A ride is all I ask; good company and bumming tales are what I have to offer. Thanks, buddy. Thank you, sir. Missouri? Sure. Tulsa? That’ll do just fine. He joined the denim brotherhood of drivers and bums at gas stations and highway turnoffs. Slow road climb to the ridgeline and back down. Unsettled skies of early summer, driver’s eyes on the blackening horizon, scanning for lightning bolts and funnel clouds. Prairie grasses, never plowed, home to rattlers and assorted other varmints. Joe Sanderson, great-grandson of wagonmen who traveled on rutted roads through these grasses, now following the sunset, sort of. Erect corn and swaying mustardy wheat catching the wind, car radios transmitting teenage anthems. I see a line of cars and they’re all painted black. Reverb, sitars and steel guitars. His first wired money would be waiting for him at the

U.S. Embassy in Panama, down in the umbilical cord of North America. After that he’d hotfoot it all the way to Tierra del Fuego. Dear Mom and Calhoun, he wrote from Mexico. Forty-four hours later, $8 and six car rides and a Mexican bus, and I’m in Tampico. Not bad, eh? I mean, for the educated bum, that is.

Drank beer with a Detroit boy clear to Tulsa, Oklahoma; gallons of beer with 3 Lawrence, Kansas, fellows who own a tavern there; short rides with a University of Missouri student, a Vietnam vet and a Negro driving a stationery company van; then a last ride, clear to Brownsville with a 50 yr. old man and a bottle of Scotch. Claimed his second wife was top Houston businesswoman, claimed also he’d been worth $1½ million in better days, lost everything, and hated the federal income tax with a passion, far more than he hated integration of the races. Huh?

Mexico slowly brought Spanish to his tongue. Huevos tibios: hard-boiled eggs. ¿Con salsa? ¿Con salsita? It doesn’t mean little salsa, but more like, With salsa, dear? A language full of little endearments like that. At the bus station he had a passable conversation with a Chinese Mexican guy named Félix Chuang.

“Estoy viajando a Panamá,” Joe said. “Después a Sudamérica. A Tierra del Fuego.”

“Un viaje réquete largo,” Félix said, and Joe loved the sound of that word. Re-que-te, which through a kind of linguistic osmosis he understood to mean “heck of,” as in “That’s a heck of a long trip.”

“El sol quema,” Joe said, pointing to his peeling arms. Réquete quema.

¿Cuántas horas a Mérida? By the time I get to Chile, I’ll be speaking like a native, seducing the señoritas with my fluent Castilian. ¡Qué bonito su pelo! With your looks, Sanderson, and Spanish on the tip of your tongue, the sky is the limit.

He sat next to Félix on a third-class bus following the Atlantic Coast of Mexico, rolling into Veracruz and into the oil fields and the Olmec country to the south. The bus stopped in a town with the unpronounceable name of Coatzacoalcos. Looking out the window, he saw a street half-flooded from a recent rainstorm, and a row of cement storefronts, and a woman standing before a cart stacked with fried cakes wrapped in paper, a boy sitting next to her on the curb. The woman looked twenty and forty at the same time, and had the elegant thinness that is born of perpetual motion and labor, although at this moment she was standing perfectly still, while at her feet her son was gathering pieces of discarded paper and folding them into boats and launching them across the black puddle before him. The boy had a fleet floating on the water, and his mother looked down just as a car drove by and made a wave in the puddle; the boats rose and fell, and the boy squeal-laughed at the miniature maritime scene he’d created.

An entire novel was unfolding in the frame of his window. I know what that boy is thinking: When is Mom gonna be done working? The mother looks down and turns up her lips. An entire novel that I’ll never know or write. The bus set off and Joe saw shoebox storefronts with hand-painted signs, and more faces, and he thought of all the interlinked stories in this street and city. He felt like a man walking into a forest where the stories were like spiderwebs strung between the trees: invisible filaments of narrative were sticking to him, but he could never hold them and know the full beauty of their structure, of their spider-spun art. The bus rolled into the countryside, into a landscape of yucca plants and swamps. More Mexico, más Mexico, más, más, más mysterious Mexico. México misterioso: the Indians, the Spaniards, the Chinese, oil derricks and walls covered with the oxymorons of government graffiti. Long Live the Institutional Revolutionary Party!

