That morning, hours after the cock crowed but before the townhall bell chimed eight, Bridey mounted narrow steps leading up from the kitchen, holding tight to the fluted handles of a silver oval on which Mr. Hollingworth’s breakfast quivered. Serving gloves weren’t insisted upon at Hollingwood as they were in the big houses on Fifth Avenue, where a friend from home worked, but Bridey sometimes wore them anyway—it spared prints on the silver, which saved time in the long run; the trays and pouring pots needn’t be polished so often.

Mr. Hollingworth’s breakfast was meager fare compared to the morning feasts she and Nettie used to cook up: blood sausages and custards, fruited popovers and muffins, eggs poached and scrambled and over easy or hard, depending on how he and his four children preferred them that day. But that was years ago, when the children were children, and breakfasts were rollicking starts of days in the dining room instead of quiet meals for an invalid who spent most of the time in bed.

A poached egg on toast is what she was carrying now to Mr. Hollingworth, along with a pot of coffee and a pitcher of cream she’d skimmed from the top of a bottle left this morning by the Byfield boys who’d taken over their father’s milk route. The bread was rack-toasted, despite the newly acquired electric toaster, which she hid in the pantry so it didn’t rebuke her. Sarah, the eldest, had brought it back from a traveling exhibition of housewares in Hartford, but Bridey didn’t trust the contraption, convinced that its complicated workings couldn’t be depended upon to produce the shade of toast she was after and, even more important, couldn’t be depended upon not to electrocute her. She’d racked toast on a fire for almost all of her thirty-four years. What would be the advantage of doing a task differently when it was one she had mastered and could do by hand without thinking? The electric cream separator, from the same exhibition, sat next to the toaster, both shrouded by covers that shielded them not only from dust but from Sarah’s notice should she wander into the pantry, an unlikely occurrence.

Bridey appreciated electrification in moderation. The house had been electrified ten years ago, soon after she’d stepped off the boat from the west country of Ireland, where electric lights were unheard of and they got along fine without them, thanks very much. Now, she appreciated being able to sew or read at night, which was hard to do by the flickering light of a candle. She sang the praises of the electric icebox. But Americans believed that if a thing was good, much more of a good thing was even better. Electric irons, electric sewing machines, even electric lighters for men’s cigars—Bridey couldn’t see the need for any of these, though Mr. Tupper, the electrician, assured her that such laborsaving devices were already proving indispensable to housekeepers.

A bell sounded in the stair corridor. The rear kitchen door. Bother. Bridey stepped backward and, careful to keep the tray in balance, turned and descended the steps. She set the tray on the counter, covered it with the silver dome, removed her gloves, and crossed the kitchen to open the door.

There, on the gray-painted porch, stood Mr. Tupper. It was as if he’d heard her maligning his work in her head.

“Come in, come in.” She swung the door wide to welcome him warmly, feeling a need to make up for the offense.

Mr. Tupper took off his cap as he stepped inside and set down his toolbox on the wide pine-board floor. “The Canfields were top of my list today, but they have guests stopping, so I’m here to replace your duals if it suits.”

“That would be grand,” said Bridey, pulling the door closed behind him. The sparrows were cheeping like chickens today. Yesterday, the door had been left ajar and one of them had flown in and it had taken her a mortal hour to shoo it out of the house.

“Americans believed that if a thing was good, much more of a good thing was even better. Electric irons, electric sewing machines, even electric lighters for men’s cigars—Bridey couldn’t see the need for any of these”When Mr. Tupper electrified Hollingwood, Mr. Hollingworth, like most home owners in Wellington, had prevailed upon him to convert existing gas fixtures to duals. Duals were lit by both electric lines and gas so that if electricity had turned out to be a passing fad, the lamps could be reverted to gas without the expense of calling Mr. Tupper again. Now it was clear that the invention had caught on and people were going all electric for safety reasons. Duals were proving to be temperamental. Last month, a leak of gas from a dual had caused a house just off Main Street to burst into flames. Mr. Tupper was so busy, it took months to get an appointment with him.

