The Hard Art of Teaching Your Child Where You Come From

Nick Flynn Returns to the South Shore

Five perfectly round stones, each about the size of an ostrich egg, sit on my desk in Brooklyn. My daughter (then seven) had gathered them up from Peggotty Beach on the last trip we took back to my hometown. The beach is just off Third Cliff, down from the last house I lived in as a child. Back then I thought peggotty meant “rocky.” Now each stone sits on my desk like an egg in a bird museum, a diorama showing how all eggs are different—some larger, some smaller, some speckled, some not. Each is dry now, all versions of gray. If I touch my tongue anywhere on any one of them it will come alive.

I was born in the same place as these rocks, in a town formed by glacier. Ten thousand years ago the sun went away—maybe it was volcanic ash, maybe a meteorite, maybe God told Noah to build a boat, told him, I’m about to kill everyone. Now we call it the last ice age. The glacier could push only so far south, then it stopped—maybe the water was too warm, or too salty, for it to go on. When the ice receded, all the earth it had ground into sand was left, and this sand became home to a native people known as Wampanoag (“People of the Dawn”).

Then, after the Mayflower came, full of war and disease and fringy religion, it was christened Scituate, Massachusetts—my hometown. 02066. From that day on, everyone born in that town has ice in their veins. I was born there, beside the Atlantic, in the shadow of that glacier, and now I don’t seem able to escape it. The sound of it. The salt. I need it on my skin. I need to smell it. My mother carried me through the streets of that town inside her. Outside was chaos—lots of drinking, lots of mayhem. Some of this mayhem seeped in, how could it not? When I was born, I came out wrong—two collapsed lungs, staph infection: sickly. For the first two weeks I lived under glass in an incubator, a box like a tiny greenhouse, as if I were a tomato.

Now my job as a father (or one of them) is to tell my daughter stories from when I was her age. Then to bring her back, to show her the source of those stories. So one day she will understand where she is from, what made her. This is the house I lived in when I was your age, this is the saltmarsh I wandered to get to school each day. This is Maria’s, where I got my sub the nights my mother was working late. We go to the supermarket and we each buy a donut, hot out of the oil. The enormous mixer my mother used is still there. I’m trying to make it easy for my daughter, something my mother never did for me, though she did a lot.

I sometimes worry we will not be able to leave. I sometimes worry I never have.

Strange, but I have no idea, still, which house my mother grew up in, and only a vague idea of her hometown, what it was like. Canton is only a few miles from Scituate, maybe half an hour’s drive, and even though my mother and I would often drive, especially on the weekend—aimlessly, wandering—we never drove to Canton. She never pointed and said, There, that’s the house I grew up in. She rarely, if ever, told me stories of her childhood. It seemed she wanted to get as far away from it as possible, as if we were driving through a dream, or away from a nightmare.

My daughter never met my mother, though she’s seen the photos. When she asks how she died I tell her she had a bad heart. This is both a lie and not a lie. When I was having a hard time, I told her it was because I missed my mother, that it was near the anniversary of her death, that I was sad she was gone. This too was both a lie and not a lie. I was thinking of leaving my wife, or, more specifically, I was both thinking and not thinking. This was my chaos. It felt right because I was in control of it. She would have loved to have met you, I tell my daughter, which is true, I guess, but how can I know?

The stones on my desk were gathered from the southern edge of Peggotty Beach, where the breakwater meets the sand, where Third Cliff begins to rise from the ocean. Now, when I bring my daughter here, once a year or so, she spends the day carrying stone after stone to our car. She fills our trunk with so many stones that our tires begin to sink into the sand. I sometimes worry we will not be able to leave. I sometimes worry I never have. The day my mother died she walked down to this very spot. This is the closest water to what was our door, though it seemed the ocean was everywhere. She’d already taken her pills, already begun her note. Unlike Virginia Woolf, she didn’t fill her pockets with stones, so I imagine her body simply floating on the surface, like a witch—that she could float would prove it.

__________________________________

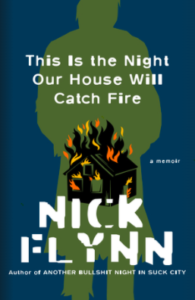

From This is the Night Our House Will Catch Fire © Nick Flynn, 2020. First published by W. W. Norton & Company.

Nick Flynn

Nick Flynn has worked as a ship’s captain, an electrician, and a caseworker for homeless adults. Some of the venues his poems, essays, and nonfiction have appeared in include the New Yorker, the Nation, the Paris Review, the New York Times Book Review, and NPR’s This American Life. His writing has won awards from the Guggenheim Foundation, the Library of Congress, PEN, and the Fine Arts Work Center, among other organizations. His newest book, Stay, is out from ZE Books.