Pork and lemon sole, barely touched, have been cleared from the table. In the restaurant, Sophia and her mother have justified their continued presence with a large, round plate of carpaccio. It sits between them, in the midst of two other, smaller plates. It glistens redly. Neither woman has much interest in it. They have started to grow tired of the ordinary screams chair legs around them give when pushed out for old guests to exit.

I got so angry with him after I read what you wrote, Sophia’s mother says abruptly. She observes the small, empty plate in front of her, traces a finger round its rim. I don’t doubt he brought strange women back to where you were staying while you were on holiday with him, underage. It sounds exactly like him. I didn’t even need to call you and ask. But then I got angry with you, because you never told me. I had to find out about it through your bloody play after I’d promised you not to tell him anything about it.

Sophia looks up. You didn’t, she says. She means this in thanks; she means it as a gesture of hope.

Her mother groans in her chair. I didn’t. I wanted to, and couldn’t. What was I going to do about it ten years after the fact? I kept you with me for almost eighteen years without him interfering and he still managed to ruin it at the very end. There were days when I was staying with him where I couldn’t look at him after reading your play.

In order to read her daughter’s work, Sophia’s mother had printed the emailed script at a stationery shop close to her ex-husband’s home. She had taken it to a cafe selling artisanal bread and iced buns, and gone through it in one sitting. Paranoia had seized her after reading. To think of it lying on the bedside table in the guest room. To think of Sophia’s father finding it there. Unable to imagine anywhere she could hide it safely from his grasp, she had paid £2.90 for her espresso and ditched it in the first bin she saw.

When Sophia’s father had greeted her on her return, she’d felt sure something in the pages she’d read had clung to her. He seemed to smell it on her. Late June. They had been bickering already, but after Sophia’s mother had read the play, a new distance between them had formed; less courteous than the one before, more remote. He liked to pick at it when bored. I must be keeping you away from all your lovers, he’d sulked by the front door one night, after she’d spent the evening out. It had been as though he’d waited for her to come home. The next morning, when he’d seen her hungover, she explained she had been with friends, enjoying sparkling wine and olives in one of their gardens. He had looked pointedly at her, in her unironed cardigan and her house slippers with peeling soles. He had said, What a sweet little way to spend life’s gardening leave.

And the house had turned. It had never been hers, but after reading Sophia’s play, nothing in it gave her comfort. Every object mocked her. Sitting in the kitchen reminded her of what she’d read. Sitting in the living room seemed like an offering of the worst kind. Say she decided to lie on the sofa with a book or a TV show. Her ex-husband would prowl while she did, waiting for a chance to poke at her. Sophia listens with her head bowed. She tries to project silence. From the corner of her eye, she can see her mother’s fingers playing with the serving fork, lifting rounds of raw meat one by one on silver prongs before laying each carmine slice back down with new wrinkles, new folds, until the whole platter has been rearranged, disturbed.

She looks desperate. Sophia wishes she would just cry, so that it would be permissible for her to start as well. Instead, her mother launches another grenade. You’re so thoughtless, she gasps at her daughter, and gathers speed. Did you ever consider what it would be like for me to read all of that while I was in his house? It was so strange, Sophia. I know it’s a play, but all those sex scenes; didn’t it trouble you, writing that? It’s bizarre. Do you want him to love you more? Do you want to be like him? You certainly write like him. Is it because you only saw him twice a week growing up? Because honestly Sophia, I don’t think you have a clue who he is. You’ve never argued with him. You’re doing it now in the safety of your own head.

It’s not him, Sophia says. It’s a feminist play about men like him.

This earns her a reproving glance. It’s not him, her mother mimics, and grips her empty glass of wine. It’s not him. It’s just his book. It’s just his shirt you describe in minute detail for the main character to wear the whole way through. I bought that for him. Were you aware of that? I bought it for your father when I married him, before you were born.

The waiter descends upon the carpaccio, sweating on its plate. Is it not to your taste, he asks Sophia and her mother. Would you like a dessert menu instead? He fusses with the table’s empty water carafe. To Sophia, he is a saviour; he is the second coming of Christ. She asks him sweetly for more water, another cocktail, for wine to pacify her mother. She tells him to leave the carpaccio, but to come back as soon as he can. Her mother glowers at her after he has left.

It’s not very feminist, she says, to write an entire play about your absent father.

__________________________________

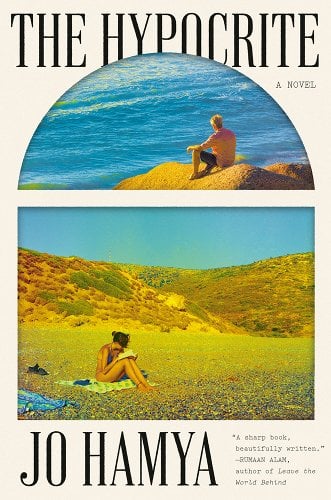

Adapted from The Hypocrite by Jo Hamya. Copyright © 2024 by Joyce Hamya.

Published by arrangement with Pantheon, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Group, a division of

Penguin Random House LLC.