The Haunting of Alice B. Toklas

Seattle’s Smartest Writer Holds a Literary Seance

Like many of the greatest moments of Seattle’s recent APRIL Festival, the literary séance came about due to a happy accident. APRIL—it stands for Authors, Publishers, and Readers of Independent Literature—features a popular annual storytelling competition pitting a poet, a playwright, a novelist, and a drag queen in narrative combat. At last year’s competition, the damned wireless mic wasn’t working; the audience in the Sorrento Hotel’s stately Fireside Room started to murmur and a nervous twitching rippled around the crowd. As increasingly panicked APRIL staffers tried to batter some sense out of the hotel’s ancient wiring, an enterprising waiter took the stage and gathered up the crowd’s attention with a single sentence: “Did you know the ghost of Alice B. Toklas haunts the hotel?”

That had them. The waiter knew his audience: he didn’t just tease them with your standard white-sheeted apparition or blood-gushing elevator. He won their rapt attention by invoking the spirit of Toklas, Gertrude Stein’s lifelong lover and muse. Supposedly, he explained, Toklas was spotted on multiple occasions in room 408 and in the fourth-floor hallway, wearing a flowing white gown. She never talked, she never touched anyone, she just walked around like she owned the place, and then she’d disappear.

Eventually, the mic popped back to life and the show went on. (For the record, the playwright won.) But the ghost story continued to circulate. When Seattle-area author and celebrated Stein fan Rebecca Brown heard about it, she had “a conniption,” says APRIL co-founder Willie Fitzgerald. Brown approached the APRIL organizers with what Fitzgerald describes as “a small biography of Toklas” that she had written for research, and she proposed the idea of a séance.

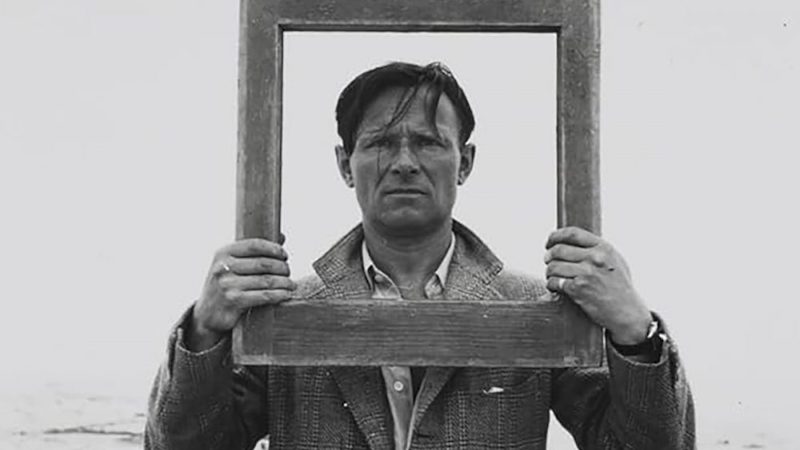

When Rebecca Brown comes to you with an idea, you say yes. Because the question is not whether Rebecca Brown is the smartest writer in Seattle. The question is whether Rebecca Brown is the smartest human in Seattle. Brown is the author of a shelf’s worth of brilliant books including the novel The Gifts of the Body, the short story collection The End of Youth, the memoir Excerpts from a Family Medical Dictionary, and the essay collection American Romances. In Seattle she has earned a reputation as a legitimizing force. If Brown, with her solemn devotion to the written word and her sly, devastating sense of humor, agrees to be a part of your reading, you must be doing something worth the effort.

This makes her sound like something terrifying and distant, but the truth is that Brown is a generous teacher and a warm, caring member of the community. She helped launch the second year of APRIL with a remarkable convocation (Brown is a practicing Catholic) invoking the frivolity and importance of writing that has acted as a mission statement for the festival ever since. Her intellect, though, her wizardry with words, is intimidating as hell. Who else could write an essay about transubstantiation and Oreo cookies that forces its readers to reconsider their relationship to faith?

Fitzgerald and APRIL co-founder Tara Atkinson immediately took Brown up on her offer; a séance is a perfect fit for the small, literary-minded festival. In a city as willfully agnostic as Seattle, the concept of toying with spirituality claimed a certain lo-fi whimsy that appealed to the organizers.

