Jen Silverman on Generational Divides in American Politics

In Conversation with V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

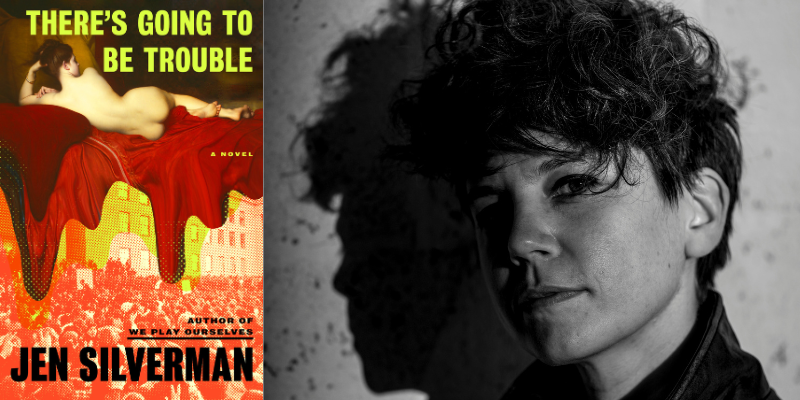

As the presidential election heats up and President Joe Biden struggles to keep young voters’ support, novelist Jen Silverman joins co-host V.V. Ganeshananthan to discuss generational divides in U.S. politics. Silverman, whose new book, There’s Going to Be Trouble, follows the political and sexual awakenings of a father and daughter in different eras, talks about how young people’s involvement in politics now compares to previous generations’ engagement. They address the question of whether today’s 20-something voters are more likely to protest than vote, consider how social media and technology relate to in-person conversations and activism, and reflect on the need to name and engage with the failures of earlier generations. Silverman also explains why they chose to write about anti-Vietnam War protests at Harvard in 1968 and the gilet jaunes (Yellow Vest) protests in Paris fifty years later, and reads an excerpt from There’s Going to Be Trouble.

Check out video excerpts from our interviews at Lit Hub’s Virtual Book Channel, Fiction/Non/Fiction’s YouTube Channel, and our website. This episode of the podcast was produced by Anne Kniggendorf and Alijah Smith.

*

From the episode:

V.V. Ganeshananthan: Keen, as an older man, does seem very different from his younger self, and I wonder if you think that we engage in protests differently across generations? Or do we just get older and become more risk-averse?

Jen Silverman: You know, I know a lot of older activists and a lot of older queer activists particularly, so I will resist my own desire to make a blanket statement about protest and risk for the young. But I will say from what I was interested in interrogating with Keen, specifically, was a person who believes that risk is worth taking, because he believes that in the end, he will have had an impact on the world. And not only does he find that the world keeps turning, and all the things that he thought were terrible and unjust continue to exist, but also—without spoiling the end—he gets pulled into a tragedy of sorts that is unplanned, he makes a series of decisions that have unforeseen consequences, and I think he comes out of that realizing how fallible he is, and therefore how fallible other humans are.

And by the end of the book, I mean, one of the things that he is trying to impart to Minnow is that how can we possibly change society when the building blocks of society are still humans and, regardless of how hard we try, humans are selfish and afraid and weak and incapable of acting without self interest. I mean, this is Keen’s perspective, right? But I think that he was radicalized by falling in love with Olya and by falling in love with the potential of having power. He is sort of cynicized or pulverized by the outcome that he encounters such that he is no longer able to hope for a different future. And being raised by someone who is not able to hope for a different future, I think, is the thing that ultimately Minnow chooses to be radicalized against.

But this conversation between what happens when someone from one generation has lost the ability to hope, and someone from another generation is sort of furiously seeking a thing that will give them hope – and I say furiously because there’s some rage against, “Why didn’t you raise me to have any hope,” right? – like, that’s the tension that really fascinates me, and I have encountered that tension in my own life. I’ve encountered it inside my family. I think it’s hard, the more you—and I feel this myself—the longer you live, and the more that you see failures stack up, failures of policy, failures of protest, cultural failures, you know, it’s hard to maintain an engine of optimism.

VVG: Dark, but also, I mean, Keen’s a very persuasive character. I was interested in how much sympathy I maintained for him even as he began to behave in less and less sympathetic ways. Like when Minnow is facing that public backlash for helping her student, Keen, who has guarded his privacy very zealously for some years, one of the things he’s angry about is that she has exposed him, that his walls are not high enough. And he had thought that they were, and he’s extremely angry at her. And she kind of has a moment where she’s wondering, why is he not expressing more concern for her, really? And it’s this moment of rupture. It’s really powerful.

