The Knife’s Edge Between Dopesickness and Delusional Hope: Keri Blakinger on Her First Week in Jail

“I walked out of my cell into a brave new world I still did not understand.”

Tompkins County Jail, December 2010

My first week in jail was a blur. Not a complete blackout—I didn’t wake up one day and wonder where I was or how I’d gotten there—but I sure as hell couldn’t outline any details of the process.

For the first day or two, I alternately slept and snorted the heroin I’d smuggled in. I wasn’t even subtle about it; it absolutely did not occur to me that bringing drugs into a jail could be another felony, or even that it was possible to catch another felony when you were already locked up. Jail was the most serious consequence I could imagine, and the idea that there could be worse things in store didn’t really compute.

The evening of my arrival, I ripped a little strip off of my legal paperwork and rolled it up into a straw, then snorted the soft brown powder from the top of the metal cell desk, kicking off the first step in a familiar cycle: get high, pass out, rinse, repeat.

At some point—maybe my first morning in jail—the other women woke me up to point out my mugshot flashing by on the news.

“You’re famous,” one said, with a touch of irony and a raise of the eyebrows. Barely able to stand, I leaned my head against the cell bars and squinted at the pocked face glaring down at me from the TV. Had I been more sober, I might have felt ashamed or embarrassed. But if the thought did not occur to me, it also did not seem to occur to my new blockmates. Some seemed thrilled at the excitement of knowing a minor celebrity, a flash of something interesting in the monotony of jail life. Others were just too kind to point out how bad I looked.

They probably understood the seriousness of my situation better than I did.

When I got called out that day—or maybe the next—for my first court trip, I stuffed the remaining dope back up my ass, then mindlessly chucked the rolled-up paper under my bunk where any observant passerby could have seen it. A woman two cells over walked by and warned me not to be so careless, but the guards chose not to notice or to question why I was still so high. They just asked everyone else in the block to keep an eye on me and make sure I was still breathing as I nodded out again and again, knocking my head on the cell bars when I stood and falling asleep in improbable contortionist positions when I sat.

I knew I would have to come down eventually, and each line was only buying time, stalling my return to the jagged metal corners of reality. Eventually, I would get dopesick: There would be sweats and chills. All the things that usually happened when my dealer was dry or I just ran out of money: twitching, restless legs, ants under my skin, diarrhea, catatonic despair. Like the flu on steroids—but this time instead of an empty Collegetown drug den, the setting would be the floor of the county jail.

When you are dopesick you do not make good decisions. You miss exams or skip work. You sell sex on dark streets and shoot up in public places. It’s not just that you are desperate to feel better, but also that everything seems foggy, and distinctions—like right or wrong, risky or safe—feel more fluid, at least until you’re high again and can willfully ignore the difference. This is to say: Dopesick is not a great frame of mind for hard choices, like how to handle a legal case or whether you want to stay sober.

Short of getting more drugs smuggled into the jail—which was not out of the question—there were two alternative possibilities to that coming sickness: one, release. The other, medication.

In the first hours after my arrest, I’d harbored some delusional hope of getting out immediately. I knew I had a decent amount of drugs, but I wasn’t sure if six ounces—enough to fill four or five cigarette packs—was a lot in the eyes of the law. I wasn’t running a Scarface-scale operation, but in New York it really didn’t matter. Anything over four ounces was enough to earn you football numbers, prison slang for the double-digit sentences that belonged on the scoreboard at the end of a game.

The next day, I was cogent but still in a light haze when I was cleared to be in general population. I walked out of my cell into a brave new world I still did not understand.

That’s because the Empire State was once home to the notorious Rockefeller drug laws. Signed by Republican governor Nelson Rockefeller in 1973, those laws were an opening salvo in the War on Drugs and a way for an ambitious politician to look tough on crime. They made the minimum punishment for just having—not even selling—four or more ounces of hard drugs fifteen-to-life, even on a first offense. Other states rushed to follow suit, even though the new laws made the New York prison population increase fivefold and heightened racial disparities, filling the state’s prisons and jails with even more Black and brown bodies.

It wasn’t until 2004 that activists convinced the state to change the law. First, the legislature eased the harshest sentences, and five years later—just one year before my arrest—they mostly dismantled the rest of it.

Under the old law, I could have been looking at at least a decade and a half behind bars—with life on the back end.

But I didn’t know that at the time. There was no one in my life who could explain that, or tell me how lucky I was; all I knew was that the women around me said I probably wasn’t going to get out anytime soon. I was charged with an A-2 felony—a class of crimes that included predatory sex assault, use of biological weapons, and hard drugs over four ounces—and thus automatically not eligible for bail.

