At the Café du Printemps, whose facade splits the darkness like a green pustule, it’s only over dessert, with the last of the fellow diners gone, that I decide to raise my nose from my plate. The room is filling up with fresh arrivals, card players, drinkers who, most likely, find themselves here every evening. My presence doesn’t bother them, and, like them, I can consider myself an old habitué. The plates, dishes, and lace paper that adorn the table have disappeared, to be replaced by solid glasses of dubious cleanliness filled with cheap wine by a waitress who resembles them. Light falls from two greasy bulbs.

Having ordered a drink, I’m consulting, out of habit, the little notebook that serves as my aide-memoire, still unable to decipher the half-erased name and address, when an argument breaks out among a trio of card players behind me. I turn around, pretending that I have no concerns other than the wreaths of smoke wafting from the bowl of my pipe. A woman seems to be sleeping near the three men, her faded red hair spilling out over her arms folded on the table where two of the players have just abandoned their cards. One of them, looking tense and peevish, eyes ablaze, shouts: You’re cheating Squint! The second one sneers and the black pupils of his eyes gleam with malicious curiosity as he stares at the accused man. The third party—the guilty man—has his back turned to me, but I immediately recognize him from his wretched appearance: the down-and-out from this afternoon. No doubt about it, this gentleman is pursuing me; impossible to take a step on the island without running into him! This character, whose manner and profile would be more at home among a crowd of immigrants on the deck of a steamer than in this neighborhood café, and who seemed so unimportant those few hours ago, now claims my full attention. His calmness and air of debilitation are in sharp contrast with the vociferous clamor of the other two. He has the distinctive look of someone who’s been sleeping rough for a long time, but something in him, which might be called the dignity of impoverishment, raises him well above his neighbors who are blissfully unaware of their own well-dressed mediocrity. He has, this man called Squint, held onto his cards: a king, two jacks, and a queen. And my astonishing impression is that these face cards seem not unrelated to the living beings around the table, not only replicating them in image but also linked to them by other less palpable correspondences. In the very moment that this far-fetched idea strikes me, and as though to confirm it, I’m struck by a maneuver unseen by those involved in the rumpus. A finger of the bony, filthy hand holding the cards slides out the female card, flicking it to the ground where, flipping round, it falls at my feet. Then his hand, still concealed but this time so ineptly that his neighbors can’t fail to see it, reverses the king positioned between the two jacks. And, as though with this final gesture the master of the game has voluntarily sacrificed the sway that he held over his two acolytes, as though he’s cut the thread holding back their anger, a violent scene immediately erupts, so sordid that it’s scarcely fit to be described. Suddenly on his feet, the big man yells, his jaw clenched, hands like clubs sending cards and tumblers flying. The waitress tries to intervene, but the other one, still sneering, stands up in his turn and gives her such a brutal shove that she sprawls on the floor for several minutes, underwear prominently displayed, before groaning and picking herself up. Then the brute, his eyes gleaming with cruel pleasure, as though suddenly seized with inspiration, interrupts his companion, who is hitting out while swearing, and goes one better in the language of the gutter: What!? . . . cheating your friends?

. . . And who’s gonna get his sugarlumps? It’s Mr. Squint, and who’s gonna go woo woo? It’s Mr. Squint. His victim, still sitting, still as limp as he was under the blows, with this ruffian leaning into his face, seems to smile unconsciously and, like a well-trained dog playing along with his tormentors’ game, bays in a shrill voice. Enough already! Open your snotbox! His persecutor, after hawking up deeply and noisily, lets fly a thick gob of spit into his mouth, which is promptly opened wide. It isn’t an easy thing to depict the despicable. Frozen with shame, a sickened witness, I finally manage to get up to flee the scene. As I close the door behind me, Squint’s almost expressionless face appears to be turned in my direction, while the woman, whom I thought asleep, lifts up a face that’s wet with tears.