And one of the other tragedies of the story, the way that people are really repeating each other. And how do we? I mean, I think one of the big questions for me as I was reading this was: “What are our mechanisms for change? How do we address, how do we identify them? And how do we really participate in them? And what does it mean, to do that, when your hope is not maybe even there?”

We had Emily Raboteau, who writes about climate change, on a couple of episodes ago, and she was Tweeting recently about people always asking her about hope. And her response was that she was interested in the animating force of anger. Which I’ve found—I was like, yes, that’s where I go, too, but then that’s a different kind of exhausting.

JS: Yes, yes. I’m realizing, as you’re saying that, that I think something that fascinated me about Minnow and Keen both is that it was the animating force of love, as you know, that it wasn’t necessarily anger, it wasn’t necessarily hope, but that each of them is radicalized by falling in love. And that when you fall in love, you see yourself differently, you see the person across from you differently, like there’s a way in which you start to read a whole new possibility into your environment, even if, you know, perhaps it would be short lived, I don’t know. But that’s the sort of the sexual awakening and political awakening for each of them. The one triggers the other, right?

VVG: Which is, in some ways, maybe almost a trope of literature about movements. And yet also, like, I think it’s a trope, because it’s often accurate. I think about what I wrote my journalism school thesis about—literature of the Weather Underground—and you would often see this play out in some of that literature so, I don’t know, it was interesting to see Minnow make really distinctive choices and to feel that she had a lot of agency as a character. Because that’s often what I want—I want women characters or femme characters to have some power, but she is also very much at the mercy of the things around her and very much swayed by this emotion for the very charismatic Charles. Charles comes on the page, and I was like, “Oh, God, he’s so hot.” I was like, checking my watch. I was like, that’s gonna happen. When is that going to happen?

JS: And this is the thing: I think the engine of anger has some staying power. The engine of hope definitely has staying power. But the engine of falling in love is complicated. Because it can propel you, I think in ways that are, all of a sudden… I mean, with Minnow at least, all of a sudden there’s a moment of “Wait, where did I get myself into the middle of?”

VVG: And I think maybe not for Keen as much, but Olya also, she appears in a very striking way that I won’t spoil, but I could imagine the film. And she appears on the page, and I was like, “She’s also hot.” She’s so charismatic. And then I was like, and this is why sometimes you’re drawn to listen to someone, because maybe being politicized is like falling in love, that you become entranced with a subject such that you’re willing to study it and look at its different angles and argue its pros and cons.

I was glad that there was a woman’s point of view and a man’s point of view. I think often the trope actually is like—maybe I’m quoting Dana Spiotta—but when you write about activism, and there’s like a young woman who has a political awakening, and is it just because of some guy, and like, is that kind of frustrating? But I love how this book complicates that, in so many ways, because of Charles’s class status and his family background, and his own uncertainty about his position and authenticity as an activist, the age gap, Minnow’s very particular history, it becomes such a specific and believable and alive relationship. I just really appreciate it.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Madelyn Valento. Photograph of Jen Silverman by Zack Canepari.

*

There’s Going to Be Trouble • We Play Ourselves • The Island Dwellers • Bath • The Moors

Others:

Family Ties (television sitcom) • Changing Partisan Coalitions in a Politically Divided Nation | Pew Research Center • “Who Are France’s Yellow Vest Protesters, And What Do They Want?” by Jake Cigainero | NPR, December 3, 2018. • “The Generational Rift that Explains Democrats’ Angst over Israel” by Steven Shepard and Kelly Garrity | Politico, October 12, 2023 • “Less than Half of Young Americans Plan to Vote in 2024, Harvard Poll Finds” by Joseph Konig | Spectrum News • “Young Voters are Unenthusiastic about Biden, but He Will Need Them in 2024” by Dan Balz | The Washington Post • “Climate Activists Target Jets, Yachts and Golf in a String of Global Protests Against Luxury” by David Brunat | AP News • “The Weapons French police use During Protests” by Jean-Philippe Lefief and Marie Pouzadoux | Le Monde, April 6, 2023 • Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 7, Episode 24: “Emily Raboteau on Mothering and Climate Change” • The Diary of Virginia Woolf, Volume 5 by Virginia Woolf