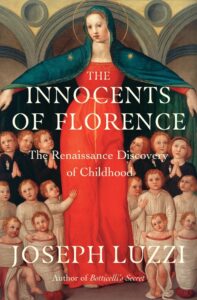

The Innocenti: The Renaissance-Era Orphanage in Florence

Joseph Luzzi on the Abandoned Children of 1400s Italy

In the summer of 2019, I had lunch in Florence with a friend, an art historian, and afterward we decided to take a walk. Along the way, we passed by the Piazza della Santis-sima Annunziata and the structure that runs along its eastern flank. It was a hot, clear afternoon, the sky the same deep blue as the background to the swaddled terracotta babies by Andreadella Robbia atop the Hospital of the Innocents, or Innocenti, as it is called.

With nine perfectly symmetrical arches as lovely as a swan’s neck, this orphanage had long stood out to me for its architectural splendor, which has inspired many to call it the first Renaissance building (Plate 1).

Whenever I stood in the piazza, which is just a few minutes’ walk from the Duomo yet somehow buffered from its tourism and commerce, I felt calmed, as the orphans must have felt after all the chaos and drama they had left behind. I admired the Innocenti’s mission and vaguely knew some of its history, but it was always more of a backdrop—just another ambient visual triumph in a city prodigal of beauty.

The surge of their salvaged lives coursed through me like an electric current.

Because the piazza was unusually empty, my friend and I decided to stop at the building’s loggia and take in Filippo Brunelleschi’s exquisite design. For a long while, neither of us spoke. We just gazed, and I began to feel the history of the Innocenti in a way I hadn’t before.

I had always taken a parent’s love for granted because it surrounded me at every stage of my life. But my father had long since passed away, and my mother, a once-vigorous woman who could pluck three chickens and skin a rabbit in the time it took to load the dishwasher, was approaching ninety.

The children of the Innocenti enjoyed no such luck in the parental lottery. Some were abandoned because they were the fruit of an illicit affair or an act of sexual violence. Others, because their parents couldn’t feed them. Others still, because their mother or father had fallen ill or unexpectedly died.

Suddenly, the ghosts of all those unwanted children seemed to fill the piazza. They were no longer the generic heirs of della Robbia’s anonymously adorable infants. The surge of their salvaged lives coursed through me like an electric current.

Not long after my visit to the Innocenti, I spent the morning with my mother at the home where she had raised me and my five siblings. My wife took a picture of the two of us along with our youngest daughter, Sofia (Plate 2). Not surprisingly, all my mom’s attention in the picture is focused on Sofia. More unusual, my ungovernable whirlwind of a two-year-old looks pleased as punch, smiling docilely for the camera and exuding the joy that comes from feeling loved and safe. That was her nonna’s effect on children.

An immigrant from a poor village in southern Italy, Yolanda Luzzi had no public life to speak of, barely having worked a day outside the home in her entire life. Even her Italian identity card from 1951 listed her occupation as casalinga, housewife. Yet she and the Innocenti shared a legacy: both had served as guardians of the vulnerable, caregivers of last resort.

A decade or so earlier, my late wife, Katherine, had died in a car accident. She was eight and a half months pregnant, and our daughter, Isabel, was rescued by an emergency cesarean. That night in Vassar Brothers Hospital in Poughkeepsie, as the black waves of grief engulfed me and Isabel rallied against the odds in the neonatal unit, my nearly eighty-year-old mother announced to our gathered family that she was going to help me raise my daughter.

I too had produced an “innocent”: a helpless Isabel depended entirely upon my mother’s unconditional love as I struggled to meet her needs while rebuilding my life as a widower and single parent.

For the next three years, she performed tasks and activities that would have exhausted a twenty-year-old, as she waged her own private battles with tinnitus, insomnia, arthritis, and a weakened heart given temporary reprieve by a quadruple bypass. She changed diapers, prepared meals, and fed a tired and hungry baby, though she was by then a grandmother and great-grandmother many times over.

Isabel wasn’t the only person she had to care for. With my life at ground zero, I needed as much help as my infant daughter. Like the Renaissance parents who failed to care for children they abandoned, I too had produced an “innocent”: a helpless Isabel depended entirely upon my mother’s unconditional love as I struggled to meet her needs while rebuilding my life as a widower and single parent.

We like to say that it takes a village to raise a child, and the civic and political groups who created the Innocenti understood this intuitively. The Renaissance is often mythologized as the age of individual titans, like the obsessive Michelangelo, who singlehandedly painted the Sistine Chapel lying on his back, the endlessly curious Leonardo, who filled notebook upon notebook with drawings of anatomical structures and fantastical inventions, and the monomaniacal Brunelleschi, who designed the Duomo with no formal training in engineering.

That “great man” view of history can obscure the more collectivist and community-based ethos that defined the Renaissance, especially in its urban cradle, Florence. It took a team of painters—Masolino and Masaccio in the 1420s, and Filippino Lippi in the 1480s—to complete a single massive work: the Life of Saint Peter fresco cycle in Florence’s Brancacci Chapel, which Giorgio Vasari described as a kind of art school that drew Botticelli, Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael, among others, to study its revolutionary approach to the human figure.

