The Intersectionality Wars: Does the Term Even Mean Anything Anymore?

Jennifer C. Nash on the Labor of Black Feminists

At the 2014 American Studies Association (ASA) conference, a panel entitled “Kill This Keyword” asked: “Can critical leverage, incisive edge, be returned to commonplace terms, or to the ideas to which they refer? What terms have fallen out of favor that might be reanimated in the face of the demise of another?” Panel members were invited to reflect on widely circulating scholarly terms like “precarity,” “neoliberalism,” and “affect,” and to determine if these terms should be “killed”— banished from our scholarly lexicon—or “saved.”

Nothing generated more anxiety than “intersectionality,” which was immediately declared dead. Moments after a collective performance of intersectional fatigue, a scholar voiced discomfort with “killing” intersectionality because to do that would be to “kill” black feminism, or perhaps even to “kill” black woman as object of study. The room grew quiet at the prospect of symbolically killed black women. As intersectionality slipped into black feminism slipped into black woman, the analytic moved from dangerous to desirable, from peril to promise, and the audience that had been quick to kill had been convinced to rescue.

The term “intersectionality wars” describes the discursive, political, and theoretical battles staged in this scene. Indeed, as this ASA encounter makes visible, debates about intersectionality all too quickly become referendums on whether scholars are “for” or “against” intersectionality (rather than attempts to refine, nuance, complicate, or even think through intersectionality’s contours and migrations). And debates about whether one is “for” or “against” intersectionality almost always seem to become referendums on whether one is “for” or “against” black feminism, and perhaps “for” or “against” black woman herself.

These slippages—between black woman and black feminism, between intersectionality and black woman, between intersectionality and black feminism—animate the intersectionality wars because they ensure that discussing intersectionality’s critical limits is always already to debate racial politics and allegiances. Undergirding the ASA scene, and the intersectionality wars more broadly, are the affective dimensions of the prevailing narrative I described earlier, one where intersectionality is under siege and must be saved, one where a group of critics who are characterized in various ways—ranging from misguided careerists to anti-black or anti-black feminist—have made it a mission to undermine black feminists’ intellectual contributions.

I am drawn to the term “intersectionality wars” because of its echo with feminism’s other wars, most particularly the sex wars. Waged in the 1980s, and reaching a feverish pitch around the time Barnard’s 1982 Scholar and Feminist Conference focused on “pleasure and danger,” the so-called sex wars seemed to be battles over pornography. These “wars,” though, were about much more than pornography; the “sex wars” were bound up with accusations of policing sexual minorities and attempts at censorship, especially in light of Catharine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin’s attempt to pass anti-pornography legislation and the Feminist Anti-Censorship Taskforce’s decision to file an amicus brief in American Booksellers v. Hudnut.

I am drawn to the term “intersectionality wars” because of its echo with feminism’s other wars, most particularly the sex wars.

Even the casting of widely circulating and complex debates about pornography as a “war” suggests that feminists defined themselves exclusively as “for” or “against” pornography, eliding myriad feminist work that sought to stake out a complex analysis of pornography’s meanings, pleasures, and cultural significance. Similarly, the intersectionality wars seem to be fights over intersectionality’s meanings, circulations, origins, “appropriation,” and “colonization,” but these fights are actually battles over the place of the discipline’s key sign—black woman—in the field imaginary. These wars are fights over questions like: Will black women “save” so-called white feminism with an insistence on intersectionality as the analytic that will free feminism from its exclusionary past and present? Will black women undo feminism with a demand for a complex account for difference? Will black women’s efforts to discipline the field finally—and even redemptively—exculpate the field from its racist past? What is intersectionality’s ultimate theoretical and political goal?

If the “sex wars” were rooted in the sexual culture—and sexual panics—of the late 1970s and early 1980s, the intersectionality wars are relatively recent battles, rooted in intersectionality’s “citational ubiquity,” its movement across disciplinary borders, across administrative/intellectual boundaries, and across academic/popular boundaries. I date the intersectionality wars to intersectionality’s institutionalization, to the rise of Kimberlé Crenshaw’s articles “Mapping the Margins” and “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex” to near-canonical status, and the movement of intersectionality to the center of women’s studies. I also date it to intersectionality’s circulation in popular feminist conversations as a way of signaling a critical practice attentive to (certain forms of) difference, as a way of disciplining so-called white feminism and white feminists, and as a strategy for naming ethical practices of feminism. As more scholars have laid claim to intersectionality, as more disciplines have come to value—at least rhetorically—intersectionality, the intersectionality wars have escalated, with black feminists increasingly stepping into the fray to defend the analytic from imagined misuse and abuse, from improper circulations and devaluations.

Like the sex wars, the intersectionality wars have been waged in contentious ways. The sex wars were played out through public confrontations—debates over Barnard’s “Pleasure and Danger” Diary, battles over the proposed anti-pornography legislation, civil rights hearings led by MacKinnon and Dworkin, and protests against anti-pornography legislation; the intersectionality wars have been played out in increasingly contentious scholarly battles waged at conferences, in journal articles, and at myriad symposiums celebrating intersectionality and its interdisciplinary cache.