“No comprendo México,” Joe said to Félix.

Félix laughed and said, “Rulfo,” and he opened his suitcase and reached inside and produced a thin book. El llano en llamas. By a writer named Juan Rulfo, and Joe understood that Félix thought this book explained Mexico. Joe opened it, and of course the whole thing was in Spanish. With his dictionary Joe managed to understand the first sentence.

I am sitting next to the sewer, waiting for the frogs to come out.

Over the course of the next hour on the bus, Joe and his dictionary and his embryonic Spanish brain decoded a few more sentences, and Joe gathered that the narrator of the story was a boy who had been sent by his godmother to kill the frogs because their croaking was keeping her awake at night. Intriguing.

Joe returned the book when they reached Cozumel and his new friend got off the bus. “Gracias, Félix.” Joe was proud of himself for talking to Félix and reading a paragraph of his book. Really starting to get good at the whole Spanish thing. A short while later he reached a territory where his Spanish was useless, because the people there spoke the Queen’s English.

welcome to british honduras

British soldiers in long, loose-fitting khaki pants patrolled the streets with fixed bayonets and the slow, deliberate, feline strides of men expecting to be ambushed. In Belize City, Joe breathed the wet, smoky air that follows a tropical riot. Here and there, a looted building, the remnants of a half-hearted barricade of sticks and barrels. The British soldiers are a pasty-faced bunch of kids, and they look scared to death, Joe wrote home. He boarded a puttering old boat southward and arrived in the Guatemalan city of Puerto Barrios; here too he found troops on a war footing. A few days earlier a band of Marxist guerrillas had infiltrated the town and painted the graffito Patria o Muerte on the walls. Fatherland or Death, though Joe misunderstood it to read Patria de Muerte, Fatherland of Death, and he inserted this phrase in his next letter. Here I am, in the Fatherland of Death, and doesn’t that sound horror-movie scary. These were the same rebels who had taken up arms after the banana war that worried Milt all those years ago, but they were a small, hidden force, and Joe knew nothing about them. He traveled in a steam train southward and uphill, blasting a white mist into the groves of banana trees. At toy-size wooden train stations, old men in straw hats watched his train roll past. By the time he reached the capital, night had fallen.

The next morning, Joe emerged from a hotel near the main plaza of Guatemala City, stepping out into “the Land of Eternal Spring,” as the locals called it. The sky was, in fact, the richest and deepest blue he’d ever seen, as if Guatemala were the source from which all the blueness of the world’s skies was born. Mayan Indians walked about the city, many wearing sandals and ornate patterns of hornet-green and sunflower-yellow threads woven into their clothes, walking past the limeade stone of the National Palace, speaking in the odd constant clusters of their indigenous languages. He saw a black graffito that screamed, once again, Patria o Muerte, but the newspapers mentioned that all was calm since the army had lifted the state of siege a week earlier. I missed the major part of the riots in British Honduras by two days, Joe wrote home. Just like I missed the real action of ten thousand Mexican students rioting in ’58, the Festival rumble in Trinidad, and the Jamaican militia called out against the Rastas. Oh well, I guess I can’t be at all the revolutions. An idea took root in Joe’s bumming brain: Maybe one day he’d wander into “action,” events so dramatic and violent, that the publishable plot of a novel would present itself to him. Effortlessly. With Joe in a starring role, of course. A war, a revolution, an uprising, a coup. Something.

*

He entered a country called El Salvador. Named after Jesus, the nation was, appropriately enough, at war with no one. In the town of Sonsonate he sat on a bench in the town square, and was surrounded by the courtship rituals of the town’s youth. Lean this way, look that way. Boys with their fingers in their belts, girls with ice cream cones, group giggles, one boy’s bold march across the concrete square toward one girl. Puppy love. They are here, in the center of their Salvadoran everything, and I’m just a visitor. I would march across the square for . . . ? For Karen Thomas, if anyone.

