The Groundbreaking Political Legacy of Theodore Roosevelt

David S. Brown on Roosevelt’s Popularity, Charisma, and Progressive Politics

American presidents occasionally perform roles that extend well beyond the formal obligations of their office. Thomas Jefferson’s tenure (1801–1809) embodied the broader progress of antebellum southern agrarian power, while Abraham Lincoln’s term (1861–1865) anticipated the growth of postbellum northern industrial might. More than engaging in tussles over elections, budgets, and boss fights, these men, the former a quasi-aristocratic slaveholder, the latter a largely self-educated model of midwestern social mobility, typified the dominant if transitory directions of nineteenth-century American development. Jefferson’s states’ rights vision collapsed in the Civil War, while a dawning age of corporate monopolization mocked Lincoln’s quaint “free soil, free labor” convictions.

In their wake, Theodore Roosevelt, a conservative drawn to progressive ends, captured the imaginations of Americans caught in the anxieties of the modern—urbanized, industrialized, imperialized—quandary. Many of his achievements as a reformer were partial and incomplete, though he retained a remarkable hold on public opinion. With 56.4 percent of the popular vote in the 1904 election, he claimed the highest percentage in a contested presidential race since 1816 when James Monroe, the last chief executive to wear knee breeches, won over a largely Atlantic-facing electorate.

In contrast to the sectional complexions of Jefferson’s and Lincoln’s respective constituencies, “TR’s great political strength,” so his cousin Nicholas Roosevelt once observed, “lay in his millions of devoted followers, especially in rural and small town America. In a sense he was the first truly national political hero.”

The power of Roosevelt’s popularity stemmed, ironically, from a raft of contradictions.

