I don’t remember much of how it all began. I remember flashes: windows flung wide in our apartment, a stuffy summer afternoon, manic frogs from the Vuka. I wriggle between two armchairs and hum—Whoever claims Serbia is small is lying— Papa folds the paper and turns to me, I feel his irritation.“What’s that you’re singing?” he asks. “Oh, nothing, a song from Bora and Danijel.” “Well stop it!” “You bet, ćale.” “Don’t call me ćale, I’m your papa, and damn him to hell!” I don’t know why my papa’s grumpy about the song or who he is, but I have a sneaking feeling it has to do with politics because everybody talks about politics all the time.

We’re packing to go to the coast. For the first time ever my brother and I are going on our own. He’s sixteen, I’m nine. Our neighbor Željka, a year younger than my brother, she’s going too. I want to be exactly like her and I’m so thrilled because my mother and hers asked her to look after me. I don’t sleep a wink all night. On the table between my brother’s bed and mine are our passports. The light’s been switched off and I ask my brother, can I come over to his bed? “Why passports if we’re only going to the seashore?” I whisper. “Papa says if things heat up we’ll go stay with Uncle in Germany,” he says. I don’t get the part about things heating but maybe this has to do with politics, too. I know a thing or two about politics myself, like I call my toy monkey Meso, because my monkey and our president look a lot alike. My brother and I try to imagine Uncle’s life in Germany. He says everybody there is so rich that apartments like ours would be for gypsies. I adore my uncle. He comes every summer, he has a young wife who’s German, people listen when he says something and he smells super nice. This summer his wife brought along a little poodle, Gina, and Granny and Grandpa wouldn’t have it in the house and they said it had to sleep in the shed. There was a huge fight, Granny said she’d poison the fleabag and Papa went to calm them down. Gina stayed in the house. Uncle brought us presents and marzipan, as always. I got a leather volleyball that couldn’t be inflated. My brother got a soccer ball, but he never used it. Soon my brother chases me back to my bed and I spend hours that night thinking about everything.

The bus station in Vukovar smells, it’s early in the morning, I’m sleepy and I’d rather be in bed. Papa’s carrying me, even though I’m big, he carries me the whole way. He’s wearing white pants and a blue T-shirt. We pull apart and kiss, first we make silly faces and then we air-kiss. It’s our thing. There are lots of kids at the station and my brother and I take seats on one of the four buses. Our parents wave and wave, we wave, I can’t see mine anymore but I wave to others I don’t know and they wave back. They smile and call to us to take care, some kids’ mothers cry. Some of them run after the bus to the corner.

I’ve never been on an island before. We’ve been traveling so long I already threw up twice, and I’m not the only one. We even saw the sea a few times from the bus and then it went away behind a mountain. I’m sorry we won’t have time to swim today, but I’m a little scared, too. We swim a lot at the Štrand beach by the river, but it’s shallow there till you go very far out so knowing how to swim doesn’t matter much. I only went to the Danube with my nana who said she swam like a stone, and while I watched the other kids in their inner tubes she only let me get my feet wet and splash my face.

When we finally arrived, I was put in a big room to share with twelve other girls my age. I’d already settled onto one of the beds when Željka came in with the head lady and said we couldn’t be separated. That’s how I ended up in a room with the big girls. I was happy and nervous. Some of them were grumpy about me being stuck in their room because they thought I’d probably spy on them and snitch to the head lady, but we all became friends pretty quick. I didn’t talk much or bug them and I was polite to everybody. They called me “kid,” and I was mesmerized by their spaghetti straps, deodorants, eyeliners, Tajči hairdos. Every evening out on the terrace at the resort we called Villa Drafty we had a disco. I kept being followed around by a boy, everybody said I should dance with him because he was the son of a famous actress. During the day we played Parcheesi and splashed around in the water. One afternoon my brother asked me to take a walk with him along the waterfront and when we got to the end of the pier he shoved me into the sea. I flailed around with my arms and screamed, the water was in my mouth, and he just stood there on the pier, shouting,“Swim, swim!” I don’t know how, but soon there I was on the beach. I burst into tears, my clothes were soaked, and one of my white patent-leather shoes was gone. My brother said: “See, you’re fine.”

That’s how I started swimming.

__________________________________

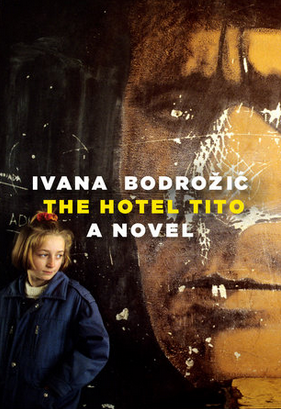

From The Hotel Tito. Used with permission of Seven Stories Press. Copyright © 2017 by Ivana Bodrozic .