He got a ride into a valley where the hillsides were covered with cornstalks and the trees speckled with vermilion coffee beans, and was deposited at a crossroads littered with piles of burning trash; a vortex of vultures circled overhead, gliding through the climbing pillars of sweet, sticky smoke. The vultures and their greasy wings transmitted a dark meaning he could not decipher. Avian augurs, summoned by unseen witches. A brand-new Chevrolet Impala passed, and the driver slowed down and stared at Joe. In El Salvador, the rich inhabited a smug bubble of comfort floating inside a universe of poverty, and the driver was perplexed by a blond man’s presence outside this bubble, standing next to a pile of smoldering garbage, no less. So he circled back and invited Joe to a bar in town; as they drank rum, he warned Joe how dangerous the roads of El Salvador were at night. Was all for continuing, but people in the town said that not only was the city itself unsafe, but the Pan-American Highway especially, Joe wrote home. Bandits, etc. The idea of being robbed didn’t faze Joe much: he was carrying a .22-caliber revolver in his backpack, a Smith and Wesson, having crossed four borders without a single customs inspector asking to see the contents of his U.S. Army–issue rucksack. He crossed four more with his gun undetected, and reached Panama.

The vessels passing through the Panama Canal seemed to offer the possibility of a cheap ride across one ocean or the other. Cruise ships and tankers floated past him in the canal’s bathtubs, following paths across the meridians of the world. None offered free passage, so he bought a ticket on a freighter headed to Colombia, and he arrived in the port city of Cartagena, and explored its old center, and saw sunflower-and-royal-blue colonial buildings and colonnades and ferns growing in the balconies. Parrots squawked inside the homes as he passed, the way dogs barked in Urbana neighborhoods when he strolled through. “¡Cua, cua, cua!” a parrot yelled. “¡Carajo!” He hitchhiked toward Bogotá, upward into thinner air, marveling at the serenity of Colombia and its serpentine highways. But the Colombians who rushed past Joe on the Pan-American Highway, where he stood with a raised thumb, saw a vision of a disturbing future. The rush of passing traffic lifted the loose strands of the gringo’s unbarbered blond hair, the frayed bottoms of his blue jeans. Here come the American hippies we’ve been hearing about, ready to share their addictions and excesses. Free love: unfettered, degenerate, and syphilitic. When he reached the equator a square sign announced with simplicity and understatement: linea equinoccial, lat. 0° 0. Made friends with a beautiful little “Brigitte Bardot” singer (radio, TV, nightclubs) and her “friend,” a professional wrestler (“El Incognito,” wears a hood like an executioner’s!), Joe wrote from Guayaquil, Ecuador. The singer cuts wonderful hair and makes a good cup of coffee and her friend is going to see if he can get me a few bouts with other mat-rats. Huh? What say? I see the headline: “Young Novelist Wrestles His Way Around World.” From the looks of the local fighters I’ll need brass knuckles and a pogo stick to win, however.

The singer and the wrestler told him to stay and drink in more of Ecuador, but he felt the pull of the south, and he moved quickly to depart for his next country, only to discover after some consultations with the locals that he had failed to obtain the proper visa before walking across the border from Colombia. Entered Ecuador illegally (so I found out today), he wrote home. But I met a fellow at a travel agency who promised to fix things up . . . He’s likewise going to write me the phony plane ticket I need to walk into Peru. These were the machinations to which good bums had to resort, because the laws of the world were not written for Illinois hitchhikers to drift across borders willy-nilly. He told his mother to write to him care of the United States Embassy in Santiago, Chile.

