I think you weren’t there when, having finished dinner in the hotel restaurant, the young couple went back up to their room to find half a dozen rats running around in every direction. A good half dozen enormous rats hissing: that’s what they saw when they opened the door to their room. Apparently, the wife was already halfway undressed, meaning her husband had already removed half of her clothing in the elevator, I presume that they were going to throw themselves on the bed or on the carpet, but were prevented from doing so, obviously, by the rats. I don’t know if you heard the wife—an Englishwoman—scream, a high-pitched, piercing scream such as only Englishwomen know how to produce. I heard it from my balcony, where I was lying down on the chaise lounge—the chaise lounges they have here are the very definition of comfort. As for the husband—not a peep. It makes one suspicious to hear a woman scream in a hotel, especially a hotel like this one, irreproachable in every way. So I perked up my ears, even if I didn’t get up—it takes me a while to get up, you too I suppose—neither one of us is exactly springing to our feet anymore, are we? The era when we could spring to our feet is over, long over, that goes without saying. I perked up my ears, but there were no other screams. Probably the couple had immediately shut the door of their room and hurried down to the lobby. Just imagine. Rats! At least, that’s what they claimed. Note that, to this day, they remain the only ones to have seen these rats. Neither the management nor the staff, nor even a single member of the rugby team staying here has seen a single rat. The hotel was searched top to bottom, mattresses overturned, a man was posted at every pipe opening, every gutter was inspected, nothing. The rats remained impossible to find: the hotel detective confirmed this fact to me personally. However, he told me, we are bound to believe what our guests tell us, so if our guests tell us that rats, or even alligators, for that matter, have infiltrated their room, we absolutely cannot doubt their word. Despite having been employed here for several years, this excellent detective, Bonneau, a former police officer from Calvados, Normandy, still doesn’t feel that he’s cut out for this job, neither the job nor the country, as he confided to me one day. As for me, I love this country, even though I know nothing about the Portuguese; I come here every spring and from the moment I arrive, the moment I set foot in the airport, the Portuguese become totally abstract to me. Instead I concentrate entirely on the Portuguese landscape, the Portuguese sky, the Portuguese flora, a few magnificent specimens of which are already in view from my balcony. Your room looks out over the outcroppings of schist, isn’t that right, the schist mountains? Men traveling alone almost always opt for a view of the mountains. But if you ever come back, you ought to ask for a room overlooking the river, if I may permit myself to make the suggestion, and once you’re lying down on your balcony—almost a terrace, really—lying on one of those marvelous blue chaise lounges they have here, all you’ll have to do is let your gaze wander over the river, and you will seem to see the caravels of all the explorers parading past, the Diaz, the Caminhos, the Fernandez, the dozens of explorers this country produced, not to mention Christopher Columbus, who was very likely also Portuguese, even if the Italians claim he was Italian, so that Italian and Portuguese historians have been arguing over that wretch for centuries.

Every year I come back to this hotel, always the same room, 44, Room 44 is set aside for me each year, for all intents and purposes; on the first of March I call the manager to notify him that I’m still not dead and that I’m coming, and every time the excellent manager replies that my room is waiting. Room 44, I will have no other. A half dozen rats, so the couple said, as if they had taken the time to count them. The Englishwoman’s scream truly made my blood run cold. Just imagine: she and her husband had just arrived, on their honeymoon from what I’ve heard, married that very morning, and it seems to me that the wife is still extremely traumatized, even though the event happened now twenty-four hours ago. Obviously, despite everything the thought occurs that they could have made it all up, invented the story of the rats to get a free honeymoon, a honeymoon that would not cost them a penny—after all, this hotel is ruinously expensive and those two are awfully young. Young, but rich, noted the hotel detective—which means nothing, it’s surprising what the rich will do to save even a penny of their colossal fortune, what ruses they are capable of, being rich in no way prevents one from being greedy—I knew a woman who replaced her kitchen sponge only once a year, she was covered in jewels but her kitchen sponge was in tatters. We all have our compulsions. The guests who were in the hotel lobby reported that when the couple rushed from their room, overflowing with rats, the Englishwoman wore only a bra, and her head was bobbing left and right frenetically