*

There’s no better remedy for a stomach that’s heaving with disgust than taking great strides to forge a path through the nighttime air. A faint sound in the wake of my footsteps soon warns me to slow down; then, anxious at being followed, I hasten toward the better-lit crossroads on the approach to the bridge. Before I’ve arrived there, a voice suddenly whispers, almost at the back of my neck: Fidibus! Stopping, I recognize Squint’s pitiful features, fifty meters from mine, animated from the chase, badly shaven, and pierced by two oily lights that I can’t lock onto. A remnant of professional pride— and me without a fixed profession!—would make me ashamed to be buttonholed by this individual in broad daylight, but amidst so much darkness aren’t we merely two anonymous silhouettes? What’s more, his voice surprises me. It possesses that particular upper-class familiarity that lower orders mistake for sympathy. Ah, there you are, I say. So they didn’t tear you to shreds?—No, don’t go thinking they’re as bad as all that . . . They’re still obedient even when they’re angry. They’re children . . . Us too . . . He’s panting slightly from having run, but after catching his breath he continues, astonishingly calm: And you, Fidibus, are you obedient? Surprised by the unexpected turn taken by the dialogue and shocked by this vagrant’s presumptuousness, I reply haughtily: How do you know my name?—I know more things in heaven and earth than are dreamed of! he replies, so histrionically that it can only be a quip. And he promptly adds: And if I asked how you know mine? Not for a moment do I think of telling him the circumstances in the seedy bistro in which I heard it. Not out of pity, but because that fracas, I feel, is no concern of mine, not directly. It was, no doubt, merely the link, merely the location of our encounter. Something else is now involved. Perhaps I’m going to learn what it’s all about. Names mean nothing . . . or very little, he continues. But doesn’t the ironical tone of his voice let it be understood that, on the contrary, names and only names are meaningful? They can be changed like a shirt. We can get rid of one that’s disagreeable. Do you want an example? The honorable individual I was talking to when you saw us this afternoon calls himself “The Professor.” His name is actually Snot. Mr. Snot! You can just picture it! . . . Does he hide it because he’s afraid that it’ll get confused with mine, or on account of the disgust it causes when spoken? . . . And then names wear out, get distorted, crumble away. Just as the high and mighty can always rise higher and the low can always sink lower without what’s in the middle shifting, so those two words, Squint and Snot, have emerged from one and the same name. You were never in any doubt about that, were you? Nor that this professor and myself were sort of half-brothers? While speaking he stumbles at the edge of the pavement like a beggar scrounging a handout. I make room for him, and we carry on moving forward, like two old pensioners who can no longer be driven back home by anything, anything at all, save death. We’re swathed in the mist rising from the river. People believe that names don’t mean anything because ever since their far distant origins they’ve been reinterpreted too many times. To stick with my example, I wonder how a name has come to be distorted to this degree! A name that’s so ostentatious, so resonant, ending up with us two bastards! It’s really incredible, isn’t it!?—But what’s this name you’re talking about?—Long ago, this entire island belonged to Ogyges, my respected ancestor . . .—What are you saying? Og . . . Ogyges? Feverishly I pull out my little notebook. This time, the name that I haven’t been able to read becomes clear: Og . . . s, that’s what it is, OGYGES, Rue des Charmes. You have to be careful, the voice resumes after a silence. Right from the start men maintain a wrong idea about existence that very few subsequently try to put right. Fidibus, that still doesn’t mean anything, it could be a borrowed name, it doesn’t seem to correspond to any reality, but as a result of calling yourself Fidibus you’ll end up resembling that long, thin paper thing that anyone can set on fire. Exactly like me, Squint, descendant of the respectable and wealthy Ogyges, little by little I’ve acquired the appearance of this abject scrap of humanity walking along beside you, a little bent out of shape, snot-nosed and filthy . . . Yes, you mustn’t trust words and, even less, appearances, which are all too often determined by words. If it’s an extraordinary thing that down here not one human out of two or three billion is like another, I mean hasn’t arrived at the same point on the journey, some rising higher and higher, others falling lower and lower, a center shared by everyone remains constantly in existence. When will we blow up this unmoving padlock, this dead point, so that in a given moment those higher up and those lower down can join together? . . .

__________________________________

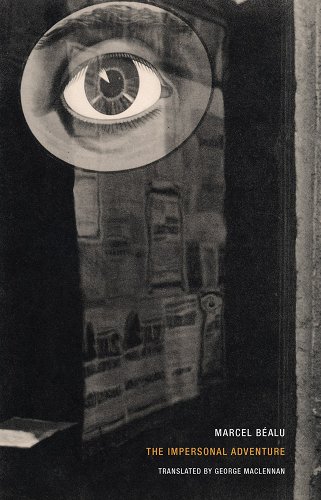

From The Impersonal Adventure by Marcel Béalu (trans. George MacLennan). Used with permission of Wakefield Press. Copyright © 2022 by Marcel Béalu/George MacLennan.