Today was far preferable to the December date marked on the wall calendar. It was still October. The holidays were a good ways away and whatever mess was about to be created would be certain not to interfere with holiday houseguests and entertaining. What’s more, Sarah and Edmund were abroad now, which meant they’d be spared seeing the mess that inevitably resulted from a visit by Mr. Tupper. Sarah became nervous when things in the house had to be changed.

Hollingwood had been built by Sarah’s grandfather, a governor of Connecticut who had drawn the plans for the house himself, which accounted for why the house wasn’t like any Bridey had seen. It was the biggest house in town, built with stones mined from local quarries that weren’t around anymore. The house looked to Bridey like a house in a fairy tale. It rambled this way and that, with long hallways and bow windows and several porches and sunrooms and a four-story octagonal turret. The windows at the top of the turret were arched and color-stained like church windows and whenever Bridey went up there to sweep up dead flies or dust the old telescope that nobody used, she stopped a moment to gaze through the colored panes, taking in the holy beauty of the field and the lake and the evergreens bordering everything, like a backdrop.

Bridey offered Mr. Tupper tea and a scone still warm from the oven and he ate efficiently, standing up at the worktable, careful to keep crumbs from falling onto his beard. As he dunked the scone into the teacup, he apologized for having to cut a hole in the wall. His work would damage the wallpaper, he said, which would have to be replaced. The thought of that made Bridey wonder if she ought to put him off after all. Perhaps she ought to consult Sarah, but Sarah was in Italy with Edmund on an extended lecture tour of the lake towns to celebrate their wedding anniversary. Their sixteenth. They’d married the summer after Bridey came to Hollingwood, and had her coming here really been so many years ago?

Sarah was the only one of the children who lived at home now. She’d returned to Hollingwood with Edmund soon after they married, having discovered that two Mrs. Porters in a house was one too many. Sarah was educated in many things (politics, painting, gardening) but left on her own, Bridey guessed, Sarah wouldn’t be able to boil an egg. Sarah was always seeking happiness afar, in every place but home, though that was where she was certain of finding it.

To Bridey’s mind, Vincent had suffered mightily because of this. Bridey, always alert to the boy, had spent years trying to relieve his suffering due to his mother’s inattention to him and it saddened her to know that she could not relieve it altogether. But now—Vincent wasn’t a boy anymore. He would be eighteen next birthday and how lucky for him, for all of them, that the Great War was over so the prospect of his being sacrificed for it needn’t be contemplated.

*

If Bridey turned Mr. Tupper away, it would be weeks before he came back, then it would be Christmas, a season of parties and celebrations, and it wouldn’t do for the front hall to be in a state. As Mr. Tupper finished his scone, Bridey went down to the basement and came back with old sheets from the rag bin. She’d learned the hard way about covering the furniture.

She led Mr. Tupper through the butler’s pantry and, with an elbow (her arms were full of the sheets), pushed the glass plate on the door panel, swung through the door, and took him left past the linen closet so as not to lead his work boots across the good dining-room rug.

As she turned into the hallway, she saw the scrolled brass arms of the dual to be replaced. Bridey hated to think of harm to the wallpaper beneath it. But there was a good wallpaper man in town now, and the decorator from France who’d hung the paper originally had had the foresight to leave an extra roll in the attic.

Mr. Tupper helped Bridey draw sheets over chairs and tables in the hall, then Bridey returned to the kitchen, touched the silver pot to make sure it was still warm (Mr. Hollingworth didn’t take hot coffee, due to sensitive teeth), slipped on the gloves, lifted the tray, and again mounted the stairs.

As she rounded the first landing, the hall shook with a great pounding and Bridey was visited by a terrible vision. Mr. Hollingworth’s bedroom was just above the spot where Mr. Tupper was working, and Bridey imagined shifts in the old wall causing the ceiling above it to fall and then Mr. Hollingworth’s floor crashing through and there would be Mr. Hollingworth, sliding down to the front door, still in his bed.

To steady herself, Bridey kept her hip against the wooden rails that ran along the top of the landing. It was a habit acquired long ago to keep from falling back down the narrow stairwell. The hallway was dim in the service quarters where only she lived now. When Nettie left to get married, Bridey hadn’t taken her room, even though it was larger. She stayed in her little room at the top of the stairs with the low ceiling and a window that looked out on the lake. She liked it there. She liked the light.

