When he was still very young, Chico thought that all other families were just like his. All children had two mothers, and their mothers were as sweet as his (but his mothers were the sweetest of all). He believed that if he ate up the ants that crawled around his fish mush he would gain superhero eyes, because “ants are good for the eyes.” He thought that when he got a bump on his head a little chick would emerge from behind the lump. He thought the kettle whistled because it was alive, and that if he ate too many lollipops his tongue would turn red forever. He believed that Captain America lived in a faraway land behind the nearby mountain.

As he grew up a bit, he began to realize things weren’t quite like that. Families like his did not exist. He had to have a father, like the one in his schoolbooks, with a dark suit and slicked-back hair. People only had one mother, and siblings could come in great numbers, but they didn’t come and go like his. He started to suspect that ants were only good for the eyes when one or two fell into the porridge and his mother Guida was too tired to pull them out. The bumps did nothing but hurt, though he still secretly hoped that one day he’d see a chick hatch from them. Why the kettle whistled he still didn’t know, but it certainly wasn’t alive. His tongue would indeed turn bright red forever if he ate too many lollipops, and this, his two mothers swore, was the absolute truth. As for Captain America, he didn’t live behind the mountain. He lived in a place that could be reached only by plane. The man who lived behind the mountain was Saci-Pererê, the one-legged devil in the red cap who always went missing with some household item or another.

By the time he reached the age of ten, Chico was sure he knew everything. His two mothers were tarts, because that was the word he’d heard from one of his classmates, who Chico challenged to a fight even though he wasn’t sure what a tart was. He arrived home covered in blood and got an earful from Guida, who later regretted her words and made him some porridge. Guida was so worried about her son’s swollen face that she herself removed the ants from his bowl. “This thing about ants, it’s a lie, isn’t it, Mama?” She changed the subject. Chico already knew that no chick would come from the bump that formed on his forehead after the fight, and that the kettle whistled because of the steam, as it did that night. Aside from his wounds he also had a chest full of mucus, so Filomena boiled some water with eucalyptus extract. Then she gave him a lollipop and didn’t even bother to say that his tongue would turn bright red forever. How good were those nights when he was feeling sick; his mama Guida would let him sleep in her bed so that he wouldn’t be afraid of all those monsters who lived behind the mountain, since he already knew that Captain America lived far away and would never arrive in time to save everyone.

In spite of the lollipops, affection and bowls of porridge, Chico grew up a bit resentful that his life was so good and yet it wasn’t life as it was supposed to be. That he had two mothers who were as sweet as they were scorned. Why had a woman crossed the street and spit as she muttered harlot when she saw Filomena walking by? Why had they called his mama Guida “a lady of the night,” if he had never seen his mama outside the house after 6pm? Why could Filomena only arrive at church after Mass had begun and leave shortly before it ended? Everything was wrong, he thought, and the more he learned about the world the angrier he became.

When he was eleven, Chico turned from a bit resentful to extremely resentful. Filomena, his mama Filomena, began to feel a pain in her breast, caused by an enormous lump. One afternoon she came back from the hospital without a smile on her face, and cancer became a word even more unwelcome than tart, harlot, and lady of the night. Seeing the despondency in Chico’s eyes, Filomena began to smile again. “Don’t you worry, it’s nothing!” She tried pulling the boy on to her lap but gave a yelp as soon as their bodies touched. The pain in her breast was greater than her ability to disguise it.

Guida and Filomena sent away half of the children who had been coming to the house. Filomena spent days moaning in the bedroom while Guida grew new arms and legs to be able to care for both the children and her friend. Chico asked to help, but was ignored by his mother. “Your job is to study and get good grades.” The boy sunk his head into his books and lost himself in the stories. Whenever he looked up he decided everything around him was awful, so he disappeared back inside whichever book he happened to be holding at that time.

Little by little: that’s how Filomena passed away. The radiation served only to leave burns on her arms, the breast surgery served only to make her even weaker. The cancer spread through her organs like mercury through a thermometer; not a single doctor managed to wrench it from her. Filomena and her cancer inhabited the same body, but the cancer only gained space, whereas Filomena lost it. She knew that she was departing, it was only a matter of time. The problem was that time was passing slowly.

