The Journey of a Madwoman: Between Facts, Memory, and a Fractured Self

Suzanne Scanlon on Remembering and Returning to a Disappearing Past

I started with a walk. The walk would lead me into the past. It took me to a hospital. A hospital that was no longer a hospital. That was the idea. I would describe the hospital, my home. If I could walk, I could remember. It wasn’t nostalgia. My memory is disordered. The building had an order. The book could hold the memory of my disordered mind. Anne Sexton: Not that it was beautiful, / but that, in the end, there was / a certain sense of order there; / something worth learning / in that narrow diary of my mind, / in the commonplaces of the asylum.

I would describe the brick, the lasting grandeur and the dense order of its design would become my book and my book would be a place to live. Every good story is two stories said Grace Paley and so this was true too with Committed—the book a story of the past, a time I spent in a place, but also the story of the person telling the story: this woman who can’t stop herself from walking back to the brick building. She will attempt to walk herself into the past through geography, photography, medical records, and notebooks. I assemble my materials, I do my field work. I know the walk is a pretense; everything I write is an elegy. I have no choice.

I know I pretend to walk into a past self when in fact what I know most about those years is that I was a no-self and that no-self of me was what I thought my problem was. I thought I was supposed to have a self. So what I look for now is something more like the self who was seeking a self who because the self writing this story about a coherent self she no longer believes in. Self as a fixed thing. David Foster Wallace on what we can learn from Kafka: The horrific struggle to establish a human self results in a self whose humanity is inseparable from that horrific struggle.

I know I pretend to walk into a past self when in fact what I know most about those years is that I was a no-self.

I finish my walk. I’ve found my way in. The walk will be published. The fact checker emails me. He needs to know more about this walk, about my imagined geography. It wasn’t imagined, I say. I was there. Had I taken notes? Some of what I said I saw could be verified and some could not. The benches. I remember the benches. I remember myself, leaving the hospital, going in and out, if the weather was nice we would stop, sit on the benches. Nothing warm or comforting about the benches, marked with roman numerals, hard and cold reminders of the original asylum architecture, meant for containment. But now months later, before the essay goes to print, the fact checker is telling me that I am wrong. I was wrong about the benches. I was wrong about the dates, too.

According to the hospital website, he explains, the New York State Psychiatric Institute was founded in 1895 and affiliated with the Presbyterian Hospital in 1925. Your roman numerals are 1927. Where did you find 1927? I wasn’t sure. Maybe I’m just stupid about roman numerals. Well, he said, I’ve been looking for the benches, and I can’t find them in any pictures or on Street View. That’s not to say they aren’t there, he added, kindly I thought, but if I can’t find them, I can’t check the numbers. I see. It may be that the official opening date is not the same as the affiliation with the hospital. Right. Well, I think you should revisit the reference. I said that I would.

That night I search the internet for benches, pillars, and roman numerals. The problem is that the building remains but is no longer a psychiatric hospital. The name engraved in the brick, the original incarnation as asylum, isn’t legible in the new official Columbia University photography. This is not accidental. This rebranding. I notice that the promotional materials for what is now the School of Public Health go to great lengths to erase the architectural detail that was key to the asylum structure—both the archway with the building’s name NEW YORK STATE PSYCHIATRIC INSTITUTE AND HOSPITAL—and the detail below it, which features the bars, prominent in the original design. The photos on the website are framed to erase these details.

The new psychiatric building was designed by a celebrated architect, and the project features prominently in search results. So I try searching for my former return address. I find a postcard Edie Sedgwick wrote to Andy Warhol with that same return address. Like me, she wrote letters from the hospital when she’d lived there. I find an uncategorized and undated assortment of official and unofficial images of the building’s exterior. Here’s one from Wikipedia and another from a defunct social media site. The pillars appear and disappear over time. In one photo, the pillars become planters. Finally, I find a photo that shows the benches, not quite as I remembered, both to the left leaving the building, but still I didn’t make them up; they were there. Benches! I email the fact checker.

