The Joy and Privilege of Growing Up in an Indie Bookstore

Erik Hoel on His Formative Years in the Shelves of His Mother’s Bookstore, The Jabberwocky

There are only about 2,000 or so independent bookstores in the United States, and I was lucky enough to grow up in one of them. In 1972, when books sold for around 75 cents, my mother Susan Little was a young hippie living in Newburyport, Massachusetts. She worked at the local bar, slinging beers to fishermen who would come in so rich from their catch they would throw $100 bills onto the fire to laugh as the bills curled in the flames. After a few weeks of partying ashore the fishermen would be flat broke again and head out to sea to repeat the pattern. Located about 30 miles north of Boston, Newburyport was at the time so economically depressed that it almost razed its historical wall-to-wall brick city center to make way for shopping malls and housing developments. Saved at the last minute by a federal grant, the town filled up with artists and craftsmen, a vibrant community, and my mother wanted to be part of the restoration.

She knew nothing about owning a business, or selling books, and she didn’t have any credit. She saved $2,000 from bartending and a local bank loaned her another $2,000. It was utter nonsense for a 23-year-old woman in 1972 to open her own store, so she called it “The Nonsense”—The Jabberwocky was born. When in 1974, after meeting all her payments to the bank, she asked to borrow another $4,000 to move The Jabberwocky to a larger space, she was told that as a young woman in the 70s she’d be “doing other things soon” and was declined.

It was utter nonsense for a 23-year-old woman in 1972 to open her own store, so she called it “The Nonsense”—The Jabberwocky was born.

Undeterred, she eventually moved the store to an old tannery in 1986, expanding from 650 square feet to over 7,000. The fact that it’s a bookstore not situated anywhere near a university, or in a major city, but in a town with a population of less than 20,000, makes this especially impressive for anyone who knows this industry well.

Newburyport has been thoroughly revitalized compared to its “bad old days,” and the store has been part of that. Even during my childhood in the 90s the town was nowhere near as upscale, diverse, and chic as it is now. That preserved historical brick facade is currently the center of a real estate market so hot that the Wall Street Journal writes articles about the multi-million-dollar nature of it.

When COVID-19 came, and the lockdown soon after, Susan contemplated that maybe this was the universe telling to her close up shop. It had been almost 50 years. But through a miracle The Jabberwocky survived — no, not a miracle—the store made it via the kindness of its customers and community, who rallied around it and raised over $60,000 on GoFundMe to keep it open.

The store is likely to be sold soon when my mom retires, but there’s no longer any plans on closing it. “The store doesn’t really belong to me anymore,” she told me recently, “it belongs to the community.” Perhaps one of the last events of the store under her ownership will be a post-covid launch party for my debut novel. While my digital launch party is happening (virtually) at New York City’s Center for Fiction with Andre Dubus III, it’s strange to think about one day going to sign books in a place that was, effectively, my living room.

Despite financial troubles there’s a sense in which my childhood was immensely privileged — a pauper in the material world, I was a sultan in the world of ideas.

Being a single mother and raising two kids meant that my mom has spent most of her life working at the store, so that’s where I spent the majority of my time as well. A beneficiary of neglect, I read what I could reach. Up, up, up the shelves! Greedy thin arms outstretched. Running a bookstore is not exactly lucrative, and most profits went back into the store. For years, the plumbing at home was broken, so in the morning I bathed for school via water heated on the stove and poured into the bathtub for a few inches of warm water. But despite financial troubles there’s a sense in which my childhood was immensely privileged — a pauper in the material world, I was a sultan in the world of ideas.