*

In Urbana, Joe’s letter arrived in the mailbox on a Friday afternoon, for his mother to find when she got home from work. Another country. Ecuador, with a spacecraft hovering in the stamp over said country. She didn’t want to open it immediately. Will I ever lose this sense of worry? She lingered at the door; the air was summer heavy. Mist clouds floated over the city, and an air conditioner hummed somewhere. Ecuador, he’s reached South America. Virginia stepped inside, retrieved her letter opener and removed Joe’s written pages. Dear Mom and Calhoun, he says. Nice he mentions Calhoun. He’s fine, eating well. Another pretty woman, a Brigitte Bardot this time. Another one! Like moths to light with him now. Where does he get this from? Not from his father. No Romeos in Kansas or Oklahoma. None. They call it charm. He could charm the pants, no the skirt . . . This is a skill, a quality. He means no harm, he means to care, but they don’t know, these girls. Wants me to remind Steve to send five hundred dollars to Santiago.

The words entered . . . illegally caused Virginia passing concern, though it seemed like the sort of problem her son routinely talked his way out of. If he kept moving he would stay out of trouble; it was the idea that he would join up with assorted agitators and prostitutes again that worried her the most. The following afternoon, a Saturday, she and Calhoun had the widow Annabel Ebert over for lunch. Calhoun cooked a meal for them on the grill. Annabel said her son, Roger, was in Chicago, starting a new job at the Sun-Times for the newspaper’s Sunday magazine. Roger had written some book reviews for the Daily News, and Annabel clipped them from the newspaper with pride. From success to success. Roger is a professional writer, my Joe wants to be a writer. Roger has the discipline to finish things and see them through, and he was wise enough, in Virginia’s estimation, to conquer small things first, starting with a story for his high school newspaper; unlike her son, who took on the biggest thing you could think of all at once, a novel, and had failed. Predictably. Again and again.

“I’m so excited for Roger, living in Chicago,” Virginia said. “I miss him. You’re so lucky Steve is here.”

“I am. And Joe: well, he’s being Joe,” Virginia said. “Where is he now?”

Virginia explained that Joe was headed to the tip of South America.

He’d been to about twenty countries so far, by Virginia’s count.

“He has a visa to go to Japan,” Virginia said. “He says he’s going to go all the way around the world.”

“Wow, that’s something,” Annabel said. “That’s really something.”

That night, Virginia took the letters from the shoebox where she kept them and looked at their stamps, the names of countries, the symbols of their currencies, their smudgy postmarks. Really something. She ordered them by the dates Joe had sent them. The first one from Tampico. The second one from Guatemala City. She numbered them. A week later, when the next one came, from Lima, Peru, she wrote a five in a circle on the envelope.

*

Joe’s bus followed sand dunes and the Pacific Coast for the final stretch into Lima. In the space between his eyes there was a compass, pointing south, as if he were a migrating bird obeying instinct. South was the only reason for his existence. Entering Lima, he saw wealthy white Limeños cruising in sexy Fords and Chevrolets, and the faces of the Inca carrying shovels and pushing carts, and he felt the anger and resentments between these opposing versions of Peruvian reality. In the center of Lima, he saw a stone-paved plaza, lemon-colored colonial buildings, a bronze conquistador, his equine mount. And in the rocky mountains that surrounded the city, he saw the concrete-and-brick Machu Picchus where the poor lived, and he sensed displacement, the retreat of rural villagers to an improvised city, as if fleeing a war, burning homes in the Andes. But there is no war, only the daily routine of work and family. Lima was endless, or rather, its boundaries were porous and undefined, and each time Joe traveled beyond its fringes to desert beaches and plains, the city came back to life again, as if Lima were a living thing sending out spores to conquer new patches of sandy soil. Finally, he escaped the metropolis, and hitchhiked toward Lake Titicaca, and when he reached its waters he found them surrounded by a rim of hills that were a bleached and powdery brown, white mountain peaks beaming majestically on the far horizon.

