The Colombian heiress had problems of her own, obviously. Traumas I couldn’t relate to. She was very stressed out from writing her thesis on the economy of Colombia and the way it was affected by riots on the coast, as well as feeling like she was trapped inside all day. Her parents kept strict eyes on her, always worried about her diabetes and her taking the train. There weren’t many accessible stations, so she got everywhere by car. Her assistant, Jorge, came in and asked us what we wanted for lunch.

“The usual, porfis,” she said. I always worried that one day, there would be no lunch, that she would send me home early and starving, but there was always, always lunch: large sandwiches from Cardullo’s, stuffed with prosciutto and cheese and arugula, bathed in olive oil. I’d have one half with the Colombian heiress and then have the other for lunch the next day. I almost can’t look at the photos of myself from back then. I was so skinny. I practically got off on survival, as if living in New York City on my own was like climbing a mountain every day for a chance at sipping water. I feel envious of that previous me, but also concerned for her and the bones stretching against her skin.

That day, we were going over an essay she needed to finish for her comp lit class. I had taken most of the notes for her, and she just needed to write out the paragraphs.

“This is so boring for me,” she said. “Can we take a break?”

“Sure,” I said, closing my used Mac. She took out a baby pink vape and sucked from it like it was a bottle. She offered it to me, and I declined.

“What do you want in this life?” The vape smoke smelled like unicorn farts.

“I don’t know,” I said. “I just take it one day at a time, I guess.” With her, I spoke in American idioms found above fireplaces in summer homes.

“So smart,” she said. “You say the most beautiful things to me.” Her eyes were giant pools. Jorge returned with the sandwiches. I ordered mine with spicy sauce. She did not. I thanked him, and he bowed away.

“Do you have a therapist?” the Colombian heiress asked, biting into her sandwich. We sat by the giant bay windows. I shook my head, blocking my sandwich-filled mouth with my finger. I’d recently had to stop seeing mine because I couldn’t afford the eighty-dollar co-payment. In the years that would follow that day, I would spend a few semesters’ worth of money on therapy, waking up in the middle of the night screaming, breathing in too much air, and taking propranolol to slow my heart rate.

A white van pulled up on the street below us. Spring was coming, and with it, the small sadness that I hadn’t been as productive as I could’ve been in the winter. The alarm on my phone went off. I had forgotten to charge it while I was here.

“All right,” I said, “I gotta bike home.”

“Do you hate me?” Tears brimmed in her eyes.

“What? No, of course not.”

“I am just so bad with these school things. You are so helpful.” She sniffed.

“I don’t hate you. Really. I just have to go now. I have plans.” I didn’t.

“I can have Jorge make us micheladas. We have beer.”

“ Aren’t you gluten-free?” She tsked and flicked her hands at me. Of course she had gluten-free beer. Or just didn’t care about the repercussions.

“Stay with me.” I did. The micheladas were spicy and sweet. Jorge served them to us with a wink. Pushing the cuticles back on her nails, she said, “Sometimes I feel so empty. I want something to happen to me. I thought we were in the big city. Harry meets Sally. I want to fall in love.” She asked me if I was in love, and I told her yes, even though I wasn’t technically in love with Lawrence anymore. He’d texted me a video last month in reference to something I’d once said about pineapple on pizza. I formed a message and didn’t send it because I was so depressed thinking about the ten or so banal messages that would pass between us.

“Thank you for stay with me,” she said. “I needed this. We will do it again.” I pulled my jean jacket over myself. She gasped.

“You need a coat,” she said. “It’s cold. Jorge! She needs a coat!” Jorge came with a pink fur coat held up by his hands.

“You can have,” she said. “Is my gift to you.”

“That’s okay,” I told her. “Plus I’m gonna get it sweaty from biking.”

“Take it. I have too many.”

I stepped out of the apartment building and down the steps, opening my phone to see that it had died, and then—everything went black.

I woke up in the back of a van with a rag in my mouth.

“Is she awake?” I heard them say in Spanish. “Wake up,” they said in English.