APRIL’s events are typically site-specific, they thread multiple disciplines through the traditional structure of a reading, and they demonstrate a special blend of drama and play. Like the best APRIL events—the literary pub crawl where Atkinson read a story about fast food and loss while being pulled from bar to bar in a red wagon down rain-glistening sidewalks; the brutal, bleak poetry reading by Matthew Rohrer, Heather Christle and Rauan Klassnik that ended with a surprise fried chicken feast—the idea of a séance had that particular sublime-humps-the-ridiculous appeal that Atkinson and Fitzgerald preferred in their events. Brown pitched it as something silly and serious and obsessed with death, but only in a funny way. APRIL couldn’t argue with that.

So it’s been a year since a waiter saved an imperiled reading from a technical difficulty with an impromptu spooky story about a wayward literary lover, and now here we are in the same room waiting to say hello to Alice B. Toklas, with Rebecca Brown making the introductions. In front of a fireplace is a lumpen table covered with scarves. Surrounding that table are the evening’s readers. Surrounding the readers, sipping from fancy cocktails and eating french fries out of small silver bowls, are dozens of Seattleites who all apparently spontaneously decided to buck Northwest casual-dress tradition for fancy clothing—the men are wearing jackets, a few women are wearing evening gowns. They look resplendent, sitting in their comfortable wingback chairs and sofas. Everyone is playing with the black-and-white Gertrude Stein masks organizers placed in every plush seat in the Fireside Room, the face a spray of angular lines and the eyes full of crackling static. Fitzgerald says a few words of welcome—“tip your waiters; this is a weird room”—and Atkinson reads Toklas’s famous recipe for marijuana brownies (“two pieces are quite sufficient”) as APRIL staffers circulate heaping silver trays of (non-pot) brownies made from the recipe, and then we are ready to raise the dead.

* * * *

In the first of what will be a series of brief, informal chats, Brown lays out the whole of Toklas’s life. Born in San Francisco in 1877, Toklas moved to Seattle’s First Hill neighborhood for two years when she was twelve. Shortly after leaving Seattle, her mother died of cancer. “The happiest years of her life were here,” Brown says, “so why not haunt here?”

Brown jumps ahead to Toklas’s arrival in Paris, and what the introduction of Gertrude Stein did to her relatively safe and normal life. When Stein walked onto the stage of Toklas’s consciousness, Brown says, “I’m not going to say lesbian drama ensued, but lesbian drama ensued.” She reads from Toklas’s actual autobiography—confusingly, not Stein’s The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, but rather a book titled What Is Remembered which Toklas published years after Stein’s death. From the night she met her, Toklas says in Brown’s voice, “it was Gertrude Stein who would hold all my attention.” Toklas’s awe is evident the next day, when she was late to meet Stein for their second informal ‘date’: “She was now a vengeful goddess and I was afraid.” Soon enough, though, they were out for a walk together and falling in love: “They walked and walked and walked,” Brown says. “Later in life, they got to walk with a dog.” Brown urges the audience to hold their Stein masks in front of their faces and ask for Alice. Some light chanting ensues. “That doesn’t seem to have worked,” she says when no spirit appears.

Poet Joshua Beckman reads all the Toklas-related passages from Stein’s memoir Wars I Have Seen. The longest passage is about Alice Toklas wanting a cigarette. It ends “…and Alice Toklas was happy again.” Beckman notes that Stein refers to Toklas as “Alice Toklas,” with the full name like that every time, and that Toklas referred to Stein as “Gertrude Stein” in a silly flourish of respectful formality.

Brown asks the audience to don their Stein masks and summon Toklas again, this time encouraging half the audience to call for Alice and the other half to ask for “Mama Woojums,” Stein’s pet name for Toklas. (Toklas called Stein “Baby Woojums,” and Brown says “I’m not going to go into the infantilism that suggests.” She admits that Stein “was a little creepy,” but she wonders who among us wouldn’t be creepy if our lives were submitted to public inspection the way Stein and Toklas’s lives have been. After all, who are we to call anyone creepy as we collectively wear a dead woman’s face and call for her lover’s ghost using secret terms of affection?) Brown makes like an orchestra conductor, directing the left side and the right side of the room in dueling chants of the public and private names of Alice Toklas. No specter arrives, and so it is time to break out the Big Spiritual Guns.