The buses here were cheap and he took another one into Bolivia. Road dust and shrublands and reed grasses the color of urine. Altiplano. High plain. Altitude, twelve thousand feet. He’d traveled from the center of North America to the center of South America, and now he entered a high-altitude dream where farm people lived in mud homes with mud-walled corrals to keep in sheep, goats and llamas, actual llamas, mystical creatures, long-necked and flapping their tongues. Women in woven shawls and long skirts and with thick calves, men with wool vests, children in their wake, scratching at the soil with sticks, making circles and ovals and squares. Their Altiplano faces began to melt in the darkness and the bus window now reflected Joe’s ungroomed mustache. Twenty-four years old. Prescription spectacles. The bus stopped at a crossroads with a lone light pole, an oasis of light in the desert dark, overlooking a cluster of travelers, a shack. The bus driver got off to stretch his legs, and Joe followed after him, stepping into the pool of light and a crackled road tarmac. Two dozen sets of eyes fell upon him.

The Aymara men and women who saw him were disturbed by the unexpected appearance of a European man in the middle of the night in the middle of the Altiplano, and by the way his pale skin and egg-blue eyes gleamed in the gray light. He was an alabaster apparition, an omen, and for several of the bus passengers he triggered memories of recent encounters with bad luck, the demons that haunted their lives on the shrublands and in the hilly city of La Paz. A rain-swollen river, a house-swallowing whirlwind, a traffic accident, a rampaging goat. The white ghost insists on traveling with us, among us, and hurry, hurry, bus, and get us to the city so that we can be free of him and his evil portent.

*

Supposedly, I’m writing a novel. But what is an adventure written on paper compared to the four-dimensional, full-color experience of a journey on the road with the rising sun, two snowcapped volcanoes and llamas bolting across the tracks? Again, the strange animals, small-headed; they turned to look at Joe as he passed. Being a writer isn’t just what you live, the places you see, the adventures that unfold before your eyes; it’s the old soul you become, the road-bum knowledge that seeps into your brain with each kilometer. He could begin to see the central fact, the lesson of the road. The big world is tied together by asphalt, sea lanes and footpaths, and everywhere you go humans are puttering away for more or less the same reasons. For family. Toil, till, harvest, over Peruvian potato patches and Illinois corn. The train entered Chile and his exhausted eyes glimpsed the Pacific, blue and infinite, waiting for him with seashells and mermaids and sand to heat his tired toes. Ocean thoughts lulled him to sleep, and when he woke up he was in Arica. At the edge of Arica he stood on the asphalt of the Pan-American Highway again, and stuck out his thumb. A mint-green Buick slowed down and stopped, and a harried woman in a blue evening dress stepped out and opened the door, and took the back seat, while the driver, a man with a cigarette drooping from his lips, gestured for Joe to take the front. “Voy a Santiago,” Joe said.

“¿Santiago? ¡Son mil quinientos kilómetros!” Yes, Joe’s next destination was fifteen hundred kilometers away, nine hundred miles, and he couldn’t wait to reach it. Letters from home were waiting for him at the United States Embassy in Chile’s capital, along with a check, hopefully. Joe hopped into the Buick, but before he could say “Gracias,” the driver and his female passenger began to argue; or, rather, they resumed the argument they were likely engaged in when they stopped to pick up Joe. “¡Tú!” the man yelled, and the woman replied, “¡No, tú!” and the woman reached forward, and removed the driver’s panama hat, and struck him with it, yelling, “¡Mentiroso!” until the car stopped. The woman got out, and as the driver turned the car around to head back to Arica, Joe said he would get out too; he found himself standing on the southbound side of the road hitchhiking, while the woman did the same on the other side. A north-bound car appeared and took the woman away, leaving Joe alone in an otherworldly landscape of dunes and gray cliffs, baking under the resurgent sun, expecting a spacecraft from Earth to land at any moment. Just as he was contemplating walking back to town, a Jeep with three nattily dressed men pulled up and stopped.

“Where are you going?” one of them asked in English. “Santiago.”

“We are too!”