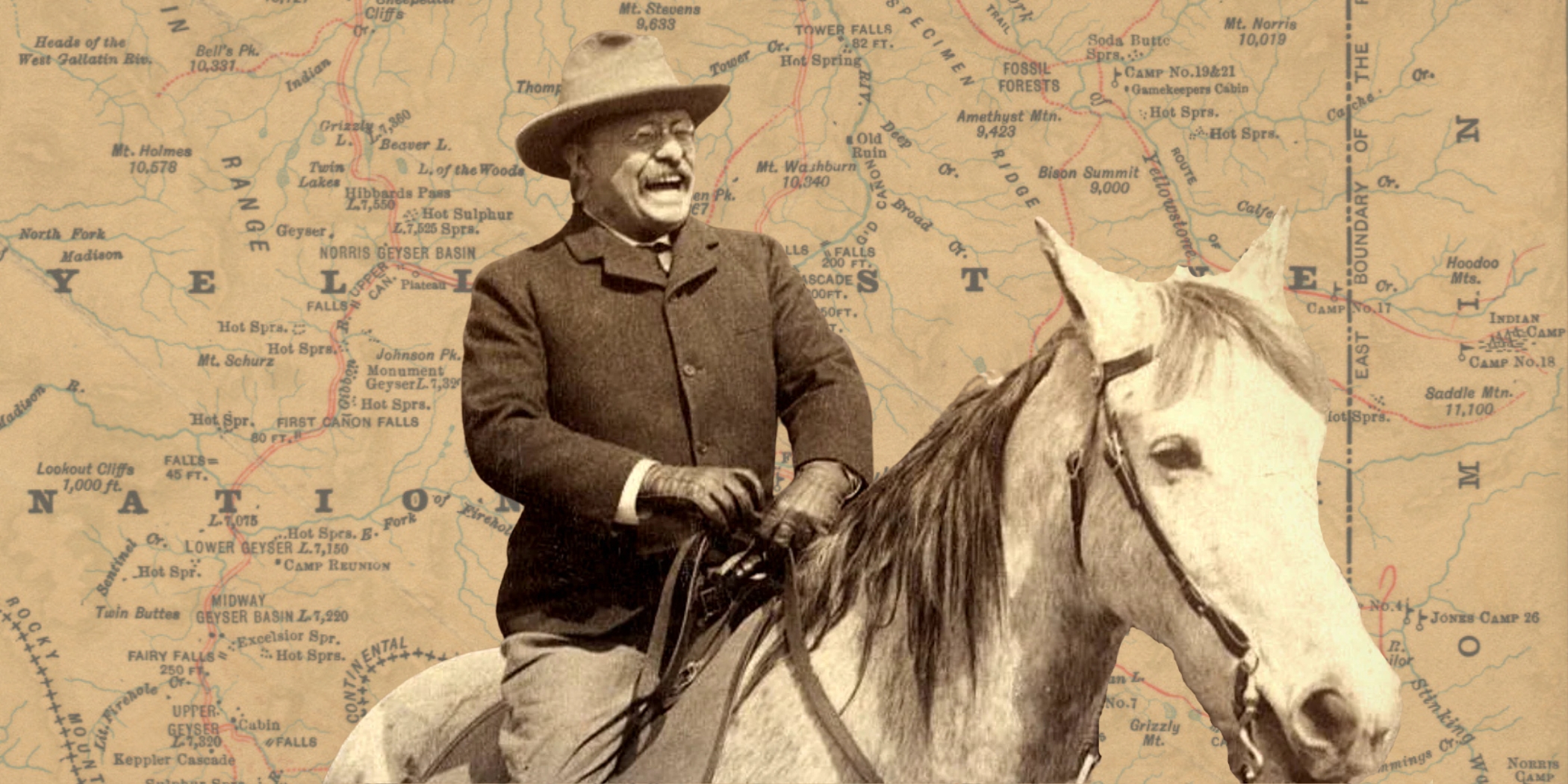

The power of Roosevelt’s popularity stemmed, ironically, from a raft of contradictions. Though a silver spooned Manhattan dandy born into a wealthy merchant and banking family, he lived for extended periods after college (Harvard, naturally) on a cattle ranch in the Dakota Territory, became an unlikely military hero in the Spanish-American War, and, despite endorsing martial glory as a “strenuous life” antidote to the “ignoble ease” offered by a highly commercialized civilization, was the first American to receive the Nobel Peace Prize.

Above all, he represented to numerous constituencies concerned with an economy dominated by factory owners and financiers the dreamy promise of a pre-capitalist hero—hunter, warrior, explorer—who might yet infuse the country with an updated iteration of the old frontier ideals.

Domestically, Roosevelt’s progressive reforms—breaking up dozens of monopolies, modifying railroad rates, setting aside public lands for conservation—cut against the long run of industrial oligarchy enjoyed by assorted oil, timber, and coal kings in collusion with their congressional retainers.

“We demand,” TR barked, “that big business give the people a square deal”; this Square Deal liberalism served as a corrective to classical (unregulated, let-the-buyer-beware) liberalism, thus anticipating a cluster of future government public assistance programs, including Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal, Harry Truman’s Fair Deal, and Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society. By turns loathed and distrusted by any number of plutocrats—“We bought the son of a bitch,” complained the disgruntled steel tycoon Henry Clay Frick, “and then he didn’t stay bought”—Theodore Roosevelt was the first president to attack the problem of industrial fiat.

In foreign affairs, TR presided over America’s emergence as a global power. Leading a volunteer cavalry unit up Kettle Hill in Cuba, he earned his spurs in a war against a fading Spain that brought the island, an “empire of sugar,” into the expanding U.S. sphere; as president he oversaw the conquest of the Philippine Republic, a struggle that foreshadowed the United States’ hit-or-miss entry into future conflicts in Asia against Japan, North Korea, and North Vietnam.

Theodore Roosevelt is among our most relentlessly caricatured public figures.

Schooled in social Darwinism, Roosevelt wielded a big stick diplomacy in the Western Hemisphere that betrayed a barely concealed disdain for Latin peoples not atypical for its time. His great achievement in this corner of the world—construction of the Panama Canal—is inescapably paired with the controversial Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, by which TR announced America’s right to monitor the internal affairs of the Caribbean countries in the manner, so he told Congress, “of an international police power.”

The groundwork was thus laid for a series of interventions and occupations, often by the Marine Corps, and usually to do with securing U.S. dominance over tropical trade in Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Honduras, Mexico, Panama, and elsewhere. Reflecting on these so-called Banana Wars, the Nicaraguan-born poet Rubén Darío offered a defiant 1904 ode “To Roosevelt”:

You are the United States,

You are the future invader . . .

You think life is fire,

That progress is eruption;

Where you put your bullet

You put the future.