Similarly, later works by an artist as renowned as Botticelli were often as much the work of his bottega, workshop, as of the maestro himself. Nowhere was that communitarian spirit more prominent than in the complicated project of establishing the Innocenti.

The first home in Europe devoted exclusively to caring for unwanted children, the Innocenti took in its first infant in 1445 and would go on to care for close to 400,000 children. It is often referred to by the generic term orphanage, but technically it did not become one until 1890, when the newly formed Italian government made it an official public charity and changed it from an ospedale, hospital, to a brefotrofio, orphanage.

It was the place where children were abandoned, sometimes because they were in fact orphans with no living parents, but more often than not because one or both parents were unable or unwilling to provide for them.

The Innocenti was originally called a hospital because it provided basic medical services for its children through its affiliate, the Hospital of Santa Maria Nuova, the largest health care provider in Florence from the Middle Ages to the present. Beyond its official terminology, the best way to think of the Innocenti for the bulk of its five-hundred-year history is as a foundling home: it was the place where children were abandoned, sometimes because they were in fact orphans with no living parents, but more often than not because one or both parents were unable or unwilling to provide for them.

Since the term foundling home can come across as remote and antiquated, I will refer to the Innocenti as an orphanage in the broadest sense—a place for unwanted children whose care became a matter of state concern.

The idea for the Innocenti began in medieval times and required more than a century of plans, donations, and negotiations before the arrival of its first trovatello, foundling. Its protracted, contentious genesis is not surprising: terms like child and childhood are complicated ones with a vast array of meanings and competing interpretations. One observer even described the history of childhood as a “nightmare from which we have only recently begun to awaken.”

In the landmark study Centuries of Childhood (1960), the French scholar Philippe Ariès famously argued, “In medieval society the idea of childhood did not exist . . . as soon as the child could live without the constant solicitude of his mother, his nanny, his cradle-rocker, he belonged to adult society.”

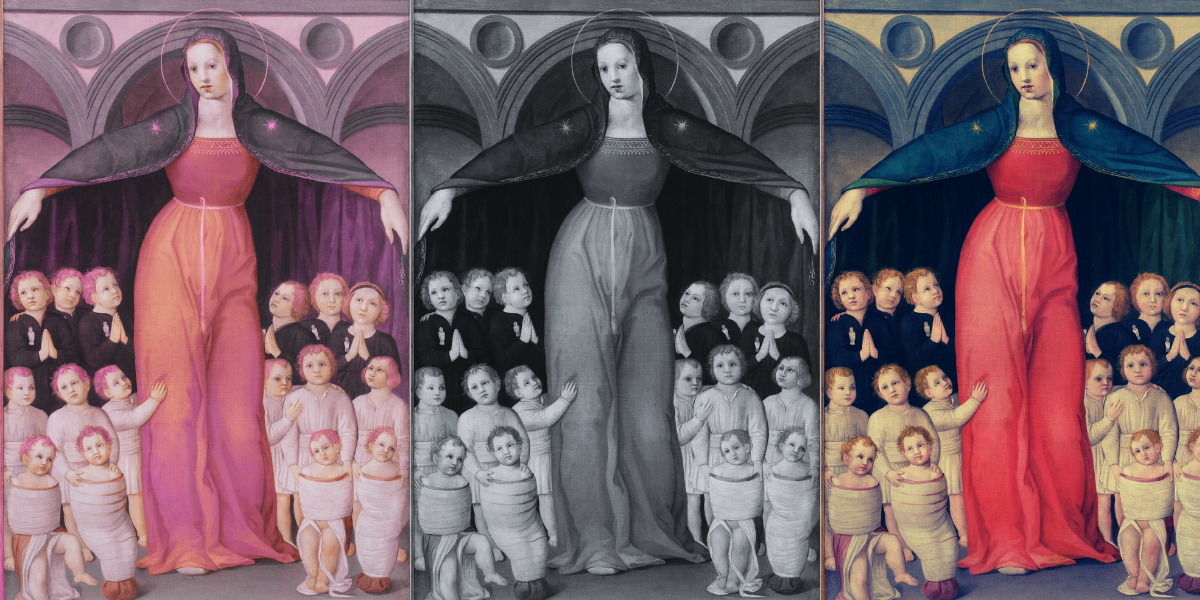

To prove his point, Ariès cited the many old-looking Jesuses filling the canvases of painters like Duccio (Plate 3), writing, “Medieval art until about the twelfth century did not know childhood or did not attempt to portray it.” Ariès might have looked to medieval literature for a similar sentiment: in his philosophical treatise The Banquet (1304–07), Dante ignored infantia, infancy, altogether and focused instead on adolescentia, adolescence—the ages of eight to twenty-five—when the presumably unformed being developed into adulthood.

Ariès’s notion that the concept of childhood did not exist in the Middle Ages, and that it was invented in the Renaissance, is a hotly debated one.