“Are you sure this is her?”

“Yes, look at the photo.”

“But I thought she had no legs.”

“She has legs; she just can’t use them.”

“No, she can’t use one of them.”

One of them touched my ankle, and I shook it away. Then the other ankle. I shook it away.

“We got the wrong one.”

“Well, now, what do we do with her?”

“Get rid of her.” They took the rag out of my mouth, and I tried to scream, but all I let out was a little whimper, a tiny clock chiming. One of them wrapped his hand over my mouth.

“Take her,” I heard them say. “And take care of her.” They shoved a pillowcase over my head, and obviously, this was when I thought I was going to die. A hand led me by the wrist as I stepped over rocks. I can still smell it now. I can still feel the saltiness on my skin.

“Are you going to kill me?” I asked, feeling a cold pistol through my T-shirt. The man said nothing. I sighed. I was weirdly calm, which I’ve heard happens at the end of your life. You can’t survive anything if you’re freaking out. “Are you going to kill her?” He was still quiet, but I heard a sniffle. Was he crying?

“You don’t have to,” I said, feeling bad for him but also feeling like I was on the edge of a very tall building. “Nobody knows me. I’m just a tutor. I’m literally moving in a week.” That was a lie. I wouldn’t move for another year, with Lawrence, a few months after we would reconnect, when his mother died. “I could move tomorrow!” Another lie. I felt the gun leave my back. Through the pillowcase, I saw little ideas of light, cars and buildings and e-bikes and boats, all these things that make a city. I felt the pillowcase lift off me. We were facing Brooklyn. I turned slowly and saw a short guy with a shaved head and a yellow handkerchief over his mouth. I could see the muscles forming like packaged produce beneath his white T-shirt.

“Ransom?” I was so unbelievably calm. Later, when I would finally get home, I would throw up in my toilet and fall asleep on the bathroom floor, crying.

“I won’t tell anybody,” I said, looking down at my hands, dry and weathered from biking all winter. He looked toward me. He had deep brown eyes that were a little close together and lived in dark, sleepy sockets. There’s so much I haven’t done, I thought, looking at a squashed water bottle with bits of orange floating around the bottom. Vitamin C mixed up with spit. I waited for panic to come, but it didn’t.

“What if we went on the ferry?” I said, my last resort, my emotions blunted by a need to live. A train passed below us. I knew exactly how to bike home from here. Maybe I could run. But that didn’t mean I wasn’t in danger. He made a move with the gun and I flinched, but he was just opening my backpack, which was once pink and had now turned a scabbed-knee color from my sweat. He placed the gun in the backpack and threw the backpack over his shoulder. His eyes darted to me. He was just a kid, I realized.

“So, yes?” He was clutching onto the straps of my backpack, which held the gun that could’ve blasted a bullet through my skull. He gave me the slightest nod. Really, it was more of a twitch, but the twitch showed me that I was in charge now. A few worries pulsed through me: Would he rape and kill me if he felt like I was leading him on, was I being xenophobic thinking that, was I being naïve not thinking that, was it self-centered to think someone was going to rape me, why had he suddenly changed his mind? I was young, but I wasn’t an idiot. I was just trying to survive.

“Okay,” I said, “well, come with me.”

It wasn’t weird for him to be wearing a face covering because of the times, so I fastened mine on as well. We just looked like two people walking into an establishment politely. I bought us two tall Modelos and made a joke about how he should technically be buying because this was a first date, but he didn’t laugh at that. I talked to him in jilted Spanish that had been improving from my time with the heiress. Not because we spoke it to each other, but because her intonations had bled into mine. I could be singsongy, have a personality. In the light of the deli, I noticed his forehead and the lack of wrinkles around it. I guessed he was Central American, just because of his height. I thought about all the things that had collectively brought us together: our mothers sweating on hospital cots, after noons spent watching teen stars make the Disney sign with green lightsabers, the way travel was forever changed after 9/11, recessions, adult cartoons. But I wanted everything to have meaning back then. He probably hadn’t had cable.