“Mr. Hollingworth’s bedroom was just above the spot where Mr. Tupper was working, and Bridey imagined shifts in the old wall causing the ceiling above it to fall and then Mr. Hollingworth’s floor crashing through and there would be Mr. Hollingworth, sliding down to the front door, still in his bed.”Last year, Mr. Hollingworth lived in Nettie’s old room, moving temporarily from his bedroom to Nettie’s because hers was a north room and the darkest. At times, even the slightest light hurt his eyes. Bridey had run up drapes in the sewing room for him, heavy velvet curtains that Nettie, on a visit from Massachusetts, smiled to see—their formality so out of place in a servant’s bedroom.

As Bridey crossed from the service hall to the bedroom wing, the pounding in the front hall became louder, and then came a crunch and the sound of falling plaster, by which she knew that the wall had been breached. Bridey was glad that Sarah—who felt any harm done to the house as a blow to herself—was spared this.

Bridey tapped with the toecap of her shoe, seeking the step up. She would tell Mr. Hollingworth that the egg was newly laid by Thisbe. Thisbe was the best layer in the henhouse, her eggs always firm and delicious. Was it an egg from Thisbe? Bridey couldn’t recall. She’d gathered the eggs yesterday, not today. But old men, like small boys, needed reasons to believe what you wanted them to believe. Mr. Hollingworth’s appetite—what was left of it—was best in the morning. He’d barely touched his dinner last night. He had to eat to keep up his strength. She wanted to make this meal as appealing as possible to him.

To that end, Bridey had prettied the tray. A picture postal from Sarah had come in the morning’s mail, sent from a town with an unpronounceable name. The town was built on a mountain and looked made of toy blocks. She’d propped its painted portrait against the bud vase that held a purple anemone, the last flower the cutting garden gave up.

She hoped Sarah had remembered to send a postal card to Vincent at school.

It was Vincent who had named the hen, a few years ago, the summer before he went to school across the lake. How seriously he’d prepared himself for Trowbridge, lifting barbells and eschewing white bread, adhering to a new eating regimen to build himself up.

His incoming school assignment had been to translate the story of Pyramus and Thisbe from Latin to English, and Vincent, after poring over a book in the porch off the library, had regaled Bridey with the tale of two young lovers kept apart by their families. It was all she could do to hide her brimming eyes by training them on the needle she was using to letter one of his handkerchiefs; she had to bite her tongue to keep from telling him the story it reminded her of.

*

She sang out as she always did upon approaching Mr. Hollingworth’s room.

“Your breakfast, Mr. H. Our Thisbe did her best for you this morning!”

The door was kept ajar and she pushed it gently with her elbow, already drawing in her mind the shape of the coming day. She would get Mr. Hollingworth properly propped on his pillows, taking care to keep his chest upright to avoid the danger of food falling into his windpipe, and while he was eating and reading papers magnified by a hand glass as big as his head, she’d go downstairs to the pantry to finish mixing beeswax and vinegar and then set to polishing the wood in the library. Friday was cleaning day. This schedule—Monday for wash, Tuesday for ironing, and so forth—was the same one she’d learned back in the class on practical housekeeping at St. Ursula’s. More and more houses were shaking off this old system in favor of letting housekeepers decide for themselves what to do, but Bridey kept to the old schedule, finding that it allowed her to do the work most efficiently, especially important now that there was only one person left in the house to do it.

The sheets didn’t stir. How could he have slept through the noise from below? As she neared the bed, she guessed that the extra sleep would be good for him. He slept little these days; he complained about the sleeplessness almost as much as the pain. Maybe Young Doc had given him a sleeping draft when he’d come to mix his dosages last night. The medicines were a new treatment he’d started giving Mr. Hollingworth after Old Doc died last year. It seemed to be working.

She settled the tray on the bedside table. His head was turned to the wall. Perhaps he’d taken sick in the night. Had he acquired a fever? She stepped forward to feel his forehead and when she touched his skin, she felt a coldness, a lack of charge, and when she bent over his face and saw his staring eyes, she apprehended—first in the hairs on her forearms, then in the hairs on the back of her neck—that Mr. Hollingworth wasn’t sleeping. He was dead.