and incessantly, it was impossible to make her stop, impossible to get her to keep her head still. A blond, naturally. As for him—calmer, almost impassive, I’m afraid we have undesirable animals in our bedroom, we heard him say, in the tone of voice one might use to report a bulb gone out. Rats! screamed the Englishwoman. Rats, confirmed her husband soberly. At that point, the entire national rugby team exited the private dining room where all their meals are served, a herd of athletes whose appearance had a radical effect on the Englishwoman, who immediately calmed down enough so that she could be persuaded to slip her blouse back on. Poor thing, what memories she’ll have of her honeymoon! A first class hotel, one of a dozen of its kind in the world. No hair salon, no shop windows full of scarves, as you will certainly have noticed, and not even the tiniest pool. Invisible chambermaids, never one of those disgusting dirty linen carts parked in the hallway. Complete absence of minibars. Just imagine: it’s been only two years since televisions were installed in the rooms, and with the volume set so low that you can’t hear a thing anyway; they conceded to install televisions in the rooms but only with the sound cut off, in order to completely discourage anyone from watching, that’s what the hotel manager hinted to me, with a little smile. Guests struggle with the remote control, call the front desk to indicate there’s a problem with the volume, and are right away transferred to the hotel manager, who makes it clear that there’s no problem whatsoever. If the guests persist in claiming otherwise, the manager, in his most courteous tone, indicates that he has at their disposal an entire list of other establishments they might find more suitable. This is how he puts the guests in their place. No television for me, I told the hotel manager, and instantly, the television disappeared from my room. Meanwhile, the rats. I don’t know, sir, what you think, but personally I’m tempted to believe the rats exist, I imagine them lurking around somewhere in the hotel, ready to emerge at any moment. Yes, I think we should expect to see a horde of enormous rats materialize any second now, probably starving but sufficiently wily to have avoided all pursuit. I think the rats are mocking us, they must have climbed up the banks of the river to reach the garden, then entered the hotel and managed to scramble all the way up to the English couple’s room. Obviously it gives one pause: that the rats would have opted for this particular hotel, exemplary in every way, and then the room of a young English couple on their honeymoon, who for the rest of their lives will associate their wedding night with the abominable sight of rats.

This morning I passed in front of your room, the door was ajar and I saw you in your pajamas, you were holding one of those plastic green mousetraps in your hand that were distributed to us on our breakfast trays, in the event that we would have to contend with a rat. I wasn’t wearing my good glasses, but it did seem to me that it was a mousetrap you had in your hand and that you seemed to have no idea what it was, you seemed perplexed and disoriented, you were the very picture of perplexity and confusion, which made me conclude that you had not heard the Englishwoman’s scream yesterday evening, and that consequently you were still uninformed about the rats. I hesitated to tap on your door and at the moment I had decided I would, you began to hit your thighs with the mousetrap, then your cheeks, then your thighs again, then everything else, the curtains, the bed, the cushions, alternating forehands and backhands, all the way to the chandelier, making it clink. Your swing was sweeping and relentless, reminding me of the best tennis players—here’s a man, I said to myself, who in his youth had perhaps been an excellent tennis player, maybe even a professional, at which point I took the liberty of making inquiries about you to Detective Bonneau. I hope you’ll excuse me this little indiscretion, especially since Bonneau proved to be very evasive on your behalf, merely saying that to his knowledge you bore no resemblance to a former tennis player, then consenting to tell me your name, which naturally is not entirely unknown to me, or to anyone else. It’s been a long time since you’ve given anyone reason to talk about you though, it’s been years since the newspapers have mentioned your name—where have you been all these years? One would have thought you were dead. You smile, but it’s a fact that old people don’t interest anyone, no one wants to hear about old people, and even less to see them in photographs, old people are so depressing, aging is the pits. Although you never sought out publicity, isn’t that right? You always shied away from publicity and awards, skeptical about awards and very reserved, according to what anyone knows about you, which in the end is very little. The last time I saw your name in a newspaper was at least twenty years ago, and after that nothing, not even a line, I lost all track of you. This evening, when I was getting out of the elevator