***

“Oh for criminy, I’m still here!” Filomena would say when she woke from a disturbed sleep.

The cancer had spread to her head, her legs, and between her ribs. The doctors could do little but save her some time in the waiting line and provide words of encouragement in which they did not believe.

Death would not come. The woman was not so much a woman anymore, rather a pile of wounds sprawled across the bed, but death refused to come. During the day she did not speak, at night she only moaned, and the death that would provide release was nowhere to be found. When Chico was at school, she’d repeat, “I want to die, I want to die!” God heard her words and would respond, “That’s fine, but not today.” Filomena would ask, “If not today, when, my God?” God would respond, “When the time is right.”

The right time was a time that never arrived. Whoever saw Filomena on her way to the hospital turned the other way so as not to see her; those who lived nearby covered their ears so as not to hear her. Mothers began to pull their children from her care, and in the end the only people remaining in the house were Guida, Chico with his head stuck in his books, and thirty percent of Filomena.

The savings put away in the flour jar would be enough to sustain them for a few months of eating chickpea soup, but Guida had more important matters to worry about.

“Give me the injection, give me the injection,” Filomena implored between moans.

The daily dose of morphine given to them at the hospital couldn’t keep up with so much cancer. Guida counted the money in the jar and went to the pharmacy.

“Good morning, Senhor Pedro. Could you get me a few vials of morphine?”

“Morphine? That I can’t do, Dona Guida. Only with a doctor’s authorization.”

“I’ll pay well, Senhor Pedro.”

She tried to convince him with a report on the previous night at home.

“It’s for Filomena. She got up in the middle of the night and tried to run away from home, said she wasn’t going to bring us so much sadness anymore. She passed out in the hallway and we had to carry her back to bed. She woke up delirious, saying that they’d shut the gate to heaven, and that she could see her eight children on the other side. That no matter how much she shouted and shook the rails, no one came to open it.”

“It’s an addictive drug, you know, Senhora . . .”

“How much, Senhor Pedro? I’ll pay anything.”

The extra dose cost half of their savings. The second cost the other half. The third cost the necklace with the medal of Our Lady that Guida never removed from around her neck. The fourth dose cost Guida sprawled across the rug in the back of the pharmacy, with Senhor Pedro panting above her. The fifth dose cost the same thing, and the sixth dose wasn’t necessary. Filomena left the world in the midst of morphine dreams, the way Guida had wanted it.

Filomena arrived in heaven, still high from the morphine, and finally found the gate was open. With each step she took she felt a bit better. After a few meters, she was as strong as she had been as a fifteen-year-old girl.

“So beautiful,” said an angel standing nearby.

“Me, beautiful?” Filomena asked, and the angel responded, “Yes, you. Beautiful,” and handed her a mirror. Filomena saw her perfect skin and white teeth. She was so happy that she gave a kiss to the first person she saw in front of her.

“What kind of manners are those, Filomena?”

“Good manners, Senhor!” she said, and laughed out loud.

“All right, Filomena,” said Saint Peter. “Welcome. Your eight little angels are over there waiting for you.”

Saint Peter knew that hers were good manners there in heaven. He had also laughed out loud when he’d arrived and seen his own face as good as new. You need to have seen what his teeth were like on Earth. Or his syphilis scars.

__________________________________

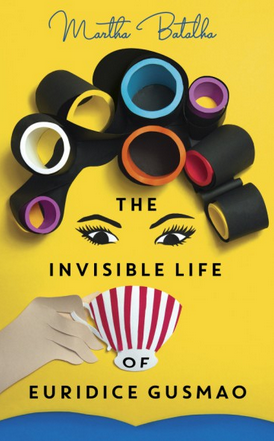

From THE INVISIBLE LIFE OF EURIDICE GUSMAO. Used with permission of Oneworld Publications. Copyright © 2017 by Martha Batalha.