Roosevelt’s strong domestic program and personalized foreign policy—he said, of severing Panama from Colombia to forward the canal project, “the vital work . . . was done by me without the aid or advice of anyone”—helped ignite a contentious competition between the branches of government. For many years Capitol Hill had claimed rank. But TR proved to be the nation’s strongest peacetime president since the notoriously combative Andrew Jackson, who had vetoed more bills than all his predecessors combined.

In Old Hickory’s long shadow a series of failed 1850s administrations, followed by Lincoln’s assassination and the near impeachment of Andrew Johnson, reinforced the course of congressional preeminence until Roosevelt, a progressive powerhouse, a State Department of one, became the dominant figure in U.S. politics. After a generation of Grants and Garfields, the modern presidency had arrived in time with the new century. Some critics would come to call its sharp enlargement of executive authority the imperial presidency.

Theodore Roosevelt is among our most relentlessly caricatured public figures. Standing five feet, ten inches, with a thickening trunk, he possessed a brown brush of a walrus mustache, pince-nez eyeglasses to correct severe myopia, and, most flagrantly, flashing white Chiclets-like teeth that, so one New York Times reporter swore, “seem to be all over his face.”

The overall impression is eye-catching if perhaps less than flattering. Photographs and portraits capture a bull neck, bulbous nose, and close-cropped hair that always looked a little on the short side. Belying the heavy set of his frame, TR’s bodily extremities were by contrast a shade off—evident in elfin ears and tiny feet. “Mr. Roosevelt’s clothes were always made for him and always at the same place,” his personal valet noted. “His shoes, too, were made to order. But this was because he was particular about the fit. He had an unusually small foot for a man of his size—indeed, the smallest I have ever seen.”

Those in Roosevelt’s orbit invariably commented on the twenty-sixth president’s unusual energy if not ebullience. “One of his charms lay in a certain boyish zest with which he welcomed everything that happened to him…”

Aside from questions of cobbling and couture, such imperfections compromised Roosevelt’s athletic prowess. Though an avid hiker, tennis player, and college pugilist who liked to spar in the White House for exercise, he struck observers as clumsy, an active sportsman unable to master a single sport (leaving big-game hunting, at which he was perfectly lethal, aside).

“His eye and hand do not go together,” a British ambassador to the United States once remarked confidentially to a colleague. “He is very energetic and full of keenness, but not skillful. He is conscious of the fact and deplores it.” Neither did TR fancy what the writer H. G. Wells called “his unmusical voice,” a thin pitch that Roosevelt blamed in a letter to his mother on “not speak[ing] enough from the chest, so my voice is not as powerful as it ought to be.”

As if in compensation, Roosevelt fairly oozed charisma—Greek for the “gift of grace,” the word denotes a magnetic personality radiating “confidence, exuberance, optimism, a ready smile, [and] expressive body language,” among a host of less easily encompassed qualities. The German sociologist Max Weber thought a rare breed of leaders the likely keepers of charisma, evident in such as Julius Caesar and the emperor Charlemagne, Martin Luther, Mohandas Gandhi, and the oil magnate John D. Rockefeller.

Those in Roosevelt’s orbit invariably commented on the twenty-sixth president’s unusual energy if not ebullience. “One of his charms lay in a certain boyish zest with which he welcomed everything that happened to him,” remembered the writer Margaret Terry Chanler. “I never knew anyone more pleased with things as they were—life was the unpacking of an endless Christmas stocking.”

Edith Wharton, invoking Emily Brontë’s iconic Catherine and Heathcliff, opined, “Our Theodore is a good deal more saga-like than anything in Wuthering Heights,” while the British diplomat Cecil Spring Rice said upon TR’s Pennsylvania Avenue encampment, “It is extraordinary to think of Theodore Roosevelt as President. He will make things hum. I don’t suppose there will be a war but there will be plenty of amusement.”

Audience responses could and did vary. From Cambridge’s rare air, a white-whiskered Charles W. Eliot remembered TR as sui generis: “Of the five Presidents who have visited Harvard while I was President of the University, Roosevelt was the only one who possessed the faculty of attaching all sorts of men to him with a deep sense of personal devotion, although their contact with him might have been but slight. Most of the American Presidents have had nothing of this faculty. Roosevelt possessed it in a supreme degree.”

Less charitably, the historian Henry Adams, descended from America’s most celebrated political dynasty, refused to be blinded by the shine of TR’s swollen star, writing in a memoir that this preening, peacocking “boy” lacked conviction and substance; “he was,” Adams sniffed, looking down his blue nose, “pure act.”

