The Hypocrisy of Big Business' Relationship to Cannabis

Lauren Michele Jackson on Race, Weed, and the

Gray Areas of the Legal System

The weed business is booming. So much so that the Green Rush, the surge of commercial opportunities opening up in the sale of weed, will soon be old news. Weed remains illegal under federal law, classified, along with heroine and LSD, as a schedule 1 drug: “defined as drugs with no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.” Nearly two-thirds of states, however, have progressively legalized various types of usage and sale of the drug, pushing its legality into a gray area for much of the nation. As laws have shifted so has public opinion, dissolving stereotypes and taboos and thus expanding the market.

The legal industry was valued at over $10 billion in the US in 2018, estimated to grow by at least $30 billion over the next decade. The jazzman turned pusher—“harsh, predatory, cruel”—has become The Guy, “a white hipster Jesus in a bike helmet,” writes Niella Orr. The Guy is not only the protagonist of the web show turned HBO series High Maintenance following the fictional adventures of an anonymous weed dealer in Brooklyn, he is an archetype, says Orr, “redrawing the public face of pot dealing in America.” The Guy as well as his clientele—white and secure, if not well-off—is joined by beloved stoners Abby and Ilana of Broad City, together the composite for a newly visible class of lady weed enthusiasts.

The truth is even more fanciful than pop culture. Dispensaries now resemble boutique grocery stores, one-stop shops for all things cannabis. Today, the weed business is so much more than kush: portable vape pens and tinctures, “cannabis-infused” salted caramel almonds and sour apple gummy bears. There are weed critics and connoisseurs, weed magazines, weed yoga classes taught by off-duty Equinox instructors, multiday weed conferences, weed weddings and bud bars, 22-karat-gold-dipped one-hitters for $75 and sterling silver grinders for $1,475. Cannabidiol (CBD), a nonpsychoactive cannabinoid found in cannabis, has taken off in a boom of its own, spreading to beauty aisles, pharmacies, juice bars, and pet stores.

CBD providers also operate in a gray region, legally and bodily. While product pushers are effusive over the effects of CBD—promised to reduce anxiety, smooth wrinkles, relieve soreness and pain, mitigate chronic health conditions, and more—skeptics wonder whether companies provide high enough doses to reap the compound’s benefits, or whether CBD does anything at all. “The problem is,” writes the Atlantic’s Amanda Mull, “it’s not easy to know what you’re actually ingesting, or if it’ll actually change how you feel.”

As weed becomes so mainstream as to make puffing passé, it’s become easy to overlook the legality of the matter. Weed is only contingently legal, even in states with fairly liberal positions on possession, and yet the asides journalists and trend forecasters once dedicated to the contradiction of legal weed in America shrink and shrink, if included at all. It becomes less morally relevant to remind readers, consumers, and voters of all the people imprisoned, those who have been convicted and those who simply cannot make bail, for possession of a product now bought and sold at Barneys. As the makeup of the market attests, only certain kinds of people are able to take advantage of the gray, the same kinds of people for whom the law has always been more suggestion than fact.

Obama’s relative lenience—which still saw millions arrested—was a dream state quickly dissolved in 2017 when the Trump administration took the helm. In May 2017, Attorney General Jeff Sessions overrode former attorney general Eric Holder’s 2013 memo, which advised prosecutors against pressing charges for nonviolent, isolated drug offenses. In the 2017 memo, Sessions mandates prosecutors “charge and pursue the most serious, readily provable offense,” warning that “any decision to vary from the policy must be approved by a United States Attorney or Assistant Attorney General.” Marijuana is increasingly decriminalized across the country, yet the number of marijuana arrests is rising. On February 15, 2019, after Congress refused to allocate $5 billion to pay for a wall spanning the length of the 1,954 mile-long border between Mexico and the United States, the president declared a national emergency to seize funds. “One of the things I said I have to do and I want to do is border security,” the president said, “because we have tremendous amounts of drugs flowing into our country, much of it coming from the southern border.”

Even in communities where the drone of presidential xenophobia and racism feels far away, the weed business remains out of reach for black and brown experts who’ve risked the most to learn their craft. Perhaps as an overcorrection due to the tenuous nature of the law, states that have legalized weed for medical or recreational use prohibit people with drug offenses on their record from being involved in a cannabis business in any way. (In my state, Illinois, people with drug felonies are not even allowed to be medical marijuana patients.)

A survey published by Marijuana Business Daily in 2017 found that just 10 percent of respondents who founded or possessed an ownership stake in a cannabis business identified as Latino or African American. “Yes, investors and state governments are eager to hire and license people with expertise in how to cultivate, cure, trim, and process cannabis. But it can’t be someone who got caught. Which for the most part means it can’t be someone who is black,” surmised reporter Amanda Chicago Lewis in a BuzzFeed investigation of racial disparities in the Green Rush. The black and brown people running weed businesses most endangered and devastated by busts, who, like their forebears, created opportunities in the interstices of American propriety in order to get by, are systematically prevented from thriving now that the business is out in the open. Weed, originally criminalized for being too Mexican and too black, now sheds its racial residue without reparations. (Amnesia strikes again.)

Owing to initiatives by local activists, some cities and states have instituted programs designed to improve parity. In California, Oakland’s Equity Permit Program promises at least half of its licenses to Oakland residents who’ve either incurred a weed conviction in the city since 1996 or lived in neighborhoods “with disproportionately higher number of cannabis-related arrests.” Similar, if softer, programs have appeared in Massachusetts, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. Recreational use is still illegal in Maryland, but State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby announced in early 2019 that marijuana possession would no longer be prosecuted in Baltimore. “Communities are still sentenced under these unjust policies, still paying a price for behavior that is already legal for millions of Americans,” she said. And as New York moves toward legalization, New York politicians such as Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Democratic gubernatorial primary candidate Cynthia Nixon have taken the position that the topic of race is inextricable from the topic of legal weed.

