The Legal Fight That Ended the Unjust Confinement of Mental Health Patients

Ayelet Waldman on the Landmark Case O’Connor v. Donaldson

In 1975, O’Connor v. Donaldson finally and firmly established the right of people with mental health disabilities to due process protection under the Fourteenth Amendment. In his ruling, Justice Potter Stewart held that “a state cannot constitutionally confine, without more a nondangerous individual who is capable of surviving safely in freedom by himself or with the help of willing and responsible family members or friends.” The decision transformed the status of people with mental health disabilities and of mental hospitals in the United States. According to Bruce Ennis, the singularly idealistic and devoted New York Civil Liberties Union attorney who argued the case before the Supreme Court, in an interview he gave to the New York Times on the day the opinion was issued, the result of the ruling was that “mental hospitals as we have known them can no longer exist in this country as dumping grounds for the old, the poor and the friendless.” To those of us who came of age after the civil rights movement, the facts of the case are boggling, compelling, and enraging in equal measure.

Thirteen years before the hospitalization at issue in the case, the plaintiff, Kenneth Donaldson, voluntarily checked himself into a psychiatric facility, an experience he describes in his book, Insanity Inside Out: The Personal Story Behind the Landmark Supreme Court Decision (1976). During this first hospitalization, Donaldson was by his own account a troublesome patient. He resented being forced to work as a dishwasher and scavenge his dinner from the discards on the staff plates. His grumblings about this and other injustices may well have been part of the motivation for referring him to electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), at the time an agonizing treatment that ward attendants and clinicians sometimes used as a punishment. Donaldson was strapped down and tormented with ECT twice a week. After 23 “treatments,” he was finally released.

Following this initial hospitalization, Donaldson was sluggish, hypersensitive, and, for a short period, impotent. He also became understandably suspicious of mental health professionals. As time passed, he began “writing letters to important people. These letters were suggestions, freely given with no expectation of reward other than the feeling of having done one’s part.” So (possibly) a crank. As a result of these letters, he claims in his book, he was subjected to a campaign of harassment by unknown individuals. “My papers were ransacked in my desk drawer and there was cigarette smoke in the room, though neither the maid nor I smoked.” So (possibly) paranoid. He changed his name and then changed it back. He moved over and over again. He had a brush with the law. But all along, he worked, he went to adult education and job training classes, and he raised and supported his family, though he eventually got divorced. Moreover, he was never violent. In fact, those who knew him reported that he was a gentle man.

Finally, in 1956, he moved to Florida to stay temporarily with his parents. Something went wrong during this visit, and Donaldson’s father called the police and had his son arrested. It’s unclear why Donaldson’s father made that initial phone call or why he refused ever to support his son’s release. Donaldson writes of having told his parents that he had written an autobiography and sent it off to a publisher. Perhaps that struck his father as delusional behavior. There is evidence that Donaldson expressed to his parents his belief that he had been poisoned by enemies before moving to Florida. What is not alleged was that Donaldson was aggressive or violent to his parents, to himself, or to anyone else. At any rate, his father made the call, Donaldson was arrested, and eventually, after a single, short hearing, he was confined to Florida State Hospital.

The jury found that the doctors had unjustifiably withheld psychiatric care from Donaldson, including grounds privileges.

Donaldson’s greatest misfortune was that once confined to the hospital, he came under the control of a psychiatrist named J. B. O’Connor. At the time of Donaldson’s commitment, O’Connor was assistant clinical director of Florida State Hospital. Eventually he was promoted all the way to superintendent. O’Connor seems to have borne Donaldson a grudge, perhaps because the patient had become a Christian Scientist and thus refused treatments like the ECT that had made him so miserable during his prior hospitalization. Donaldson remained confined in Florida State Hospital for the next 15 years, under the thumb of O’Connor and staff physician John Gumanis. He spent much of that time in an open ward with 60 other men, a third of whom had been charged with crimes. During those long years, he was seen for no more than a total of three hours by a psychiatrist, and even those few hours were devoted to administrative rather than therapeutic topics and tasks.

Again and again Donaldson petitioned for release. A variety of individuals, agencies, and doctors were ready and able to take on his outpatient care and even to have him live with them. These requests were always denied. O’Connor (falsely) insisted that Donaldson’s elderly and infirm parents were the only ones to whom he was legally permitted to release him, though by then, Donaldson was in his 50s. O’Connor gave lie to his claim by never approaching the Donaldsons to ask if they would support the release of their son.

Eventually Donaldson’s predicament caught the attention of Morton Birnbaum, a physician, attorney, and advocate for people with mental health disabilities who had long argued, including in the opinion pages of the New York Times, for the articulation of a constitutional right to adequate treatment. Birnbaum filed suit on his behalf, bringing in Bruce Ennis of the New York Civil Liberties Union. Ennis, like Birnbaum, was a vigorous advocate on behalf of people with mental health disabilities and had won a number of cases, of which he hoped Donaldson’s would be the culmination. The suit charged O’Connor, Gumanis, and others of civil rights violations, specifically the intentional and malicious deprivation of Donaldson’s right to liberty as guaranteed by the Civil Rights Act of 1871 and the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

Even as the suit was being filed, O’Connor retired. When word of the suit reached the new acting superintendent of the hospital, he and his staff first threatened to return Donaldson to a locked ward, and then, after pretrial rulings in Donaldson’s favor, suddenly released him. The case, however, continued to a jury trial.