We walked to the docks, looking like tourist siblings. Like we had both just arrived and were trying to see what it was all about. I tried to make more small talk with him, but he refused, so I eventually gave up and decided that our legs walking slowly in time was conversation. We had a silent agreement. We were both just really bad at our jobs. I always advocated for that, even now with my students. There’s no reason to give your all to your nine-to-five. We walked to the waiting area and waited to be shuttled like everybody else onto the boat. I thought about running to someone who looked trustworthy and grabbing them by the arm and telling them everything: I’ve been kidnapped! But I started to trust him then. I still can’t say why.

I was freezing, even with the heiress’s coat. I handed him a Modelo, which he cracked open with a square thumb. There was a valley of veins moving over his hands, blue rivers poking underneath his hairless arms. I looked away when he lifted his scarf, which I felt him ask of me even though he hadn’t opened his mouth.

“I feel like she actually would have loved all this,” I said finally, breaking our contract. I sipped my beer. “She never gets out of that apartment, you know.” He nodded, and I still didn’t want to look at him. I could smell his sweat. It was the nervous kind, because of the consequences or because he was close to me. Some tourists were huddled in a small mass against the fence, taking photos of the Statue of Liberty. In a few years’ time, I would go to Paris with a lover, one I’d meet at a farmers’ market, overlapping my time with Lawrence. It would be dramatic and cause an entire friend group to never speak to me again. But we would go to Paris together and take the boat ride on the canal that takes you through the city. There I’d learn that the Eiffel Tower was built in two years and how, because of that, it needs to be repaired every six years, and the repairment itself always takes three. So many people get paid just to keep myths alive. The Farmers’ Market Guy and I would end things because he couldn’t deal with my PTSD.

I looked toward my kidnapper, who had taken out his Android to snap a photo of the Statue of Liberty. Lighting up bits of the water, with the city twinkling behind her like millions of eyes, the statue was breathtaking. A teenager next to us held up a Bluetooth speaker blasting a New Order song. The air that was almost spring blew my hair back. How else can I tell you what I felt then? That the feeling, every so often, runs back to me like a dead family dog whenever I hear that song, whenever there’s a body of water, whenever there’s beer. I was alive, and that’s all.

He pocketed his phone, looked at me, and shrugged. I laughed. I still wondered if I would die. If I would say, But remember our moment? as he pressed the gun to my temple. If I, with urine running down my leg, would plead, one last time, Remember your phone and the statue and the teenager with the Bluetooth? The ferry reached Staten Island too soon, and we both slowly made our way off. I was a little buzzed.

“Now we just go around and then back.” I was excited to show him how simple it all was, how we could do it all over again if we wanted, going around like a record. It was a well-known hack. Something that was free, until they decided to take it away from us. We walked through the station, he and I, and stopped briefly at the gift store, and I thought of the Colombian heiress, looking for her name on the key chains but only finding mine. I couldn’t buy anything. My wallet was in the backpack with the gun. He stood at the edge of the store, hands behind his back, like some kind of dad.

The call for the ferry came, and we sat inside this time. He cradled the backpack between his legs and dropped his head in his hands. I figured that if I was about to die, I might as well touch somebody, without force and full of intention and meaning. I remembered how Lawrence had a thing about elbows. How, when we would fuck, he’d pull my arms back and hold on to my elbows, not even looking at my face, just kissing them and nibbling on them a little bit. It really got him going. It also made me think about how underrated they are: pointy and fleshy, funny and there. I held on to my kidnapper’s elbow like it was a handful of fruit or a doorknob, and he didn’t shake me away or hold my elbow back. It was eighteen minutes of unconditional, one-way elbow holding, and I would keep doing this throughout my life, holding on to elbows when it mattered: Lawrence’s again the night we got back together, my friend’s during her last round of chemo, my mother’s when I finally returned to the beautiful home I had run away from, the Farmers’ Market lover’s, my now ex-husband’s, my son’s.

