The Interview that Became Henry Kissinger's "Most Disastrous Decision"

How Oriana Fallaci Became the Most Feared Political Interviewer in the World

The encounter that seals Oriana Fallaci’s global reputation as a political interviewer is her interview with Henry Kissinger, the architect of Richard Nixon’s foreign policy. In 1972, Oriana requests an interview and is surprised to be given the go-ahead almost immediately. Kissinger has read her piece on General Giáp and is curious to meet her. He receives her on November 4 in his office at the White House for less than an hour, during which they are continually interrupted by phone calls and urgent requests for his signature. The interview ends earlier than expected because Kissinger is called in for a meeting with the president. After a long wait, she receives the message that Kissinger has departed with Nixon. If she would like to continue the interview, she will have to wait a month. Oriana declines: “It wasn’t worth it. What would have been the point of confirming a portrait I already had in my hands? A portrait made up of conflicting lines, colors, evasive answers, reticent statements, irritating silences?”

The problem is that she doesn’t like him. “What an icy man! During the entire interview, he never altered his blank expression, his ironic, hard look. He never altered the monotonous, sad tone of voice, perfectly even toned. Usually during an interview the dial on the tape recorder goes up and down according to the person’s tone of voice. In his case it remained unchanged, and, more than once, I coughed intentionally just to make sure it was working.” They discuss Vietnam, obviously. Oriana wants to push him to admit that the American withdrawal was a defeat and that the war had been pointless.

Then she moves on to more personal questions, for example about his reputation as a ladies’ man. But the quote that will make the interview famous is his answer to a more innocuous question. She asks him how he explains his popularity. At first he declines to answer. Then he gives in to her line of questioning: “The main point arises from the fact that I’ve always acted alone,” he says. “Americans like that immensely. Americans like the cowboy who leads the wagon train by riding ahead alone on his horse, the cowboy who rides all alone into the town, the village, with his horse and nothing else.”

After being published in L’Europeo, the article is reprinted in several American newspapers and read all over the United States, where it becomes a scandal. Nixon is not at all pleased by the cowboy metaphor. Kissinger tries to deny that he has said these things, but he is contradicted by Oriana, who has a recording. Years later in his memoirs, Kissinger will confess that this interview was one of the most disastrous decisions of his career. Oriana, too, is irritated by the reach of the scandal. “Don’t make me talk about Kissinger!” she will say during an interview at an American college in 1981. “I did that interview in 1972, and ever since, both of us have been questioned endlessly about it. If we’d run off and gotten married, we wouldn’t still be asked about it to this day.”

After this incident she is crowned as the most feared political interviewer in the world. She can choose her own subjects. She keeps the number down to fewer than twenty per year because each meeting drains her completely. She prepares assiduously, reading every scrap of information that exists about the person. The ingredients are always the same: careful research, impertinent questions, theatrical setup. Like the boy in the famous folktale who cries out that the emperor has no clothes, she is intimidated by no one.

In 1974, when she publishes Interview with History, a book containing her most famous profiles, she dedicates it to her mother: “Practically speaking, this is a book about power. A libertarian book about power. My mother, in her innocence, does not understand why there should be a man or a woman up there who decides what should and shouldn’t be done. Do you understand? This is the anarchic attitude of the boy in the story. And mine.” The book is an extraordinary success, the first of her series of worldwide best sellers.

*

In her interviews, Oriana articulates her lofty view of the journalist’s role. She considers herself a witness, a stand-in for the public, and this is enough to make her feel that anything is allowed. She asks very direct questions, and, if these are deflected, she returns to them. She often asks her interlocutor to repeat an answer in order to be sure she has understood it. If something is unclear, she asks for a clarification. She speaks simply and doesn’t allow herself to be drawn into the obscure language of politics and politicians. “My mother used to say, ‘Oriana, what you write has to be understood by everyone; don’t try to complicate things.’ I always followed her advice. Whenever I interview a head of state or a prime minister, I don’t allow myself to play the game of politics, of sociology.”

She’s never detached. She undertakes each meeting with the same passion and radical approach: “In my interviews I don’t act only on my opinions but also on my emotions. All of my interviews are dramas. I involve myself even on a physical level.” She doesn’t believe in objectivity: “When I take the subway in New York and see ads for newspapers that claim ‘Facts not Opinions,’ I laugh so hard the whole subway car shakes. What does that mean? I’m the one interpreting the facts. I always write in the first person. And what am I? I’m a human being!” She claims the right to be fully present in her interviews, a person with her own ideas and impressions. An American colleague confirms this: “If I’m a painter and I’m painting your portrait, don’t I have the right to paint you as I wish?” But there are rules: “I write everything they say, but I don’t publish things that slip out in conversation. If they say, ‘Don’t print this,’ I don’t. It’s a pact, a contract. If not, what are we? Word thieves? I respect the contract. But I don’t allow any of my subjects to review my articles before publication.”

Her interviews can go on for four to six hours. “In those hours I burn so much energy that I lose more weight than a boxer in the ring.” Whenever possible, she likes to meet the subject a second time in order to confirm her first impressions. She also works tirelessly on the logic of the article. She transcribes everything, checking her translations with a dictionary, then puts her text together like a play, cutting and pasting, crafting the rhythm and flow.

She doesn’t like it when her colleagues, especially in the United States, praise her interviewing skills. She considers herself a writer. She argues that her interviews are stories, with characters, surprises, conflict, and, especially, suspense: “My interviews are the interviews of a writer, conceived by the imagination of a writer, conducted with the sensibility of a writer.” They require space in the newspaper, pages upon pages, a fact that drives her editor, who is under strict orders not to cut them, to despair. Each interview represents a point of view, for or against something. Sometimes she makes a mistake or is derailed. It happens, as she will admit later, when she interviews the Palestinian leader George Habash, the founder of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. Habash is a supporter of international terrorism, but Oriana likes him, despite her better judgment. He moves her with his stories about working with refugees and setting up a clinic in Jordan (he is also a doctor). When she realizes her error of judgment, much later, she admits it publicly. This is a risk when one practices passionate journalism, as she does. Oriana knows this and is not afraid to admit it: “My naïveté is a quality I value intensely because it is born from a faith in humanity and love for my fellow man. This love and faith swell up in me whenever I see suffering.”

For her, an interview is never neutral. It is an encounter, a collision, sometimes a love story. This exchange with a colleague regarding her methods is especially illuminating: “‘Do you go into your interviews with the powerful men of the earth with the intention of berating them?’ ‘Of course not! I go in with the desire to understand them.’ ‘Without preconceptions?’ ‘No, I have preconceptions, of course. But because I’m a reasonable human being, I can change my mind.’” She doesn’t like to be described as a journalist who is feared. “If they’re afraid of me, that’s too bad. I need a partner. An interview is like a duet in an opera.”

She doesn’t use insults as a weapon. When she is about to strike, she warns her interlocutor: “When I have to ask a brutal question, I always say, ‘Now I’m going to ask you a brutal question.’ I don’t write it down each time because it would be boring for the reader.

My questions are brutal because the search for truth is a kind of surgery. And surgery hurts.” She is frequently accused of combativeness, which she considers merely courage, as she explains to an American colleague: “Most of my colleagues don’t have the courage to ask the right questions. I asked Thiêu, the dictator in Saigon, ‘How corrupt are you?’”

__________________________________

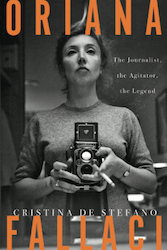

From Oriana Fallaci: The Journalist, the Agitator, the Legend by Cristina de Stefano, trans. Marina Harss courtesy of Other Press. Copyright 2017.