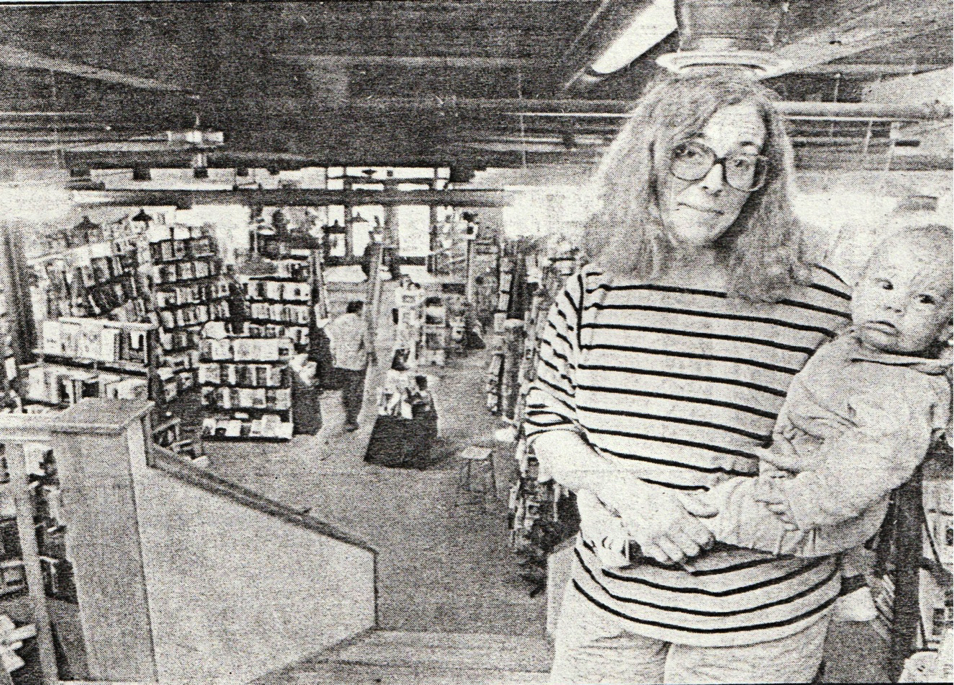

Susan Little holding the six-month-old future author in her store The Jabberwocky Bookshop (1988).

Susan Little holding the six-month-old future author in her store The Jabberwocky Bookshop (1988).

My childhood friends and I would sleep there sometimes, while my mother went on all-night manic work sprees to keep the store afloat. A bookstore at night is a whole other world to a child, full of secrets, sometimes frightening, creaking and large and filled with corridors of shelves. A child moving through these is a sprite entering another world, a sybaritic sensorium, wherein you can plop down at any point, spread out a book, and enter some other point-of-view.

In one of Umberto Eco’s lesser-known works, The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana, an amnesiac narrator returns to his childhood home after a stroke to try to recover his memories. The book documents his obsessive process of recreating his personality, which he does by assembling and reviewing the pop culture artifacts of his youth: the striking old posters, Italian cartoons and translations, dusty records, and rereading the old books, pulp adventures and serious literature both, viewing it all again with childlike eyes such that everything, every dame in trouble, every hero carrying her in his arms, every shadow of a villain with a gun, takes on again that density of meaning that only the youngest have access to.

“Had I tried to remake myself completely among those pages, I would have become Funes the Memorious, I would have relived moment by moment all the years of my childhood, every leaf I heard rustling in the night, every whiff of coffee in the morning.”

If it were indeed possible to reenact the mysterious alchemy that makes a person become who they are, perhaps through clever hermeneutics, through semiotic wizardry and exegesis, there’d be no doubt one could recreate my entire persona from the contents of The Jabberwocky. Just start low and go up, up, up the shelves!

If it were possible to reenact the mysterious alchemy that makes a person become who they are, one could recreate my entire persona from the contents of The Jabberwocky. Just start low and go up, up, up the shelves!

As a teenager working there, I was more interested in reading books than selling them, making me a poor employee. During work hours I would get lost in the stock room, or, having forgotten what I was doing, become a statue reading while carrying stacks of books I was supposed to be shelving.