to go to the dining room, I saw you crossing the hall and going toward the gardens, and if Detective Bonneau had not given me your name, I never would have recognized you, to me you were simply dead. Seeing you go toward the gardens, I decided to go there myself to take a walk before dinner, the twilight was beautiful after such a cloudy day, so I went up to my room to fetch a shawl and on my way back down I found myself in the elevator with the Englishwoman. Just imagine: they’re still here. Naturally their room, which must now be crammed with rat poison, was sealed off, so they’ve been relocated to the rugby players’ wing, or so she told me—she was the one who asked to be put there, and even though the wing was completely reserved for the rugby players, of course they found a room for her pronto, where it appears she feels more or less secure. A single room, she added, the shock was so extreme that she asked to be alone for a few nights, with her husband lodged at the other end of the hallway. Marriage is a terrible thing, the Englishwoman also said to me as we reached the ground floor, where her husband was waiting. At least, that’s what I thought I heard, because she spoke very bad French and was smiling in such a way that I may have misunderstood, although I remember that at the end of my own honeymoon—I was twenty years old—I had exactly the same thought: I returned from my honeymoon so horrified by marriage, that as soon as I got back to France I asked for a divorce and never remarried again. For me there was never again any question of marriage. I was very ugly at the time, I’ve always been ugly but at the age of twenty I was at my ugliest. Getting out of the elevator, I greeted the husband of the Englishwoman who, incidentally, appeared rather… well, I don’t know, I don’t know what word could describe the impression the Englishman made on me when he saw me come out of the elevator with his wife, face to face with an Englishman, one never knows what to think. Experience has taught me that when it comes to the English it’s useless to trust either first impressions, or second ones, or so forth and so on—they are always contradictory, and even when one feels one knows an English person, which in reality proves to be utterly impossible, an Englishman is a perfectly unfathomable being who never lets himself be known by anyone, in the end. After greeting him at the elevator door, I was on the verge of mentioning the rats, the rat situation, but at the last second I was prevented, something in his attitude prevented me. He took his wife’s arm and dragged her towards the dining room, where dinner must already be underway. We have a new chef this year and I have no idea what the menu is this evening, even though the menu was brought to our rooms with the newspapers this morning. Yet another novelty—up until last year the menu was only available on a lectern situated in the lobby. I admit that I don’t much like the new way they have of giving us the day’s menu every morning, as if we were in the hospital, as if to remind us—but this probably isn’t their intention—that we should be in the hospital, or that we’ll be there shortly; when to the contrary if we came here, if we made it all the way here, which at our age requires considerable effort after all, it’s precisely because ending up at the hospital is not part of the plan, we’re not content to wait at home until the moment we’re taken there, we don’t expect to sink so low that there will be no other option but the hospital. Every year I arrive here with a sheaf of prescriptions and a pile of medications, every year more prescriptions and more medications. The hotel manager is obviously expecting me to more or less die here in his hotel, or in any case it’s a possibility he can’t afford to dismiss, just as he can’t rule out the possibility that you could die in his hotel, but at least he has the elegance not to ask us to settle our bill in advance. A new chef at the helm, they had a world of difficulty unearthing one, the hotel is after all reputed for its cuisine. I don’t eat much anymore, everything has the same flavor, or the same lack of flavor as it were—I satisfy myself by admiring my plate, I stab a vegetable or two, a piece of fish, everything soon nauseates me—although I ate so much in the past, I loved to eat so much, but without ever gaining an ounce, I was always appallingly skinny. I’ve often thought that if I had stayed married I would have put on weight, all married women put on weight, marriage is a godsend for the scrawny—but marriage absolutely did not interest me anymore, I would have done anything possible to gain weight except remarry. I was married for three weeks in my life, three magnificent, almost intolerable weeks, and then I asked for a divorce and took up archaeology, specializing in utensils. Neither monuments, nor vases, nor coins, nor human remains; just utensils. I became such an expert in the field of utensils that I was called to the four corners of the earth; not a single utensil saw the light of day that did not pass through my hands, or submit to my judgment. To the husband