At trial, O’Connor’s behavior toward Donaldson so shocked the conscience of the jury that they granted punitive damages against him and another psychiatrist. Among other things, the jury found that the doctors had unjustifiably withheld psychiatric care from Donaldson, including grounds privileges designed to teach independent living and occupational therapy.

The few budgetary dollars directed toward mental health are most often spent not on the sickest among us but on the “worried well.”

O’Connor appealed the ruling, and the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit affirmed the jury’s verdict. In response to O’Connor’s claim that he had acted in good faith, the court found, among other things, that he and the other defendants “wantonly, maliciously, or oppressively blocked efforts by responsible and interested friends and organizations to have Donaldson released to their custody.” The court also granted the right for which Ennis and Birnbaum had long advocated, ruling that if a patient is confined because he needs treatment for mental illness, and not because he is dangerous, due process demands that treatment actually be provided. Involuntary confinement can only be justified by such a quid pro quo.

After this unequivocal victory, O’Connor once again appealed, this time to the Supreme Court. Ennis, who would eventually go on to become the ACLU’s national legal director, had never before argued before the Court and later confided to friends that he spent the week before the argument vomiting from nerves. However anxious he may have been, the novice won a profound Supreme Court victory. Though unlike the Fifth Circuit, the Court did not create a constitutionally guaranteed right to treatment, they ruled that Donaldson’s prolonged incarceration was a violation of his right to liberty.

As a result of Donaldson’s case, state governments were compelled to enact statutes limiting involuntary civil commitment and creating mechanisms for periodic review. No nondangerous person would again be (legally) deprived of his liberty for decades, years, or even weeks and months at a time.

And yet it’s hard not to view this victory, though life changing for people with mental health disabilities and system changing for the institutions that had previously incarcerated them without reasonable recourse, as a partial one. What might have happened if Birnbaum and Ennis had been able to convince the Supreme Court to pair its Fourteenth Amendment ruling with a finding of an affirmative right to treatment? As it stands, the closure of most of the nation’s hospitals for people with mental health disabilities did not result in the creation of a well-funded system of community treatment or with increased resources for services like supported housing, job training, drug treatment, or family and parenting counseling. Furthermore, the few budgetary dollars directed toward mental health are most often spent not on the sickest among us but on the “worried well,” who are easier, cheaper, and more pleasant to treat, leaving the truly affected to cycle in and out of emergency rooms and short-term civil commitments.

Large numbers end up in jails and prisons, which have now become the warehouses of people with serious mental illnesses, where what is most often meted out is punishment and brutality rather than treatment. By conservative estimates, between 6 and 16 percent of the US prison population lives with severe mental illness, and the numbers are far higher when less serious mental illnesses and the illness of drug addiction and dependence are included in those figures. It is, however, no surprise that we have failed as a society to prioritize the needs of those of us with mental health challenges. Many of us respond to those we view as mentally ill with fear, disgust, and judgment rather than compassion. There are myriad reasons for this intolerance. Deeply embedded prejudices against those we view as less than fully human are as integral to the American character as the fantasy of “rugged individualism,” and the most severely mentally ill among us fall neatly into the category of despised other.

There are those of us, however, whose prejudice is a result of the anxiety of over-identification rather than fear of the other. As a high-functioning person with a mood disorder who has written openly about her mental illness, I found myself reading Kenneth Donaldson’s case and personal account with an eye toward drawing a distinction between him and me, as if to reassure myself that I wouldn’t ever have fallen into such a circumstance. I latched on to his various expressions of seemingly paranoid delusions with a sigh of relief. I’m not crazy like that, I thought. Am I?

It’s true I’ve never been hospitalized, but I came of age in a post–O’Connor v. Donaldson world. Were I of my grandparents’ generation, it’s entirely possible that my occasional bouts of suicidal ideation would have resulted in commitment, and once committed, I, like Donaldson, might have found it all but impossible to convince the arbiters of my incarceration that I should be freed. Moreover, and most important, as a white person of privilege, the system is inclined to trust and believe me, though gender can mitigate that privilege. A woman of color without my resources might even now struggle to convince a court of her “nondangerousness” to herself, if not to others. In the face of these realities, I find solace in the efforts of the ACLU and its lawyers to demand dignity and the protection of the Constitution on behalf of all of us, including—especially—those least likely to be deemed worthy of it.

————————————————

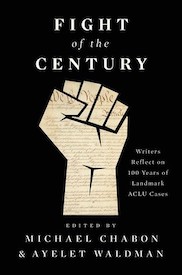

Excerpted from Ayelet Waldman’s essay published in Fight of the Century: Writers Reflect on 100 Years of Landmark ACLU Cases by Viet Thanh Nguyen, Jacqueline Woodson, Ann Patchett and others. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher, Avid Reader Press. All rights reserved.

Ayelet Waldman

Ayelet Waldman is the author of the memoir, A Really Good Day, as well as of novels including Love and Treasure, Red Hook Road, and Love and Other Impossible Pursuits. She is the editor of Inside This Place, Not of It: Narratives from Women's Prisons, and with Michael Chabon, of Kingdom of Olives and Ash: Writers Confront the Occupation and most recently, Fight of the Century.