They were all wearing sunglasses and grinning, and they smelled of alcohol, and they engaged Joe in a bilingual conversation. They were three whitish-blond Chilean brothers, headed back to Santiago after a road trip to Peru: towheaded boys that looked like Aussies, he would later write in a letter home. As the Jeep drove deeper into the desert, the two passenger brothers fell asleep in the open-air vehicle, hypnotized by the straight road and the empty desert; it was like a drive across Kansas, but with no thing living anywhere, except maybe the bacteria clinging to the beads of fog blowing in from the ocean. “Atacama!” the driver shouted. Not a single bug on the windshield, no roadkill on the asphalt. Nothing. A universe of umber sand, dead mountains. No towns or gas stations. Amusements only for the devotees of rocks. The Chilean passengers resumed their drunken carousing once they woke up, drinking red wine straight from a bottle. The driver took a swig too, and sped up, and when he did so the Jeep yawed, like an airplane being buffeted by crosswinds, the pickled torsos of his passengers swaying in unison. Bad suspension; my brother would sort it out in an hour.

For three days he traveled with the Chileans, stopping for roadside naps and meals. When they entered cities and towns and other settlements, they caught the stares of workingman Chile; of women tending to big pots on the roadside, and men in overalls, carrying wrenches and tools. When Joe and the three brothers entered the proletarian suburbs of Santiago, they found a city filled by the smoke of winter fires, and a haze that turned the massive Andes into a stained patch of sky on the horizon, the mere suggestion of a mountain range. And they saw graffiti that hinted at the coming class war: red stars, men carrying hammers and raised-fist symbols painted on brick walls, a rebellion of the black-haired against the blond and the fair, the chiseled Indians against the tall police and their polished black boots. Battles to be fought in the brick-lined alleys, in the warrens of shacks by the river, at night, by flashlight, with fire and stones.

Hitchhiked 1,500 kilometers with a wild bunch that somehow kept the Jeep aimed toward Santiago, Joe wrote home, when he finally reached the apartment where the Chilean brothers lived, on an entire floor of a building overlooking the national military academy. Traffic accident in the desert (smashed windshield) which cut up two of the Chileans—I came out unscathed. White wine to sterilize the wounds and my red handkerchiefs for bandages and we blasted away, drinking the balance of the wine. Drove steady except for breakfast by the sea and sidewalk steaks while a carpenter built us a new windshield. More wine the next day, enough that we kidnapped a penguin at a restaurant 200 kilometers from Santiago. Stayed overnight with the Chileans (Scottish mother, Swiss father), realizing the next day they weren’t just rich, but really repulsively rich. Got a good night’s sleep (1st horizontal sleep in 4 days) and some damn good meals the next day, then ducked invitations to stay on longer.

No more brie, thank you. I just couldn’t. The bacon was excellent. Just like home! He slipped away to the U.S. Embassy, where a small stack of envelopes was waiting for him, including some forwarded by the embassy in Panama. Steve had sent the precious funds, his flagpole money. Writing from Arizona, his father said a fellow scientist had named a new species of riffle beetle in Milt’s honor. Xenelmis sandersoni. His mother said it was a hundred degrees in Urbana. Joe wrote back: Any chance of mailing some August dust and sweat in exchange for a little Chilean snow?

He left Santiago, headed through crop fields and dormant vineyards, splurging with his flagpole-painting money on the relative comfort of a second-class bus. After many hours the land became darker and evergreen, and a stormy winter wind blew through the pine forests and the eucalyptus tree farms. He reached the port city of Puerto Montt. Leaving for Tierra del Fuego tomorrow a.m. by boat—a weeklong trip, he wrote home on August 30. People here tell me I “might” get treated to my first iceberg. Sounds outlandish, I know, but I guess I will be roaming fairly near Antarctica. His passenger ship sailed past an island where spirits were said to live in the trees, and around many others that were uninhabited but for seals and penguins, and he saw no icebergs but much snow falling on the waves, and on a gray and gloomy morning his ship docked at the pier in Punta Arenas. He found the cheapest lodgings in town and wrote home.