I left after three weeks of marriage, I gave no explanation. He consented to the divorce: for me, he would have consented to anything. His consent saved me from a marriage I would not have been able to bear—that’s how I was made, you see. The love I had for my husband, whose loss I constantly foresaw, only made me suffer, so much so that I had no other alternative but to suddenly end it. Since then, I pushed aside my feelings and had an exclusively cerebral existence. Archaeology filled up my life, archaeology has proved to be fascinating—but archeologists stupefyingly tedious, full of tics and manias, some completely without scruples. The same rivalries that exist everywhere exist among archaeologists—being the first to arrive at a location, the first to dig, that’s what they’re fixated on. We learn much more from utensils than from any other remains, nevertheless archaeologists neglect them to rush over to skeletons and ruins that are most often not of the slightest interest. But I have completely abandoned archaeology at the moment, the archaeology magazines that continue to be sent to my home pile up before I can even glance at them, and when I am asked for a consultation, I claim that I can’t see clearly enough to distinguish a fork from a knife. Earlier, while I was in the elevator with the Englishwoman, the thought occurred to me that she was perhaps disturbed. Maybe the rats only exist in her imagination, I said to myself, and her husband pretends to believe they are real so as not to contradict her; maybe even the hotel manager has been informed of her mental instability, which is why he satisfied her desire to occupy a room in the rugby players’ wing. But the Englishwoman, under the elevator light, seemed to me so charming, so sweet, and so eager to recover as quickly as possible from the trauma, almost apologizing about it, that I rejected the thought she might be unbalanced. Still, it’s bad publicity for the hotel. It’s a fact that rugby players are extremely reassuring, like all athletes. Athletes, especially professional athletes, are excellent company for worriers, because they are devoid of the kind of imagination that breeds worry, and they display an exceptional sangfroid in cases of emergency. Had they been the ones to discover the rats, the rugby players would have taken control of the situation right away—the mere sight of the rats would have provoked their automatic imperative to destroy them, and they would have immediately seized anything that fell under their hands to do it, even if they had to tear out the curtain rods. The rats had the right idea, avoiding the rugby players’ rooms. The Englishman also apparently displayed sangfroid at the sight of the rats, but it had no effect on his wife, his wife evidently preferred a completely different variety of sangfroid, the kind that emanates from rugby players. And now despite the husband’s show of sangfroid, here he is constrained to postpone his wedding night, relegated to the other end of the hallway, separated from his wife by a bunch of rugby players. In truth, the Englishman seemed icy to me at the elevator door, the way he had of seizing his wife’s arm and dragging her toward the dining room. But perhaps upon spotting me he anticipated, correctly, having to have a conversation about the rats, anticipating with dread the curiosity of an old woman and her old-woman-concerns about rats in the hotel, etc. I forget at certain moments how much I’ve aged, just as you’ve aged, you’re a very old man, getting old took so little time, isn’t that right? It’s hard to believe, and now here we are, you and I, in this garden in Portugal, tired but still alive, still capable of appreciating the Portuguese flowers and the Portuguese trees and the extreme comfort of the chaise lounges on our balconies, where our muscles instantly relax, where we never know if we are lying for the last time, the thought occurring that perhaps Detective Bonneau, alerted by the maid, will have to break down the door of our room to discover us dead on our balcony—so that personally I never lock my door, anxious to spare Bonneau this grim task. I know where we stand, you see, from this point forward—we arrived here so quickly, you and I, so far from what we had imagined, although, naturally, we had imagined this too. This morning when I saw you in your pajamas in your room—whether it was your smile or your pajamas, it was like seeing him again, I mean him, my husband, sixty years later—a fleeting thought that I nevertheless had to immediately cast out of my mind. So it’s still there, after all these years, I said to myself. No matter, it is to you that I am speaking tonight, and it is time that connects us to one another, here in the garden, there is nothing left but time for you and me, that’s the way it is. But we should go to dinner now, the dining room will soon close. Tomorrow, according to Detective Bonneau, tomorrow at first light, the exterminators will come.

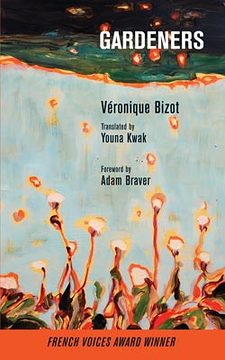

From Gardeners. Used with permission of Lavender Ink. Copyright © 2017 by Véronique Bizot Translated by Youna Kwak.