During her 2018 gubernatorial debate with Governor Andrew Cuomo, Nixon called legalization “a racial justice issue,” one that ought to “prioritize the communities that have been most harmed by the War on Drugs.” Equity goes beyond awarding licenses, Nixon noted, and includes financial support. She added, “We need to parole people who are in jail for marijuana arrests and we need to expunge their records and use some of this tax revenue [from legal marijuana] for them to reenter [the business].”

Weed is not the only place where legal gray areas grease the way for white entrepreneurs to make it in a big way.

Financially, the barriers to entry into weed commerce look a lot like the barriers that have kept black people from authorized commercial activity since ever. Weed’s first movers are not only white but well-funded. “Getting funded is a bitch,” Wanda James told Vice’s Benjamin Goggin. James, Colorado’s first black dispensary owner, recalls minimum start-up costs upwards of $250,000 when she got her start in 2009. Speaking with Goggin nearly a decade later, those costs had since run up into millions at a minimum, and business owners cannot count on bank loans for a federally illegal pursuit. Even with diversity initiatives at the licensing level, “The only way for black and brown small businesspeople to enter is if you can partner with a large funded white business,” Amber Senter, cofounder of Supernova Women, which uplifts women of color in the weed business, told Goggin.

Additionally, black people and other people of color already in on the legal side of the industry are uniquely burdened with issues of reparations and inequality compared to their white peers. Kadeesha, cofounder of the Metropolitan Collective, told Refinery29 of several “unprofessional” encounters at conferences, instigated by white men who prefer to hit on her than network or discuss issues of race and gender. Rina Cakrani, a Whitman College student, wrote in 2018, “Everyone should feel uncomfortable with how white America is setting up generational wealth off of weed when so many Black and Latino men have been incarcerated and lost their livelihood over the same thing”—yet remorse among proprietors runs low. As David Bruno, leader of a failed bid to legalize weed in Ohio in 2015, told Chicago Lewis, “We’re not a nice society, and there’s not going to be reparations.”

And as white “potrepreneurs” disavow reparations, the mere suggestion of the subject also harms legalization efforts among the general public. In an essay in The Stranger, a white reporter, Dominic Holden, revisits his participation in the campaign for Seattle’s Initiative 75, a 2003 measure to make weed possession the lowest priority for police enforcement. Holden, who didn’t even smoke at the time, advocated for I-75 as a racial-justice matter. Campaign consultants more or less told Holden that this was a bad idea.

Because we could run that campaign, if we wanted. But that campaign probably wouldn’t win. The polling was clear: Those aren’t the messages that convince voters to relax the rules for pot. Nobody made us do anything we didn’t want to do, but we wanted to win, so we mostly shut up about that race stuff.

Instead, I-75 became about saving time and reducing paperwork, empowering cops to focus on “protecting our communities from serious and violent crime.” I-75 passed with the approval of 58 percent of the votes. Legal weed not as reparations but another means for white people to get rich and high.

What started as creative but necessary means to make a dollar away from Uncle Sam’s roving eye have increasingly entered the domain of moguls who act like close-fisted pimps.

Weed is not the only place where legal gray areas grease the way for white entrepreneurs to make it in a big way. At the 2018 State of the Black Tech Ecosystem conference in Chicago, the author and entrepreneur Felecia Hatcher compared extralegal workarounds like jitney cabs and Malachi Jenkins and Roberto Smith’s Trap Kitchen to gig-economy wunderkinder like Uber, Lyft, and Grubhub. Many companies that rely on apps to connect with their customers skirt the issue of licenses and certifications, while black workers caught working around legislation are not so favored. In Tennessee, for example, aggressive cosmetology regulations require hair braiders to be licensed “natural hair stylists” to legally do cornrows, Senegalese twists, or any other popular chemical-free styles. Failure to get a license results in exorbitant fines. The licensing requires expensive instruction at cosmetology school, yet few schools in the state offer such courses. The fines demonstrate no concern for black people and their hair, but rather the felt threat of black labor practices outside the state’s reach.

These appropriated ventures have not disrupted the hustle so much as normalized it. What started as creative but necessary means to make a dollar away from Uncle Sam’s roving eye have increasingly entered the domain of moguls who act like close-fisted pimps. Tech companies wrest away these means in order to further devalue workers by allowing customers to underpay for services. They leave the working poor—usually black and brown folks hanging on to urban life by a thread—with two choices: join and work for pennies, or be pushed out from the trade, from the neighborhood, from the block that used to be theirs. Some go with the first, some with the second, and most choose a bit of both, adding another notch to their hustle and finding other undetected ways to feel a bit free.

__________________________________

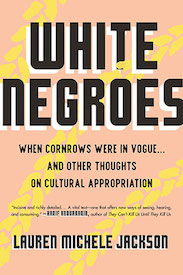

From White Negroes: When Cornrows Were in Vogue and Other Thoughts on Cultural Appropriation by Lauren Michele Jackson (Beacon Press, 2019). Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press.

Lauren Michele Jackson

Lauren Michele Jackson teaches in the Departments of English and African American Studies at Northwestern University. Her writing about race and culture has appeared in The Atlantic, The New Yorker, The Paris Review, Essence, the New Republic, Teen Vogue, Rolling Stone, and New York Magazine, among many other places. She lives in Chicago. Connect with her at laurjackson.com and on Twitter (@proseb4bros).