Beyond the political game, Roosevelt, who believed his transient contact with rural peoples while cowpoking after college in the Dakota Territory “enabled me to get into the mind and soul of the average American,” led a very unaverage American life. In youth he had spied from his wealthy grandfather’s Manhattan home the progress of Lincoln’s black-draped funeral procession (then snaking its dramaturgical way through seven states over 1,700 miles) and luncheoned on the Nile River with the ancient Transcendentalist Ralph Waldo Emerson; he had twice toured Europe with his family before the age of fifteen, on one occasion taking a pope by the hand.

While on his first honeymoon he scaled the pyramid-shaped Matterhorn in the Pennine Alps, only sixteen years after it had first been ascended; and late in a not overly long life he nearly died in a Brazilian jungle exploring the previously uncharted River of Doubt, whose dark waters flowed into the Amazon. Given his many overseas trips, it is perhaps fitting that he became the first sitting president to travel abroad—inspecting, in a white linen suit and period-piece boater hat, the progress of the Panama Canal.

A moralist at heart and hungry to put his personal philosophy on record, Roosevelt wrote some three dozen books, among them The Naval War of 1812, The Winning of the West, and The Wilderness Hunter, whose titles accurately convey their author’s interest in, as he called it, “the life of strife.” An insatiable reader, he enjoyed a wide range of literary acquaintances, some of whom—Rudyard Kipling, Owen Wister, and Joel Chandler Harris—became personal friends, and others, including Mark Twain (“a man wholly without cultivation”) and Upton Sinclair (“the socialist”), he never quite cottoned to.

All of life is a compromise, of course, and Roosevelt, “saga-like” leanings to the contrary, seemed to grasp this fact as well as anyone.

Most Americans—including scholars—have liked Roosevelt. In the parlor game of presidential rankings, he often comes in fourth, just below the de rigueur demigods of Abraham Lincoln, George Washington, and TR’s fifth cousin Franklin Roosevelt. It is from contrary opinions, however, that we often come upon insight, balance, and unexpected perspective. Writing in 1948 in the blasted shadow of European dictatorships, the Holocaust, and the unsettling popularity of mass propaganda, the historian Richard Hofstadter cannily observed of Roosevelt in his influential study The American Political Tradition:

Despite his sincere loyalty to the democratic game, this herald of modern American militarism and imperialism displayed in his political character many qualities of recent authoritarianism—romantic nationalism, disdain for materialistic ends, worship of strength and the cult of personal leadership, the appeal to the intermediate elements of society, the ideal of standing above classes and class interest, a grandiose sense of destiny, even a touch of racism.

A generation earlier, the jurist Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., appointed to the Supreme Court by TR, recognized his patron’s astonishing presence, but qualified it with caution: “He was very likeable, a big figure, a rather ordinary intellect, with extraordinary gifts, a shrewd and I think pretty unscrupulous politician. He played all his cards—if not more.”

Invariably, this harbinger of American Century wars and interventions was disappointed by not having a crusade of his own to attend. How it bothered him to watch a mere professor, the former Princeton University president Woodrow Wilson—initially angling for neutrality in what Roosevelt called a “diluted mush policy”—luck into the Great War. His own administration, rather, oversaw a period of comparative peace.

And thus, unlike the supreme trio who rank ahead of him in the presidential sweepstakes, and who are identified most clearly with the Revolutionary, Civil, and Second World Wars, Theodore Roosevelt holds his place principally, ironically, because of his progressivism, domestic reforms, and successful effort to mediate an end to the Russo-Japanese War. All of life is a compromise, of course, and Roosevelt, “saga-like” leanings to the contrary, seemed to grasp this fact as well as anyone.

“Whatever comes hereafter,” he wrote a British friend, shortly before exiting the White House with what can only be described as mixed feelings, “I have had far more than the normal share of human happiness.”

__________________________________

Excerpted from In the Arena: Theodore Roosevelt in War, Peace, and Revolution by David S. Brown. Copyright © 2025 by David S. Brown. Reprinted by permission of Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, LLC.

David S. Brown

David S. Brown teaches history at Elizabethtown College in Pennsylvania. He is the author of several books including The Last American Aristocrat; Paradise Lost: A Life of F. Scott Fitzgerald; and Richard Hofstadter: An Intellectual Biography.