And so, a week later, here I are—The End of the World! Cold? Jesus Gawd! What looks like ice crystals drop out of the sky even when it’s cloudless, and talk about digging under the blankets at night—you betcha! He described the journey from Puerto Montt thusly: Quiet sailing. Rode third class, including meals, for $9.30, spending nearly all my time in the 1st-class lounge and bar (of course), drinking, swapping lies with the captain, beating everyone at chess, and in general enjoying the Mississippi River boat atmosphere at a pauper’s rate.

Hit town last night and got into a place called El Scorpion Nocturno—$1.80/day with meals. Of course, there were a few suspicious looking ladies wandering about, but I smiled innocently like a choir boy, bewildered that the thermometer has so little sway over virtue.

He tried to see if he could do a one-day bumming trip south out of Punta Arenas, on Chile National Highway Number 9. Several drivers passed him and his outstretched thumb and gave him perplexed looks as he stood on the edge of town. Finally a taxi driver stopped and asked. “¿A dónde va?”

“To the next town,” Joe said in Spanish.

“There is nothing,” the taxi driver said. “This is the last town, the last place in Chile where people live.”

“Where does this road go then?” “To the fort.”

“A fort?”

“A national monument. But no one goes there now, joven.” “¿Por qué?”

“Because it is very, very cold. But I will take you.”

They drove away from the town’s asphalt streets, and into an unpopulated, windblown and foggy pampa-scape, where there were no trees but many bushes, clinging to the soil against the winds that blew in from the South Pole. Joe explained his mission, his travels overland and by ship from the United States, and on all the roads of South America.

“This is the end of your trip!” the driver said. “There is no more road after this.”

The narrow road turned to gravel, and after thirty minutes they reached a sign that read fuerte bulnes and the road became a loop and circled back on itself, and Joe realized this was, in fact, the end, the last stop in the chain of highways connected to Cartagena, on the northern shores of the continent. The bottom of the bottom. It was an old fort built by colonists who no longer lived here, and now a tourist attraction that no one visited in the winter. He saw a fence made of sticks, a palisades and a Chilean flag, its red and white stripes snapping south in the wind, in the direction of uninhabited, inhospitable islands and Antarctica across the ocean. Climbing the slope on which the fort resided, he saw the soapy blue current of the famous straits sought out by European mariners. Calm ocean water, sheltered from bigger, meaner seas. Magellan and his crew navigated through this channel, their Portuguese sails catching the wind, steel helmets rusting in the misty air, the captain and his sailors thinking: Is this the way, have we found it? Asia and spices and riches! Magellan’s eyes upon the way forward, to Japan and then Africa and home to Lisbon. And now my eyes on this same body of water, lonesome waves. From Urbana to here. If Mom and Dad could see me. Now I know what the explorers knew: how big the globe is. My world is roads, oceans, rivers, bays, deserts, jungles, bridges, gas stations, crossroads, signs, swamps, dust and ice. Big, but finite.

There was only one thing a bum could do when he’d reached the end of the world: turn back and bum northward and eastward to the next place.

__________________________________

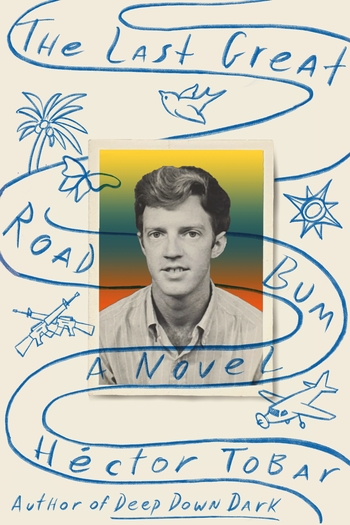

Excerpted from The Last Great Road Bum: a novel by Héctor Tobar. Published by MCD, an imprint of Farrar, Straus & Giroux. Copyright © 2020 by Héctor Tobar. All rights reserved.

Héctor Tobar will be in conversation with Oscar Villalon at City Lights Bookstore on 9/1 at 9 pm ET; find more information here. To watch his event with Roberto Lovato at Chevalier’s on 9/3 at 10 pm ET, find more information here.