The ferry pulled back into the Manhattan station. I told the kidnapper I had to pee. He waited by the entrance of the bathroom with my scab-colored backpack, and I held up two fingers. In the bathroom, I pissed out my beer, pulled up my cutoffs, tucked in my cotton T-shirt, and slipped on the heiress’s coat again. I washed my hands and looked at myself in the mirror, pulled my hair back, then let it down again. I made faces in the mirror as if I were talking to him, seeing how I had looked, how I had behaved. When I opened the door, my backpack was on the floor, and he was gone.

I took the 4 and switched to the J at Fulton, looking around me and seeing only a police officer on his phone.

“Excuse me?” I said, trying to fill my mouth with saliva. He peered up at me, and I realized I didn’t know what I would say. Would I change the color of the handkerchief of the kidnapper because I wanted to protect him? Had they already gone back for the Colombian heiress? Was it already too late? Would he come back for me?

“Ma’am?”

“Is this the right way to go downtown?” He pointed to a sign and grunted, then returned to his phone. On the train, I kept thinking I saw the kidnapper in every flash of yellow. When I got home and charged my phone, I messaged the Colombian heiress on WhatsApp.

Hey, are you okay?

Yes, she responded, too quickly. Why?

Nothing. Stay safe out there.

Gracias :] I loved the micheladas today!!!! I fell asleep and dreamed of lights behind cloth. I skipped my classes that week and saw nobody. I worked on some writing, but everything was too long and rambled, like I didn’t really know what I wanted to say.

Finally, the following Thursday, I arrived at the Colombian heiress’s apartment. Jorge opened the door. He told me she had left a week ago, and he could not tell me where, for security reasons.

I was sweating beneath my jean jacket. “If you hear from her,” I asked him, “can you tell her to text me?” I didn’t want to admit that I wished I could’ve said goodbye—and I still do, because I never saw her again. Her presence on socials was blank; a few fake ones popped up and then vanished. There was nothing reported on the news. When I called the embassy, they were tight-lipped, then asked me why I was so concerned.

“I will,” Jorge said, and I swear to God, he winked at me, and then he closed the door.

I walked to where I had locked my bike, on some scaffolding on Sixth Avenue, fully expecting it to be gone and calculating how much I would have to put aside to buy a new one. But my bike was still there, the one I’d bought used a few years before, with the basket an ex of mine had lovingly screwed on. In six years, it would get lost to a flood in my building. I’d have to find a new job, of course. I’d have to go back to the tutoring agency to see if they could place me with somebody else. One way of making a living leads to another, until something evil with health insurance sticks, like a start-up or a finance bro who is willing to marry you. That’s what I used to think, anyway. About all of it.

I am so far into the future now, but I still feel like I am there. Or maybe I can just see her so clearly: this skinny girl unlocking her bike. I love her, checking her breaks, squeezing the wheels, patting rainwater off her seat, turning the pedals with her finger, clipping her helmet over her head, mounting the bike swiftly. What a silly girl, what a way of life. She pedals up the Williamsburg Bridge and races the J as it buzzes by, ass up, thighs strong. The train is always faster than her, but it’s fun, for a moment, to believe. The road’s treacherous and full of cement trucks and e-bike deliverymen, people in SUVs who can’t see her and don’t give a damn, ass holes just trying to get where they need to go. She rides past white bikes chained to fences decorated with flowers, thinking, That could be me. She has seven hundred proud dollars to her name. She has a single KIND bar rattling around in her backpack. She has time.

__________________________________

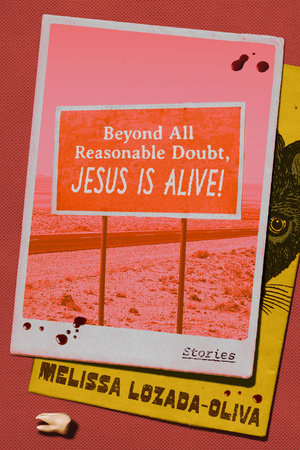

From Beyond All Reasonable Doubt, Jesus is Alive! by Melissa Lozada-Oliva. Published by Astra House. Copyright © Melissa Lozada-Oliva 2025. All rights reserved.