The Last Personal Essay About Race I Will Ever Write

Musa Okwonga on Realizing Racism Doesn’t Need to Be His Problem Anymore

Last week I spoke to two black men and one white man about being a black man in Berlin. One of the black men said: “Let me put a positive spin on it. Berlin is very international: it is also very white.” The other black man said: “As a black man in Berlin, people think that you are either an asylum seeker or an American. If someone sees you on the underground and you do not dress like you might be an asylum seeker, then they will wonder what part of America you are from.” The white man said, “I don’t want to say this but white German men see you as a kind of a threat. With the women.”

Well, I am neither an asylum seeker—unless you count the Brexit vote—nor am I American, and so I wonder how many passers-by I have confused during my short time in the city. I have been in Berlin for two and a half years now, having moved there from London to start afresh both professionally and personally. I’ve also been interested by how often I have been invited into the bedrooms of white heterosexual German couples—only as a concept, I hasten to add. A white German woman, who was then my partner, told me how white German men were fascinated that she had dated black men, and wanted to know all about the sexual experience she had had. “What are they like?” they asked her, as if our genitals were some exotic land to which only a few brave people were granted a visa. “Is it true what they say? Are black men bigger?”

Some of you might think that this kind of reputation is flattering, but I can assure you that it is not. Stereotypes like this—other than creating an intimidating level of hype around how you might be in bed—are frequently accompanied by more damaging prejudices. One afternoon, in one of my occasional bouts of romantic optimism, I logged onto Tinder. Despite this app’s notoriety for enabling the briefest of encounters, several of my friends had met long-term partners on there, so I thought I’d give it a go. After browsing—or, let’s be honest, swiping—for a while, I got talking to a French woman who worked in marketing for a cosmetics firm. She seemed nice enough at first, and then she informed me that she was only interested in black guys. Ah, I thought. There’s always an alarm when white women tell me that. What do they mean? That they like all of us? What is it about is that they like? She continued. She wasn’t from Berlin, she was only visiting from Paris. Ah, I said. She wanted to go wild, she said. She was seeing a different black guy each night. Could we have sex tomorrow afternoon. This was all a bit sudden, I thought. We hadn’t even had coffee yet. Did this make her a bad person, she asked. Well, no, I said, no-one judges straight men who do that. Well, I am judging myself, she said. The whole conversation was so awkward that we stopped talking after that.

A similarly weird thing had happened on a date a few months previously, when I met a Hungarian woman. A few minutes into our meal, she announced that, in her experience of dating black men, we fell very clearly into three categories: the African, the British, and the American. The African was more aggressive, more forceful; the Brit was somewhat more reserved, more shy; the American was more confident. Looking back, the date was pretty much over from that moment. Any time I said something which challenged her view of what black British men were like, I felt like cattle who had temporarily escaped their pen. Of course, the evening drew to an uneasy close.

I think the French woman and the Hungarian woman had something in common. Neither of them would simply allow a black guy just to be. They both had very strong ideas of what we would be like, and there was nothing I could do but disappoint them. The French woman, it quickly became clear, wanted to be overwhelmed by the brawn of a grunting black man, and was horrified I might actually want to date her first. The Hungarian woman wanted someone more confident, more assertive, but not too assertive. I think that going out with her would have felt much like living with an owner who is not quite sure their pet has been fully tamed.

*

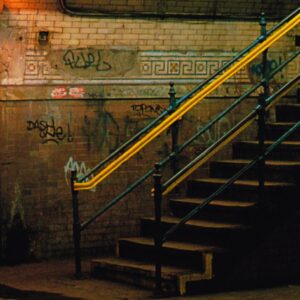

I think I had a mid-life crisis last November. I say mid-life crisis because in November I was 37 and most of the men in my family, so long as civil wars don’t get in the way, seem to live to about 75. I had a mid-life crisis because I finally realized that racism was something I could never outrun. It would always be there, at the end of my road or maybe even at the foot of my bed. I realized this one day when I was walking home, happily enjoying the latest song I’d bought on iTunes, and a white German woman shoved her friend into my path. I was almost thrown off my feet.