Like the sex wars, the intersectionality wars have been waged in contentious ways.

In describing these battles as contentious, I am particularly drawn to considering the tone of these scholarly debates as the location where the deep antagonisms of these battles are most visible. My turn to form—and to tone—is indebted to the work of Janet Halley, who argues that “political ideas have prose styles” and that “you can find out something about your political libido by feeling for whether you are turned on or off by a political idea’s way of addressing itself to you.”

The intersectionality wars are produced through particular kinds of appeals that work on the reader’s “political libido” through language that underscores the violence inflicted on intersectionality by “critics.” In other words, these “wars” are waged through exposure: black feminists reveal the violence of critics’ work through language that is itself forceful. For example, Brittney Cooper describes Jasbir Puar’s work as an “indictment of intersectionality.” Nikol Alexander-Floyd argues that Leslie McCall’s widely cited article “The Complexity of Intersectionality” “disappears black women and their scholarly contributions; more pointedly, her analysis does violence to the progenitors of intersectionality by subverting their aims and objectives.” She also warns, “Barely a decade into the new millennium, a new wave of raced-gendered occultic commodification is afoot, one focusing not on black female subjectivity per se, but on the concept of intersectionality.” Sirma Bilge writes, “Intersectionality, originally focused on transformative and counter-hegemonic knowledge production and radical politics of social justice, has been commodified and colonized for neoliberal regimes.” The Crunk Feminist Collective notes, “Intersectionality without women of color is a train wreck. Call us parochial if you want to, but we should remember that in the case of both these theories, they grew out of the lived political realities of marginalized people.”

I put these distinct quotes next to each other to call attention to something that permeates black feminist entanglement in the intersectionality wars: the language used to describe and capture the violence performed by intersectionality’s critics—disappearing, commodification, colonization, and “train wrecks”—suggests that criticism is a violent practice. The impulse undergirding these readings of intersectionality’s critics is prosecutorial: it exposes, indicts, and condemns. This reading practice works on readers’ “political libido” by representing an intersectionality under siege, rendered vulnerable by the labor of critics, and ultimately salvaged by the labor of black feminists themselves.

The labor of black feminist scholarship, then, is to incite the reader to protect intersectionality from a set of forces—colonization, appropriation, gentrification—that are undeniably violent. It is intersectionality’s vulnerability that demands a protective response. In noting that this language works on the “libido,” my intention is not to suggest that it produces only political arousal—it might just as easily produce disgust, boredom, or unhappiness. Rather, my interest is in how these battles are waged in a language that reproduces intersectionality’s vulnerability in the service of enlisting readers in the battle to preserve and protect the analytic. If the intersectionality wars are contentious, what precisely is being fought over? What are the battles that are unfolding under the sign of intersectionality?

![]()

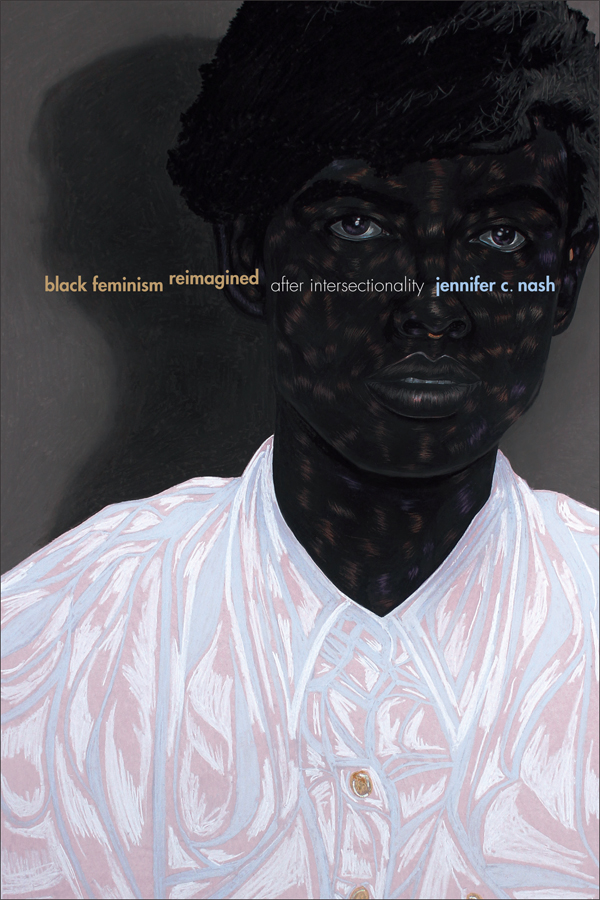

From Black Feminism Reimagined by Jennifer C. Nash, courtesy Duke University Press. Copyright 2018 Jennifer C. Nash.

Jennifer C. Nash

Jennifer C. Nash is the Jean Fox O’Barr Professor of Gender, Sexuality, and Feminist Studies at Duke University. Her most recent book, How We Write Now: Living with Black Feminist Theory, will be published by Duke University Press in September 2024.