With the pigheaded romanticism and snobbery of a 17-year-old, I decided early on I didn’t want to be the kind of writer whose career consisted solely of majoring in creative writing, then getting an MFA immediately afterward, and then writing that first novel — for what would I have to write about? Like only a teenager could, I thought it was still possible to romantically sign aboard an outbound vessel to gather material for my fiction like Melville in Typee, end up in the army like Mailer, or immersed in the counterculture like Didion. Yet I doubted my sailing ability, didn’t like the idea of shooting anyone, and if there was a counterculture it wasn’t anywhere near Newburyport. It was then that I discovered the science section of the store.

I gobbled up the nonfiction authors: Hawking, Dawkins, Sobel, Hofstadter. Mythic figures, forms paralyzed in wheelchairs but winged and unlimited in their minds, danced in dreams of meaning. Oppenheimer stood holding the Bhagavad-Gita with low-cast eyes, the blast illuminating defiant cheekbones. I began to imagine a novel set in the world of science, abstractly, with little idea of what it would actually be about. I had read science fiction, of course, but where was the great novel of science, of the process itself? Its struggles and methodologies, its characters, its humanness, its inhumanness.

I’ll write it! I thought. All I would have to do is go to college, become a scientist myself in an interesting field that contained all the necessary drama to portray science appropriately, and use that material for a novel. It was an insane idea. But five years later I was accepted to graduate school for neuroscience, and I worked with some of the world’s leading researchers trying to develop a formal scientific theory of consciousness.

What is an adult but the continuation of some formative process, fixed long ago, now running itself out?

Consciousness remains a scientific mystery — the fact is we have no good understanding of why certain neural events in the brain are related to experiences. How the extrinsic relationships of physics and the brain generates the intrinsic experiences of consciousness is still unknown. Yet despite its scientific mystery, consciousness is the natural environment of a writer. Novels are a special medium, the only one capable of taking the intrinsic perspective on the universe. TV shows get high production values and incredible special effects, video games get improved graphics and addictive gameplay, but the novel is the only media that can directly represent people’s consciousness.

So it was there at the crossroads between the subjective and the objective that I set my novel, The Revelations, which follows the murder of a consciousness researcher.

Susan Little next to her son the author, holding his debut novel, in her store The Jabberwocky Bookshop (2021).

Susan Little next to her son the author, holding his debut novel, in her store The Jabberwocky Bookshop (2021).

Recalling the provenance of this decade-long effort makes it seem somewhat provincial to me now. The Revelations is the result of a mad quest by a boy. Science is massive, many others have written about it, far too many to begin to name here, and the idea of greatness in literature is both suspicious and embarrassing. Still. What is an adult but the continuation of some formative process, fixed long ago, now running itself out? The best parts of us are perhaps the teenagers who set us down this path, and we adults, cynical, overly critical, thankfully cannot help but carry out designs more fanciful and innocent than any we would originate now.

What more can a bookstore kid turned author say about independent bookstores? That they are the best place to grow up? Obviously. What more can I say about my bookstore? I can say that there is a particular view when you walk in the store through double doors, a perspective from a raised annex with stairs that descend down to the shelves, a view that looks out over the panoply of covers and the occasional browsing figure, and that there is a redolent smell, and music in the air. The experience is so powerful, coiled so tightly around my cortex, that I expect it to be the last thing I see. The doors will open to a small jingle, and I’ll walk through them, see those pretty books lined up and smell that sweet cloistered air, and in a final metamorphosis I’ll also become only words.

___________________________________________

Erik Hoel’s The Revelations is available now via The Overlook Press.

Erik Hoel

Erik Hoel received his PhD in neuroscience from the University of Madison-Wisconsin. He is a research assistant professor at Tufts University and was previously a postdoctoral researcher at Columbia University in the NeuroTechnology Lab, and a visiting scholar at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. Hoel is a 2018 Forbes “30 under 30” for his neuroscientific research on consciousness and a Center for Fiction Emerging Writer Fellow. The Revelations is his debut novel. He lives in Massachusetts.