She drew back suddenly, knocking the tray off the table, sending the plate and pot and creamer and vase clattering to the floor.

“You all right, Miss Molloy?” Mr. Tupper called from downstairs.

Bridey didn’t answer. She couldn’t believe Mr. Hollingworth was gone. The fits of blindness had ceased. Mr. Hollingworth had regained some energy, enough to take a constitutional around the house with her every so often. He’d improved enough for Sarah and Edmund to go on their long-planned anniversary trip. But now—

Bridey sank to her knees, crossed herself, and prayed, gazing at the man he had been. Mr. Hollingworth had been kind to her. He had been a kind man. He had taught her to swim. He had saved her life and the life of her son.

“She settled the tray on the bedside table. His head was turned to the wall. Perhaps he’d taken sick in the night. Had he acquired a fever? She stepped forward to feel his forehead and when she touched his skin, she felt a coldness, a lack of charge”She heard Mr. Tupper’s tread on the stairs, then in the hallway. She turned to see him bowing his head. Mr. Tupper was a big man. His head reached almost to the top of the ceiling, but he wasn’t bowing his head because of that.

“God rest his soul,” he murmured.

Bridey went to the window and drew back the curtains. She lifted the sash, just in case it was true that an open window eased the flight of the soul.

She turned back to the bed and pulled the sheet over Mr. Hollingworth’s face. The sheet was splattered with coffee, but that didn’t matter. She gathered what had been dropped, returned what she could to the tray, and asked Mr. Tupper to help her make calls. She was afraid of the telephone.

Watching her step as she balanced the tray she carried, she led Mr. Tupper down to the telephone table, a little round pedestal under the stairs, and he lifted the receiver and asked the operator for Young Doc. Doc was at the hospital now, but his office girl would give him the message.

She then told Mr. Tupper to ask for Vincent’s school. For Hannah’s bridal home in Litchfield. For Benno, who would be at the factory.

Mr. Tupper spoke through perforations in the receiver to the operator, and after he did this, each time, he handed Bridey the receiver, which she held at a distance as she enunciated words carefully, speaking as if to someone almost deaf.

“He’s gone!” she shouted. “Come home.”

Rachel lived in France. Both she and Sarah would have to be cablegrammed. She asked Mr. Tupper could he go to the post office to send word to Sarah and Rachel. He could. She wrote down numbers for him, from a book.

Bridey had to work on keeping her thoughts together; they were running all over, like headless chickens.

After Mr. Tupper left, she heard Young Doc’s Packard come up the drive. She was in the kitchen, at the sink, washing the breakfast things that hadn’t broken. When she looked through the window and saw Young Doc getting out of his car, she left the kitchen, wiping her hands on the hem of her apron, but he was already coming through the door, without knocking, which was unusual for him. “When did it happen?” he asked her.

“I found him just now, this morning,” she said.

She glanced at the clock on the hall table. It was near nine. Vincent was probably getting the news from the headmaster. He’d be home soon.

Something about the arrangement of Young Doc’s features wasn’t right. She’d expected compassion. Instead, he looked angry. As if she had done something wrong. Had she done something wrong? She couldn’t imagine what it could be. She always followed exactly the routine he’d set out for her, administered the dosage of medicines kept in the fireplace cabinet, mixed fresh every night and left for her in a tiny glass tumbler.

After taking off his hat but not his coat, Young Doc bounded up the spiral stairs. What was his hurry? Perhaps he doubted Bridey’s pronouncement. That Mr. Hollingworth might not be dead hadn’t occurred to Bridey, but now she supposed she could have made a mistake. And wouldn’t a mistake like that be a happiness to discover? But her heart remained heavy. She didn’t think she’d made a mistake.

Young Doc had a boyish manner. Old Doc had been the family doctor for years but now Old Doc was gone and Young Doc had taken over. She guessed he’d be Young Doc for the rest of his life.

