paul said, and on July 19, 1968, the day before the Band of Joy performance in Walsall, they made it official.

“Jimmy told me about John Paul Jones,” Robert noted, “and I told him about Bonzo. I said I’d never seen another drummer anywhere near as dynamic.”

Jimmy had already sounded out other drummers. He’d been interested in B. J. Wilson, whom he had met while playing on the Joe Cocker session, but he was contractually bound to Procol Harum. Clem Cattini, Jimmy’s frequent sessionmate, couldn’t be torn away from the windfall of steady studio work. “We definitely approached Aynsley Dunbar,” Peter Grant said. Dunbar had the right kind of pedigree, having played with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers and the Jeff Beck Group, but he considered the Yardbirds “old news . . . a step backwards, not forwards,” and was headed to a gig with Frank Zappa in the States before forming his own band. This drummer friend of Robert’s—Bonzo, Plant had called him—Jimmy remembered the incredible sound he’d delivered on the Band of Joy demo. It was enormously attractive to him.

“When I saw what a thrasher Bonzo was,” Jimmy said, “I knew he’d be incredible. He was into exactly the same sort of stuff as I was.” Jimmy’s excitement was contagious. Robert said, “I hitched back from Oxford and chased after John, got him on the side, and said, ‘Mate, you’ve got to join the Yardbirds.’”

The Yardbirds? Really? John Bonham wasn’t impressed. He had a steady gig with Tim Rose, an American singer-songwriter who’d been part of the American Big Three with Cass Elliot (as opposed to the band from Liverpool with the same name) and now performed almost exclusively in England. Besides, Bonham was being courted by both Joe Cocker and Chris Farlowe. What did he want with a group of has-beens like the Yardbirds?

Jimmy Page wasn’t deterred. On July 31, 1968, he popped into a Tim Rose show at the Country Club, a cabaret in West Hempstead.

He’d been around great drummers throughout his professional life, but he wasn’t prepared for the sound John Bonham put out. It was enormous, explosive, but a controlled explosion. This guy was unbelievable, the best drummer Jimmy had ever encountered. At one point, John stepped out for a five-minute drum solo, and Jimmy almost came out of his socks. “I’d never seen anyone quite like Bonzo,” he recalled. “That was it, it was immediate. I knew that he was going to be perfect.”

_______________________________________

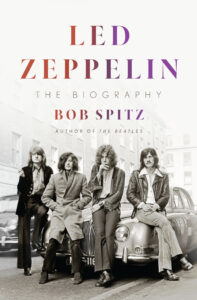

From Led Zeppelin: The Biography by Bob Spitz, to be published by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Bob Spitz.

Bob Spitz

Bob Spitz is the award-winning author of the biographies Dearie: The Remarkable Life of Julia Child and The Beatles, both New York Times bestsellers, as well as seven other nonfiction books and a screenplay. He helped manage Bruce Springsteen and Elton John at crucial points in their careers. He’s written hundreds of major profiles of figures, ranging from Keith Richards to Jane Fonda, from Paul McCartney to Paul Bowles.