Ariès wasn’t saying that medieval parents didn’t love or dote on their kids as we do today. Rather, he wrote, they lacked an “awareness of the particular nature of childhood” and of what “distinguishes the child from the adult.”

Ariès’s notion that the concept of childhood did not exist in the Middle Ages, and that it was invented in the Renaissance, is a hotly debated one. The artistic representation of children in paintings may give us clues, but certainly not conclusive evidence or proof of how people of a given time thought about children and how children themselves construed their own identities.

Yet one thing is undeniable: the Renaissance witnessed an explosion of interest in children and the family. Thinkers rejected the medieval view that children were imperfect little adults moored in a transitional state between infancy and maturity that required constant Christian instruction. Theorists including the polymath Leon Battista Alberti and his fellow humanists wrote influential tracts on what we might call home economics: the organization and structures of domestic life along with the roles and responsibilities of the family unit, including the previously ignored category of children.

From our perspective today, these books contain many blatant inaccuracies. For example, Alberti claimed in his Book on the Family (1433–40) that illness could be passed on by “bad milk” from wet nurse to child, a dubious notion echoed by Matteo Palmieri in his widely read On Civic Life (1431–38), which argued that the more “ethnic” the wet nurse, the more unworthy her milk: “what worse thing can one do than subject the infant to the breast of a Tartar, Saracen, Berber, or other bestial and crazy nations?”

Less affluent kids knew nothing beyond work and survival.

Despite their flaws (and occasionally raging xenophobia), these and other works, like Francesco Barbaro’s On Wifely Duties (1415), offered a new philosophical understanding of the family, especially its youngest members. Florence’s best minds increasingly believed that children of all classes and backgrounds should cultivate certain essential human qualities: a moral compass, an appreciation of art, a sense of meaning and purpose and the tools to acquire it. They pushed this agenda in the face of countless obstacles.

Back then, only children of the wealthy and highborn enjoyed the perks of what we now consider a normal childhood—school, play, and the freedom from having to provide for one’s own care and upkeep. Less affluent kids knew nothing beyond work and survival. Childhood leisure and the long, slow path to maturity it now encompasses for many were the rarefied province of Renaissance one-percenters.

Nevertheless, the unequal, stratified society of Renaissance Florence—which had two forms of currency, a gold florin for the wealthy and their luxury goods and a silver or “little florin” for the working class and their everyday purchases—dedicated itself to the protection of unwanted children. To be a true Florentine, the feeling went, one had to be an active, engaged, and patriotic citizen, beholden to no less than the ultimate Christian authority. This sense of civic and religious responsibility toward the least fortunate was measured as carefully as a business’s gains and losses.

As one scholar observed, “Every Tuscan counting-house had an especial account in its ledger, il conto di Messer Domeneddio [Master God Almighty’s Account], in which the part of the profits laid aside for charity was duly inscribed, and every rich merchant, however unedifying his life or cynical his opinions, felt bound to endow or support some charitable institution.” The Innocenti was the result of this moral calculus, as its abandoned children held up a spiritual mirror to a society suspended between the eternal joys of heaven and the fleeting seductions of secular life.

In 2022, my mom finally succumbed. In the months that followed, I was surprised, even astonished, that though I missed her intensely, I found it impossible to grieve or mourn her. Her legacy felt too alive to be associated with death or loss.

At her funeral, scores of family, friends, and community members came to express their love and pay their final respects—the surge of ambient emotion was similar to the one I had experienced during that fateful visit to the Innocenti a few years earlier, when hosts of the infant dead seemed to fill the Piazza della Santissima Annunziata. Casting off their usual morbid sheen, the grounds of the cemetery exuded life as my mom was returned to the earth. I was asked to say a few words about her by her grave, and I ended my eulogy, without knowing exactly why, with Dante’s final verses in The Divine Comedy, when he has a vision of the world held together by cosmic love.

A few months after the funeral, I visited the Innocenti and came across an exhibit that asked visiting schoolchildren to share their thoughts and impressions about the Renaissance foundling home. The responses were as various as one would expect, from random declarations like “Ti Amo, Ettore!” (“I Love You, Hector!”) to heartfelt expressions like “Oggi è un giorno speciale!” (“Today is a special day!”) and “I bambini sono più grandi di quanto pensiamo” (“Children are more grown-up than we think”).

Then there was one that felt dropped from above like a gift from my mom, a spare phrase in block letters and blue ink that repeated my parting words to her from Dante—words that seemed to lay bare the Innocenti’s mission, as it aimed for the heavens while often foundering on the planet Earth of human corruption and thwarted ideals:

l’amor che move il sole e l’altre stelle.

the love that moves the sun and other stars.

__________________________________

From The Innocents of Florence: The Renaissance Discovery of Childhood. Used with the permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton and Company. Copyright © 2025 by Joseph Luzzi.

Joseph Luzzi

Joseph Luzzi is professor of comparative literature at Bard College and an award-winning writer, teacher, and scholar of Italian culture. He is the author of four books and lives in New York’s Hudson Valley.