Across the lake

Is that so? we say. Ingram and his Invisible daughter Miss Ingram live close by, Martha tells us, in a grand, impractical mansion of the type the wealthy favor—except Invisible, of course—made from dressed stone the color of spring cream, with a slate roof and glass in every window.

They receive numerous Invisible guests, Martha tells us, who must travel here from other Invisible mansions, in other parts of the country.

That would follow, we say.

They attend fairs and sales about the district. They are regulars at our Wednesday markets.

To sell or to buy?

They are Invisible!

To accomplish trade both parties must be visible, a fact we have not previously had cause to contemplate.

Mr. Ingram’s mansion, Martha tells us, stands on the other side of the lake, at the foot of the mountain. We have inspected the spot she indicates and confirmed it is in no way remarkable. Cold eels of water slide among rushes and sedges and tumps of starry moss. Cat-gorse and furze cling to rafts of drier ground. Spearwort and flag dip their toes and shiver.

Not that we need to search for evidence. If there were a mansion across the lake, our dogs would be howling every time an Ingram passed by. Our daughters would be scouring their pots, our sons sweating in their stables and gardens.

Some accuse Martha of fraud, although what she has to gain by it we cannot determine.

Others say her wits are failing. We’ve known her to put her clothes on back to front and summon her cow with the call meant for hogs. She will stop for minutes on end to watch rooks or lapwings tumble about the sky, as if they bore porridge and dates and the answers to life’s mysteries in their beaks.

But most are happy, eager even, to take her at her word. We want to believe that the Invisible have, for whatever purpose, established their Invisible home next to us. It pleases us to imagine them prodding the fat rumps of our livestock, testing our grain with their clean Invisible fingernails.

Tell us more, we say, and Martha dimples like a girl.

There are many of them, she says. Sometimes the Invisible outnumber other visitors.

But why do they come to market?

For amusement, I suppose. Entertainment.

We look each other up and down, wondering which of us is most entertaining.

The Ingrams have called at Martha’s cottage, of an evening, to pay their respects.

Miss Ingram has such pale hands, Martha says. As if she keeps them folded away in a linen chest.

What language do they speak?

It is English, I presume. I seem to understand some of it. But their speech is strange. Until you are very close, it’s like a noise of leaves or water.

We cannot think why, of all of us, they would choose Martha. She is not the most educated or wise. Not even the most gullible.

Invite us along next time they visit, says Jacob. That should sort the wheat from the goats.

They wouldn’t allow it, Martha says.

What are you afraid of? Jacob says. Let’s settle this once and for all.

Come on, Martha, we say. Let’s settle this. Unless you have reason to be afraid.

I would love to see Miss Ingram’s dress, says Eliza. And her jewellery. I would love to see how she does her hair.

Oh yes, we say. We’d love to see her dress and her hair and her jewellery.

It’s out of the question, Martha keeps saying. They would never agree.

But if there is one thing we know, it is persistence.

Freckled peas

The Vestry can find no regulations that apply. In the past, Martha might have been suspected of contracting with demons, but the Parliament in London has repealed the law against witchcraft. We don’t know if this is because we’ve progressed beyond such superstition or because all the witches have been drowned.

Martha has never been known as a fool or a liar. Once she claimed to have seen a yellow cat the size of a two-tooth hogget at her door, but perhaps she did, and if not, anyone could make that mistake. Jacob complained that she sold him a calf that was already sick and it expired within a day, but they resolved that dispute between them. Mostly she has lived the way we all do, evenly, tidily, respecting time and season. She plants oats and beans and freckled peas on her late father’s holding, keeps bees and chickens, drives her cow to the grazings. She has no husband or children bringing home a wage from the quarry, but then she has no one for whom she must buy tea and sugar. She is a hard worker, if a slow one. When she was a baby her mother, Rebecca, stumbling, as we understand, let her fall in the hearth. In the moments it took the parents to react, flames bit through the swaddling, gnawed the tender infant limbs. We found Rebecca later in the church porch, hanged dead. Martha was left with a limp and, in her breath, a hiss as of hot ashes settling. But she is not one to make excuses. She salts her own bacon, gathers her own turf and bark. She has a reputation as a pickler and preserver, putting up the greater part of her harvest and whatever she collects from woods and wastes. She’s able to sell her surplus to lazier households. She is careful with her animals, keeping them clean and dry. In hard winters, she stints herself to feed them.

Plump and handsome

Martha is adamant that the Invisible are not the Tylwyth Teg, who are known to be short and ill-favored.

The Ingrams are as tall as we are, she points out. Taller. They’re plump and handsome.

Also the Tylwyth Teg are spiteful. They bear grudges for generations. They hide robins’ eggs in shoes, crumble owl pellets into the flour.