Why did you do that, I asked. Can you speak German, she asked me in German, which was the first sign. I can, I replied in German. Good, she said, that’s what we speak here, this is my country. (That was the second sign.) Your country, I said. Do you have a problem with black people? She shrugged. Are you a racist? I asked. Yes, I’m racist, she shrugged. So what? There are all kinds of racists. White racists, black racists, Turkish racists.

The exchange—I am not ashamed to admit—took my breath away. I won’t tell you the full story, because it’s exhausting to re-tell it here, and I’m tired. The short story is that it briefly shook me so badly I seriously considered leaving the city, just two years after I’d arrived there. This episode might seem minor by itself, but it had happened at the end of a few weeks which, when viewed as a whole, were uniquely traumatic. A 17-year-old black boy had his head kicked in by four neo-Nazis in an area little different to Kentish Town. One of my friends had been on a train with a neo-Nazi who had shown her his tattoos, a pair of SS lightning-bolts. Another friend had been pushed off her bike by an elderly white German woman. The neo-Nazi AfD party had just won 14 percent of the vote in Berlin. Donald Trump had just been elected. It felt like something was brewing, and I didn’t want to be in the city when everything came to a head. I mean, how comfortable did people have to be in their racism that a white woman could attack a tall black man in broad daylight? I was so, so close to moving away; closer than most of my friends truly understood. I spent the last few months of last year sizing up a couple of other European capitals. But I stayed, and I am glad that I did.

Last week, in the German countryside, I conducted the wedding ceremony of a couple who, within just a couple of years, have become some of my closest friends in the world. A few months before that, I signed a record deal in Berlin, my very first after about a decade of releasing my own music. I currently play football—not that well anymore, I must confess—for the best bunch of footballers I have known, a squad boasting 25 members from 14 different nationalities. I have befriended some of the most brilliant black creatives anywhere in Europe, a collection of poets, novelists, singers and painters. And I could have turned my back on all of this, just because of the culmination of a few weeks of racism in my new home city.

This is what racism does, you see. It constantly stops us, diverts us, interrupts us. It halts us at the borders of countries and of love; it makes us stand in the bathroom mirror and feel ugly, it makes us invisible when we want to be seen and visible when we do not. Racism exhausts us. It taunts us with the safety that’s always out of reach.

I called my younger sister a few months ago, when I was having my mid-life crisis. I asked her, when does racism stop? When does the age come when you can just relax—where you’ve earned enough or achieved enough or become respected enough so that you’re free of it? “It never ends, Musa,” she said. “It never does.”

That phrase was devastating at the time, but now it’s liberating. It’s not that I don’t still find racism upsetting: of course I do. It’s just that, from now on, it’s not my problem. Racism is not a peak I have to conquer, or a weight I have to lift. At the age of 37, with my mid-life crisis hopefully behind me, I’m not trying to impress anyone anymore. As far as possible, I try not to see myself as a black guy, or a black queer guy, or a poshly educated black queer guy. That’s someone else’s job, not mine. For the first time in my life, I’m trying to be Musa, and I’m succeeding more each day. And, in one of the best pieces of advice someone has ever given me, I like to remember what an old girlfriend once told me. “Not everyone is going to get you,” she said, “and not everyone has to. To some people, you’ll just have to be an enigma.”

I moved to Berlin because, for all its flaws, it was a place where misfits could fit in. And, everything considered, I was right. I’ve come to realize I may never be truly settled in one place, in the conventional sense. Maybe that’s something I’ve inherited from my parents, who were refugees from Idi Amin’s Uganda; the sense of not truly belonging. Whatever the case, it feels good, for as far as I can see into the future. In a life which has so often been defined by escaping things, it’s really nice to have stopped running.

Musa Okwonga

Musa Okwonga is a poet, author, sportswriter, broadcaster, musician, public relations consultant and commentator on current affairs, including culture, politics, sport, race, gender and sexuality. His music has been featured by The Sunday Times, Drowned in Sound and Knowledge Magazine.He is the author of two books on football, A Cultured Left Foot (Duckworths, 2007) and Will You Manage? (Serpent’s Tail, 2010)