The Hate Mail I Got When I Wrote About My Hometown in Upstate New York

Brock Clarke On Capturing the Messy, Individual Voices of Little Falls

I’m from Little Falls, New York, a tiny city (The Only City in Herkimer County! says a t-shirt I’m wearing as I type these words) at the confluence of the Erie Canal and the Mohawk River, not far south of the Adirondack Park. Growing up, I thought Little Falls meant nothing to me, but once I started writing fiction seriously in my mid-twenties, I discovered that it meant everything to me. That I couldn’t live without it. That I loved it.

You’d think, then, I’d have no problem declaring my love for it in print, or in public. Except that whenever I talk about, or write about Little Falls and upstate New York (I’ve written about Little Falls, about Utica, about Rochester, about Watertown, about a fictional place called Broomeville that is in approximately the same place as, but shouldn’t be confused with, Boonville), whenever I try to show my genuine love and affection for those places in print, I end up making a lot of people who live in those places hate me.

Take, for example, the response to an essay I wrote for the New York Times a couple of years ago. It’s called “Do it For Utica!” and in it I facetiously suggest that the Danes move to upstate New York, or that upstate New Yorkers move to Denmark, as a way to solve our mutual under-population problems. I thought it was a fond, gentle satire, in which I show my affection for both places by poking fun at them, and at myself. But apparently I was wrong in thinking that, at least according to this email:

Greetings,

You must realize sir that you cannot go about being an asshole all your life. I saw the article about Utica. May I ask, with all respect, who the fuck do you think you are? Have you even ever been here? Well, Let me state that after reading this my next communications are with the paper you wrote for, and it will be very specific on the issue of fuckheads like you sir allowed to have a computer to be an asshole. I was born and raised here, it is not the biggest or best city but—it also is nothing like the shit hole you live in inundated with fags, drug dealers, and hookers. Pollution and probably every non-caring ass wipe that lives in there! In closing—Go fuck your self!

Allan

After getting several emails just like that one, you’d be leery of talking about how much you love a place, too.

Except that the email suggests exactly why I love the place, as a writer, although not always a person, because there’s sometimes a big difference between being a writer and a person. For instance, there are two ways in which I love Little Falls. One, I love it as a person who is connected to the place. I grew up there, with my brothers, whom I love, and with my parents, whom I love and who still live here, in a pretty house with a beautiful view of a beautiful place. I have friends here and my parents have friends here and they all mean a lot to me, and now that I have a kids we come back here to visit and they love the people and the place, too. In other words, I love this place, as a person, for the reasons lots of people love lots of places: because it is full of good people, because it is beautiful, because it is an interesting place, full of hardships, but also full of hope, and heart.

You know you’re not doing your job as a writer when what you feel and write about a place would do well as a slogan on a state license plate.

It is also not a boring place—in some ways, this is the most exhilarating place in which I’ve ever lived—but while my description of why I love it is sincere, it’s also boring. It’s boring because it’s generic. As far as my description would let you know, upstate New York is worth loving because of its smiling faces and beautiful places. Smiling faces, beautiful places, my friends, is also the slogan on the South Carolina state license plate. You know you’re not doing your job as a writer when what you feel and write about a place would do well as a slogan on a state license plate.

Allan, my friend from Utica, his words would not do well as a slogan on a state license plate. That is why, as a writer, I love him. Or at least, find him useful. And for a fiction writer, or at least this one, utility is often synonymous with love.

His voice, for instance. All fiction—at least, all of my fiction—relies upon voice, a distinctive voice. Allan’s is a distinctive voice, a voice that has range, a voice that wants to be formal (he begins his email with “Greetings, and he calls me “sir,” both of which I appreciate), but also loves to be profane (he asks who the fuck do I think I am, which is a fair question). This is a very literary voice and also a very regional voice (there are voices exactly like this in novels by Watertown’s Frederick Exley, Gloversville’s Richard Russo, and Albany’s William Kennedy), a voice that really wants to sound high, but is most impressive when it sounds low. A voice that is accidentally eloquent (which to me is the best kind of eloquence). In other words, a voice that struggles.

The writer Donald Barthleme once said that he’d rather have a wreck than a ship that sails, because things attach themselves to wrecks. Allan’s voice is a wreck; that is one of the reasons I’m so attached to it, and why I think there’s so much for a writer to learn from it—namely, the literary virtues of anger, of self-deprecation, of being an outsider, of being from the provinces, and of being unreasonable. I especially love Allan’s assumption that I am from New York City simply because the newspaper that published me was from New York City, even though the essay made clear I was not from New York City. (In fact, the closest I’ve ever lived to New York City was when I lived in Little Falls. Allan’s assumption is exactly one my characters would make, and maybe I would, too.)

These qualities don’t necessarily make a reliable voice, but they do make an entertaining voice, a galvanizing voice, a voice you listen to, even when the voice is hateful. Because I don’t want to underplay that hatefulness, especially the moment when Allan says where I live is a “shithole inundated with fags.” First, I want to point out again this combination of high and low (an inundated shithole is my kind of shithole).

Second, this is what I mean when I love Allan as a writer: I would not want him to be in my family, or in my chamber of commerce, or in my White House (and this is why his hatefulness is significant to a writer: because when he uses the word “fag” he’s not so easy to laugh at anymore. Which then connects him to our larger hatefulness, and makes him bigger, more representative, more serious then most of us would want him to be), but I might want to read a book that has him it. Because who knows what he’d say next, and how he’d say it? Who knows how a writer might use him? Who knows how he might surprise us, and maybe even himself?

You do not, as a writer, show your love for a place for making it generic, for making it just like every place, for making it seem like it’s perfect, because when things are perfect they are boring, and then they’re not worth loving, or hating.

I’m not saying Allan’s is the only kind of voice in upstate New York. I’m not saying it’s representative of upstate New York voices. I’m not even saying his the only kind of voice in my own books. But it’s the one that speaks to me the most clearly, it’s the one that inspires me, it’s the one that helps me animate the otherwise generic ways I’d fall back on to express my debt to the place.

You do not, as a writer, show your love for a place for making it generic, for making it just like every place, for making it seem like it’s perfect, because when things are perfect they are boring, and then they’re not worth loving, or hating.

________________________________________

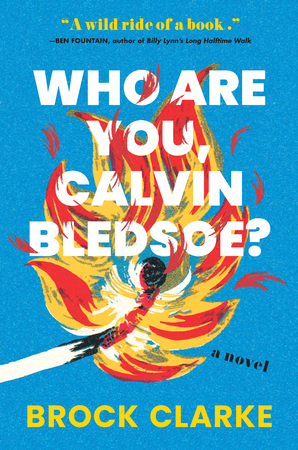

Brock Clarke’s Who Are You, Calvin Bledsoe? comes out on August 27th from Algonquin.

Brock Clarke

Brock Clarke is the author of seven works of fiction, including the bestselling An Arsonist's Guide to Writers' Homes in New England, as well as the essay collection I, Grape; or The Case for Fiction. He lives in Maine and teaches at Bowdoin College.