And if I wasn’t getting out, that meant there was only one other way to avoid dopesickness without doing anything desperate: Suboxone. The six-sided orange pills nicknamed “subs” were a combination of two drugs—buprenorphine and naloxone—that would ease the pains of detox and make it almost impossible to get high. Basically, dope just wouldn’t work; the rush would be muted, unsatisfying.

Usually, Suboxone is prescribed for long-term use, to help people stay off drugs and lower the risk of a relapse; it’s after a period of sobriety—like jail—that heroin is at its deadliest, when you think you can do as much as you used to and don’t realize that high you seek will now kill you. Sometimes, though, Suboxone is just prescribed in the short-term—only a few days at a time—to ease the symptoms of dopesickness down from a super-flu on steroids to a weeklong, uneasy discomfort.

Most jails don’t stock it at all, but the other women told me that Tompkins County was different. They, apparently, weren’t worried about accusations of “coddling” inmates, at least not for a few short days for detox. One problem: Getting it was no guarantee. Access to medical care was arbitrary, and the nurse, I was told, was known to play favorites. If she decided she didn’t like you, you got Tylenol and a jar of Kool-Aid while you shat yourself and threw up for three days. But if you fell into her favor, you won access to the chalky orange pills and saccharine taste of salvation.

On my third day behind bars, my salvation showed up on the morning meds cart. I breathed out desperation and inhaled relief as the orange tab dissolved on my tongue and a nine-year fog began to recede.

The next day, I was cogent but still in a light haze when I was cleared to be in general population. I walked out of my cell into a brave new world I still did not understand.

The Tompkins County Jail was small, as far as county jails go. While big-city lockups like New York City’s notorious Rikers Island could easily house more than 10,000 people, the single-story brick building outside Ithaca held roughly 100 at full capacity. Up a long, sloping hill north of town, it was just far enough to make visiting a hassle for poor families without cars. The building went up in 1986, and by the time I got there in 2010, it looked like an aging jail sent back home from central casting because the wrinkles were showing.

The cell walls had been painted over again and again, beige tones over blue ink graffiti from generations of unhappy inhabitants. In one block, the cement bricks in the waist-high privacy wall in front of the shower had been kicked so much they’d crumbled down to knee height. But the most visible sign of age felt theatrical, like a dark expressionist distortion of reality: the oversized clanging metal bars on the sliding gates at the front of each cell.

Jail architects did away with that kind of design more than a decade earlier, and the guards always told us it was because the bars on each cell made it too easy for people to kill themselves; bars, poles, anything desperate people could tie a makeshift noose to represented a risk. All the newer jails had isolating, solid doors instead of sliding gates. Those doors were supposed to be safer, but the old-fashioned gates meant we could always talk to each other. The guards could lock us all in, but we would never be entirely alone.

Our cells ran down the outside walls of the building, with long horizontal windows at the top where we could not see out of them. If we stood on our bunks to peer out, the guards would yell at us. We wanted to spy on the visitors in the parking lot or gape at the wild turkeys across the highway; they wanted us to sit the fuck down and shut up. The bunks themselves were metal, two to a cell. We tried to make the place homey by using chalky county-issued toothpaste to stick decorations to cement walls and metal bunks. Most people favored photos of their pets or boyfriends or children; I had no such images, so I pasted up a copy of the Stevie Smith poem “Not Waving But Drowning.” In any case, our attempts at decor were against the rules—though I was never sure what was a real rule and what was an unwritten rule. In The Twilight Zone of jail, it didn’t really matter. They were equally enforceable.

________________________________

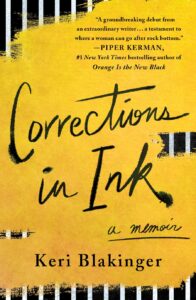

From Corrections in Ink by Keri Blakinger. Copyright © 2022 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.

Keri Blakinger

Keri Blakinger is an investigative reporter based in Texas, covering criminal justice and injustice for The Marshall Project. She previously worked for the Houston Chronicle and her writing has appeared everywhere from the New York Daily News to the BBC and from VICE to The New York Times. She was a member of the Chronicle's Pulitzer-finalist team in 2018 and her 2019 coverage of women's jails for The Washington Post Magazine helped earn a National Magazine Award. Before becoming a reporter, she did prison time for a drug crime in New York. Corrections in Ink is her first book.