The Invisible, Martha says, are smiling always, and if they are not smiling they are laughing. They are generous. Once I saw Miss Ingram pick up a fallen kit and place it back with its fellows.

But on further questioning, she admits such acts of charity are rare. Mostly the Invisible keep apart, chattering among themselves.

How do they dress?

It is the fashion of the city, I suppose, all bright colors and embroidery. And everything always new. Not darned or frayed or even muddy. As if every day is Easter Day.

Do any of them resemble your father? John Protheroe the smith wants to know. Or Price Price or Mother Jenkins?

But we hush him. We don’t want to think that the contents of our graveyard have got themselves up in their best clothes to trot about among us, formulating opinions.

Martha shakes her head. They’re not like anyone I’ve seen before. In looks or behaviour. I believe they’re different from us altogether.

Only child

Martha’s limp identifies her from some distance. It is of the lurching, stiff-legged variety, like a boat hit side-on by a swell. She uses a stick, for walking only, never hitting. When a beast jibs or straggles, she chides, like a doting granny, in a voice you could mistake for praise. She combs the burs from her cow’s tail. Sometimes, milking, she seems to fall asleep with her head on Pluen’s flank.

The only child of only children, since Enoch her father died, Martha has no family at all. She can breakfast at midnight if she pleases, not even trouble to prepare dinner. She has grown thinner these last years. If there were a tempest, such as our forebears talked of, strong enough to strip the thatch from our roofs and topple animals in their stalls, it might blow Martha away altogether, leaving only her shawl hooked in a blackthorn.

Enoch wanted Martha to marry Abel Pritchard. There was a conversation and a handshake and for months Pritchard would call to smoke a pipe or play chess with Enoch. On Sundays, Pritchard would walk her to church, and a comical pairing they made, Martha bobbing in the lee of his ox plod. But in the end he found a girl younger and quicker, with a dowry worth the promise. The bitterness between Enoch and Pritchard lasted until the older man’s death. We do not know what Martha thought.

The Reverends

The Reverend Doctor Clough-Vaughan-Bowen comes all the way from the next county to see Martha. He lodges with the Reverend Rice-Mansel-Evans and early next morning the two men pick their way through a sparkling drizzle to the door of her cottage. Doctor Clough-Vaughan-Bowen is a learned man, of good family. He has written scholarly works, we understand, on subjects of interest to the clergy—adult baptism or the wearing of the chasuble. Rumour says he had a wife who died giving birth to their dying child. Rumour shrugs. When our neighbours and families suffer such losses we take gifts of hyssop or honey to their door, weep with them beside the new graves. But it is hard to believe that men such as Doctor Clough-Vaughan-Bowen have feelings as sharp or deep as our own. Mwynig and Brithen, we remember, bellow through the night that their calves are taken, but next day turn their inquiries instead to turnips.

The Reverend Doctor has not come to reprimand Martha, nor to interrogate her. He talks, in his educated, university English, of which she comprehends a third at most, of many invisible things. Hopes and dreams and memories. The brains of horses. The souls of the dead. The imagination. The future. The swallows sleeping snugly at the bottom of the lake.

He talks of the visible, and the traces it leaves. The fountain that sprang up where the saint pressed his thumb into the earth. The rock pierced by the giant’s spear. The stony pawprint left by Arthur’s hound hunting Twrch Trwyth across the mountain tops.

You see what I’m saying? he says to Martha.

Martha smiles and nods at moments where it seems appropriate.

The drizzle gives way to stumps of rainbow parting a watery sky. The reverends pick their way back and Doctor Clough-Vaughan-Bowen takes his leave, apparently satisfied.

French sauce

Martha has pressed her nose to the windows of Mr. Ingram’s mansion. The Invisible dine late, she tells us, but they light neither candle nor lamp. There is no fire even, but they seem warm enough in their cambrics and silks. The ladies’ throats and wrists are bare. They drink wine as red as rosehips from silver goblets. The china is blue and white, thin as a blade, and the table is laid with many dishes. They eat roast meats with French sauce, fillets and cheeks and sirloins, veal fricassey, veal ragoo, snipe, partridge, wheatears, lark livers simmered with cloves, blanched lettuce, white milk-bread, flummery and posset, clary fritters, heaped bowls of gooseberries and mulberries and quinces, sweetmeats colored with spinach and beet and delicately fashioned into multitudinous shapes.

But who waits at table? we want to know. Who delivers the food? Who cooks it?

Martha has seen no Invisible footmen standing to attention, no butchers or vintners at the kitchen door. The Invisible, she insists, are all wealthy. There are no Invisible maids or carpenters or shopkeepers. The Invisible do no work.

But how can they live without the poor to serve them? we ask.

What about the puddings? says Eliza. Are they spiced? Do they wobble? Are they eaten hot or cold?