When she came into Mr. Hollingworth’s room, Young Doc had opened the old man’s nightshirt and was pressing a stethoscope to his chest. Bridey flinched, feeling the cold of that disk. But of course, Mr. Hollingworth couldn’t feel it now.

Young Doc rose from the bed and turned toward the window, putting the stethoscope back in his bag. Bridey moved to rebutton Mr. Hollingworth’s nightshirt. It was then that Mr. Tupper came into the room.

“There weren’t enough numbers. Postmistress says there’s a number missing.”

Mr. Tupper’s eyes went to Mr. Hollingworth and fixed on his right arm, which was flung over the sheet, his hand drooping over the side of the bed.

“If I didn’t know better, I’d think the poor man had been poisoned,” he said.

“What?” said Bridey, startled.

Mr. Tupper approached Mr. Hollingworth and took up his hand.

“White lines in the nail bed. They taught us in training to watch out for that. Arsenic exposure. Green paint and wallpaper are mixed with it, you know.”

Bridey leaned closer. Faint white lines arced over the nail bed. Why hadn’t she noticed those lines before?

“You’re a doctor now, are you?” said Young Doc, turning.

Mr. Tupper flushed and looked away, toward the window.

Young Doc continued. “The technical term is leukonychia striata. Its appearance can indicate arsenic poisoning, yes, but also a multitude of other conditions . . . liver disease, malnourishment.”

Young Doc looked at Bridey.

“Miss Molloy, have you been withholding nourishment here?”

“No, indeed!” Bridey said. But she recalled Mr. Hollingworth’s lack of appetite lately, and perhaps she ought to have been more forceful in urging him to eat. Was her failure to insist that he eat more to blame for his death?

Mr. Tupper returned his gaze to the doctor. “The day Miss Molloy withholds food from a man is the day turtles sing,” he said and chuckled, so as to make light of a serious thing. But—Bridey was shaken.

“Come, Mr. Tupper, let’s find the right number.” She was overcome with wanting to leave the room and felt free to do so now that Mr. Hollingworth was rebuttoned and decent.

She let Mr. Tupper go first out of the room and was made to wait just outside the door while he stopped to adjust the seat of a wall sconce he’d installed years before. Bridey, standing in the well of a hall turn, saw the doctor open the high cabinet by the fireplace. It was where the medicines he mixed were kept. He took the blue bottle and pushed the cork down tight into its neck. He jammed the bottle into a pocket of his coat. The medicine in the blue jar was as precious as gold. Another patient would need it.

Bridey turned from Mr. Tupper and went down the back stairs and through the kitchen to the telephone table; she opened its drawer and found the book. She met Mr. Tupper in the kitchen, gave him the number, and unlocked the front door for him. Getting to the post office was quicker by way of the front.

She heard the doctor come down the spiral stairs and started in that direction to see him out. As she approached the hall, she saw the doctor reflected in the glass door of the china press. Why was he lingering in the hallway, glancing around furtively? Perhaps he was looking for her to give further instructions. But no. Now he stepped off the runner and moved to the wall. There was a hole where the dual fixture had been. She was glad to see it was a neatly cut square. Mr. Tupper did meticulous work.

The doctor patted his coat pocket, took out the bottle, held it up to examine it, then, to Bridey’s astonishment, dropped the bottle into the hole in the wall. She heard the glass tumble and hit the lathes before landing.

She stayed where she was, watching Young Doc’s reflection in a pane of the press as he took up his tall hat from the bench, put it on, and moved toward the front door. He stood a moment, pulling away the lace curtain to look out a sidelight. Then he reached for the brass knob, swung the door open, and closed it behind him—and Bridey went cold from the small of her back to the top of her head.

__________________________________

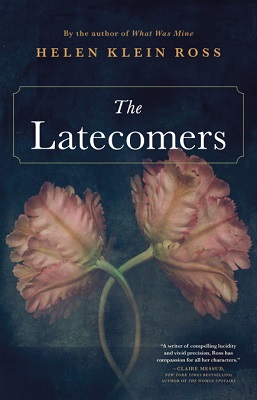

From The Latecomers. Used with permission of Little, Brown, and Company. Copyright © 2018 by Helen Klein Ross.