The next day—because I’ve only just started, because this walk will lead to many walks—I find a photograph of the hospital from 1887, showing the entrance as I recall it, the design then-standard asylum architecture, in the New York Public Library’s digital collection, a catalog of “New York Mental institutions.” There is also the Bloomingdale Asylum, which was a home for the mentally ill at Broadway and 116th street, before Columbia University and Barnard College occupied the property. That former asylum building is now a building of Columbia’s Teachers College. The Bloomingdale Asylum was known for taking patients against their will—i.e. men could and often did sign their wives into the hospital—as well as its horrible treatment of patients. Or the New York Asylum of Lying-In Women, in Greenwich Village, a property that later became part of NYU’s hospital. All these buildings still standing.

The most exciting image I find is not linked to the university or the hospital at all, an image of the back of the building, which used to be seen from Riverside Drive. The image is used to accompany a news story featured on a cyber security company. News of a data breach at the NYSPI. Here I see I was right—the windows were barred—and it was as awful and carceral as it looks in this photograph. The hospital and university do not include this image on their website or even in the archives of the building.

The journey to the past is always the journey of a madman.

Some months later I decided I would take a tour, I would return, I would try to go in. It was uncanny to enter the rooms, the stairway, the floors. I found the traces, the skeleton design, and I could see what remained of the past. The man leading me on the tour asked me why I wanted to be there. What I was looking for. I’m looking for what used to be here, I said. There was one floor, the fifth floor, that’s what I wanted to see. The elevator I remembered where patients and staff came and went, the elevator was no longer operable, not up to code, but when I saw it there, I saw the operator, who always wore a white shirt, sat on a bench. He took me down each hall and I noted and I felt this was my bedroom, this was Amy’s bedroom, this was where we lined up for meds, this was where we sat and smoked.

And then the center of the hallway, what I try to describe in the book as an E, sketching it out, the large room that our leaders called the Community Room, the room where we gathered each Wednesday, where I was presented before I left, where we watched TV, the OJ car chase in the white SUV and the OJ trial. Now it is something else, it is large and the windows have opened. The view of the Hudson is larger, grander, something hopeful, promising. What’s possible with an old building. The afternoon light from the west. Or was it always this way. Are the windows larger or just the same old windows?

What are you looking for? He asked again. He is kind, not suspicious, merely curious. It is unusual. I am looking for the past, I say. He understands. I wasn’t here back then, he laughs, but I’m happy to show you. Before we leave he takes me to an office on the first floor. He introduces me to a building manager who has been there a long time. The manager doesn’t know anything about the benches. On the wall I see a photograph of the basketball court on the rooftop. I’d forgotten but now I remember. I don’t think we ever went out there but it is familiar, and familiar too, the cage around it. This was where the patients played, he said. Many patients, he said. Many people say the place is haunted, he says with a smile.

Here I could say something obvious about the past or my past or the ghosts but now I was done, I wanted to leave, this would not get me to the book, I knew that by now. It was funny to think that I could be an archaeologist or an ethnographer, and besides I wasn’t feeling well. I excused myself, said goodbye and thank you for your time. As it turned out some days later I fell ill and tested positive for Covid. I couldn’t know but I became convinced it was there back in my past, among those ghosts that I’d been infected with, the plague as punishment for my return, for an impossible journey.

Now I remember Sexton’s epigraph—for John, Who Begs Me Not to Enquire Further—and how she was quoting Schopenhauer’s letter to Goethe: Most of us carry in our heart the Jocasta who begs Oedipus for god’s sake not to inquire—and I imagine John a lover or husband concerned not with propriety but with sanity, concerned for the writer who knows that madness might lie at the end of a journey and that the journey to the past is always the journey of a madman.

__________________________________

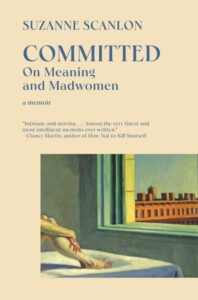

Committed: On Meaning and Madwomen by Suzanne Scanlon is available from Vintage, an imprint of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Suzanne Scanlon

Suzanne Scanlon is the author of the novels Promising Young Women and Her 37th Year, An Index. Her writing has appeared in Granta, BOMB Magazine, The Iowa Review, and The Los Angeles Review of Books, among other places.