There are baked puddings and boiled puddings and set puddings, says Martha. Wonderful domed and turreted puddings, like palaces. Thick with candied cherries and angelica. The custard is yellow as buttercups.

They sit at table for hours, she tells us, but they talk more than they chew. They don’t gobble their food or help it to their mouths with their fingers, hunting down any fragments that fall and cramming them back in.

Tell us about the meats, we say. Tell us about the cream. Tell us about the apricots and persimmons, the roast swans and haunches of venison. Tell us.

Englyn

We are enjoying a kind of fame. In other districts the gossip is of Martha. The Ingrams are mentioned in a number of sermons. The Dissenters make it yet another opportunity to talk of ale and tithes. Owen Owen composes an englyn on the subject of the Invisible that is perhaps not up to the standard of his early and most beautiful work, but we admire its wisdom, and one particularly melodious alliteration, and some of us learn it to recite to our families as we sit beside our hearths.

Markets are visibly better attended and at first we are grateful. But many of the newcomers spend only time, which they use to query and argue, cast aspersions, search behind walls and under trestles, inside calf cots and pigsties.

If anyone asks what makes us so interesting, we have no answer. We cannot explain the Invisible’s curiosity. Some of us speculate it may be convenience, a matter of location. Some of us wonder if the attention is always kindly meant. Do they wrinkle their noses as they walk past us? Wave their lace handkerchiefs to clear the air? Do they avert their eyes from our misshapen bodies and pocked faces?

Mr. Ingram has a gold pocket watch. He consults it more often than is strictly necessary for someone who has no appointments to keep.

Ribbon

Some of the young people—Naomi Price and Megan Prosser and their tittering friends, plus one or two lads who are sweet on them, and Mot, the Prices’ brindled cattle dog—have taken to aping the behaviour of the Invisible. They practise walking in no special direction and raising their eyebrows while others labour. They affect amazement at sickles and stooks and handlooms and potherbs and piglets. The girls have acquired a silk ribbon that they pass about between them so that one or another, usually Naomi, can wear it in her hair every day. They hold their skirts out of the mud, in the manner of Miss Ingram, and fan themselves with sprays of hawthorn.

They have developed a sudden passion for knowledge, pestering Martha with questions. She indulges them until she tires or runs out of observations, then she shoos them away like so many finches. The next day they flock back, nudging and giggling, as at their first day of dame school. Martha tuts fondly and repeats yesterday’s lesson.

We think it harmless enough until they neglect their work. Three times, John Protheroe has to fetch his boy back to the forge. There is a great deal of shouting and a coulter is spoiled. Megan judges herself too good to dip rushes, while Naomi protests that stitching or churning will roughen her hands. The Prices are accustomed to their daughter’s airs, but she has corrupted the once-faithful Mot, who now slinks away from his duties at every opportunity to bury his head in Naomi’s knees and sigh as she folds his pretty ears into a bow.

The Ingrams should know better than to encourage such foolishness, we say to Martha. You should know better.

And when some of us point out that young folk rarely need encouragement, no one listens.

We must keep them close to home, we say.

The dog can be tied up, but our children need another solution. We give them more chores, more responsibilities, make sure they are too tired for mischief.

For a time, we think things back to normal. But the Protheroe boy wears a look of discontent as he works the bellows, and young Preece leans daydreaming on a shovel, next to the lime he should be spreading. As for Naomi, she has declared she will never marry. She would rather stay a spinster, she says, than grow red-cheeked and loose-waisted with a man whose favorite subject is the pigs he smells of. She can be seen rehearsing for her preferred future, strolling alone through marble halls or colonnades of pleached limes, her nose in the air and a frayed gold ribbon trailing behind.

Notes

Tylwyth Teg—not fair and not people

Twrch Trwyth—the cursed but well-coiffed prince boar

Englyn—a short and obedient verse

Haf bach Mihangel—the little summer that we enjoy about Michaelmastime, when we must pay our rents

Milfyw—the plant called by Linnaeus Luzula campestris; when it appears, we read poetry to the cows

__________________________________

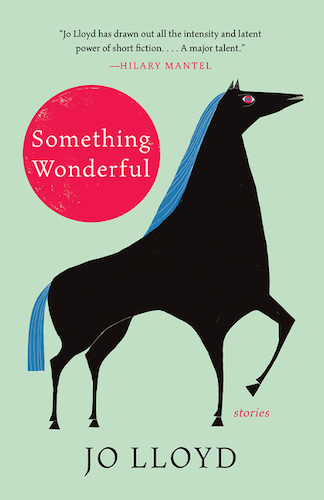

Excerpted from Something Wonderful: Stories by Jo Lloyd. Published with permission from Tin House. Copyright (c) 2021 by Jo Lloyd.