Brown’s friend Jan Wallace is a local poet who reads tarot cards for a living. She explains that she didn’t believe tarot was a powerful enough divination for the evening, so she decided to “take a crystal ball and do a full-on séance.” Wallace pulls the scarves from the table in the center of the room, revealing a spray of white candles and a large crystal ball. The audience ooooohhs and giggles appreciatively. She did research into how to do a séance, Wallace says. “On WikiHow it’s a nine-step procedure, but I don’t have time for that so I’ll just do three.”

“In traditional séances, we hold hands,” Wallace says. “I feel that this is Seattle and we should not do that.” The room, recognizing their very Seattle-y nervousness about strangers violating their personal space, breaks into laughter. “Just clasp your own hands,” Wallace reassures us, and leads us in a chant:

“Mama Woojums, Baby Woojums, Cow cow cow.” (“Cow,” she explains after the chant is done, “was a secret word they used for a very private time.”) When nothing happens, Wallace drily remarks that her best efforts have gone unrewarded.

It’s about the time when Brown takes the stage again that I realize this whole ceremony has been an echo of a Catholic mass, with a communal sharing of “bread” taken from the body of Toklas’s work and two readings followed by responsorial psalms. This means that Brown is preparing to deliver her version of the gospel.

“Ignatius was Stein’s favorite saint and I don’t know what that means,” Brown says. She talks about the way that Toklas, an agnostic, embraced religion at the end of her life, and while she doesn’t presume to know Toklas’s inner voice, Brown says she could understand “wanting to know and to believe in heaven so she could be with her beloved” in the afterlife. And now here we are, making a joyful pass at a séance because we want her to be with us. “What it is to be haunted is to remember,” she says. The tuxedo jacket she’s wearing, Brown confesses, belonged to her father, who died many years ago. “Is a jacket haunted? Is a hotel haunted?”

Finally Brown, who has spent the whole evening bobbing her head in time with Beckman and Wallace’s reading of Stein’s words the way you move your body in time with the music of your favorite band, admits that we can know nothing for sure of Toklas’s experience, that we’ll always be haunted by the thought of her. Though we have an astounding body of first-person narrative from Toklas and Stein’s 30-plus year relationship and a small library’s worth of writing about their time on earth, we can’t really know much for certain, except that “Gertrude Stein did make Alice Toklas very happy.”

Brown is joined onstage by a bearded Stein impersonator. He’s carrying a chihuahua named Bruce who’s dressed in poodle drag—he’s a stand-in for Basket, Stein and Toklas’s beloved poodle. Together, Brown and the faux-Stein and faux-Basket make a last-ditch effort to summon Alice with a Ouija board.

Brown asks, “Alice? Are you there?”

The stylus moves across the board: Y-E-S

“Hello, Alice,” Brown says.

H-I

“Alice, what do you have to say?”

I-L-O-V-E-G-E-R-T-R-U-D-E

“Alice, is there anything else?”

G-O-O-D-N-I-G-H-T

And then Brown stands at the end of the stage waving out into the Fireside Room, shouting “goodnight, Alice!” And it’s such a goddamned sweet moment, like Peter Pan urging the kids watching TV at home to clap their hands to will Tinkerbell back to life. Brown is joined by the Stein impersonator and the imaginary poodle, and the readers, and the APRIL organizers as the room fills with applause, and they all pose for photographs with Toklas, their arms stuck out hugging spectral shoulders with huge, genuine grins plastered on their faces. The hotel fills with goofy smiles, and as people turn to each other to ask what they thought of it all, nobody describes the evening the same way as anyone else; was it a reading? A biographical sketch? A religious ceremony? A complex thesis on the troubling relationship between writers and readers? A meditation on the relationship between an artist and her muse? A love story? An elaborate work of fan fiction by one of Seattle’s most brilliant writers? Yes. It was all those things. And wasn’t it just great?

(Image courtesy of APRIL)