He left the boy outside its own front door. Farewell to it, and good luck to it. From here on in it would be squared shoulders and jaws, and strong arms and best feet forward. He left the boy a pile of mangled, skinny limbs and stepped through the door a newborn man, stinging a little in the sights of the sprite guiding his metamorphosis. Karine D’Arcy was her name. She was fifteen and a bit and had been in his class for the past three years. Outside of school she consistently out- classed him, and yet here she was, standing in his hall on a Monday lunchtime. And so the boy had to go, what was left of him, what hadn’t been flayed away by her hands and her kisses.

“You’re sure your dad won’t come home?” she said.

“He won’t,” he said, though his father was a law unto himself and couldn’t be trusted to follow reason. This morning he’d warned that he’d be out and about, so the kids would have to make their own dinner, though he’d be back later, trailing divilment and, knowing the kindness of the pit, a foul temper.

“What if he does, though?”

He took his hand from hers and slipped it round her waist.

“I don’t know,” he said. Oh, the truth was raw, as raw as you could get, unrehearsed words from a brand-new throat.

He was fifteen, only just. If she’d asked him the same question back before they’d crossed this threshold he would have answered according to fifteen years build-up of boyish bravado, but now that everything had changed he couldn’t remember how to showboat.

“It’ll be my fault anyway,” he said. “Not yours.”

They were supposed to be in school, and even his dad would know it. If he came home now, if, all lopsided with defeat, the worse for wear because of drink, or poker or whatever the fuck, it’d still take him only a moment to figure out that his son was on the lang, and for one reason only.

“Here it’d be yours,” she said. “But what if he told my mam and dad?”

“He wouldn’t.” It was as certain as the floor beneath them. His father was many things, but none of them responsible. Or bold. Or righteous.

“Are you sure?”

“The only people my dad talks to live here,” he said. “No one else would have him.”

“So what do we do now?”

The name of this brave new man, still stinging from the possibilities whipping his flesh and pushing down on his shoulders, was Ryan. In truth, his adult form wasn’t all that different to the gawky corpse he’d left outside; he was still black-haired and pale-skinned and ink-eyed. “You look like you’re possessed,” shivered one of the girls who’d gotten close enough to judge; she then declared her intent to try sucking the demon out through his tongue. He was stretching these past few months. Too slow, too steady, his nonna had sighed, the last time she’d perused his Facebook photos. She was adamant he’d never hit six feet. His mother was four years dead and his father was a wreck who slept as often on the couch as he did in his own bed. Ryan was the oldest of the wreck’s children. He tiptoed around his father and made up for it around everyone else.

Something didn’t fit about that. Of course, men of any age were entitled to flake around the place giving digs to anyone who looked like they might slight them, and that was certainly how the wreck behaved: hollow but for hot, cheap rage, dancing between glory and drying-out sessions in miserable rehab centres a million miles from anywhere. Even when Ryan dredged up the frenzies required by teachers’ scorn or challenges thrown down by bigger kids, he knew there was something very empty in the way the lot of them encouraged him to fight. He’d been on the lookout for something to dare him to get out of bed in the morning, but he’d never thought it could have been her.

She was part of that group of girls who wore their skirts the short- est and who commandeered the radiator perches before every class and who could glide between impertinence and saccharine familiarity with teachers. He’d never thought she would look at him as any- thing but a scrapper, though he’d been asking her to, silently, behind his closed mouth and downturned eyes, for fucking years.

Three weeks before, on the night of his birthday, she had let him kiss her.

He’d been in one of his friends’ cars—they were older than him, contemporaries of his sixteen-year-old cousin Joseph, who knew enough about Ryan to excuse his age—when he’d spotted her standing outside the doors of the community centre disco, laughing and trembling in a long black top and white shorts. He’d leaned up from the back seat and called her from the passenger window, and he didn’t even have to coax to get her clambering in beside him. Dumb luck that she was in the mood for a spin. And yet, a leap in his chest that tempted him to believe that maybe it was more again: dumb luck and trust. She trusted him. She—Jesus!—liked him.

They’d gone gatting. There were a couple of cans and a couple of joints and a cold, fair wind that brought her closer to his side. When he’d realised he couldn’t medicate the nerves, he’d owned up to how he felt about her by chancing a hand left on the small of her back, counting to twenty or thirty or eighty before accepting she wasn’t going to move away, taking her hand to steady his own and then finally, finally, over the great distance of thirty centimetres, he caught her mouth on his and kissed her.

In the days that followed they had covered miles of new ground and decided to chance making a go of it. They had gone to the pictures, they had eaten ice cream, they had meandered at the end of each meeting back to her road, holding hands. And lest they laid foundations too wholesome, they had found quiet spaces and dark corners in which to crumble that friendship, his palms recording the difference between the skin on her waist and on her breasts, his body pushing against hers so he could remember how her every hollow fit him.

Now, in his hall on a Monday lunchtime, he answered with a question.

“What do you want to do?”

She stepped into the sitting room and spun on one foot, taking it all in. He didn’t need to stick his head through the frame to know that the view was found wanting. His father’s ineptitude had preserved the place as a museum to his mother’s homemaking skills, and she had been as effective with clutter as the wind was with blades of grass.

“I’ve never been in your house,” she said. “It’s weird.”

She meant her presence in it, and not the house itself. Though she wouldn’t have been far wrong; it was weird. It was a three-bedroom terraced so cavernous without his mother he could barely stand it. It was a roof over his head. It was a fire hazard, in that he thought sometimes he could douse it in fuel and take a match to it and watch it take the night sky with it.

She knew the score. He’d admitted his circumstances in a brave move only a couple of days before, terrified that she’d lose it and dump him, and yet desperate to tell her that not every rumour about his father was true. On the back steps of the school, curled together on cold concrete, he’d confessed that yeah, he clashed with his dad, but no, not in the way that some of the more spiteful storytellers hinted at. He’s an eejit, girl, there’s only the weight in him to stay upright when he’s saturated, but he’s not . . . He’s . . . I’ve heard shit that people have said but he’s not warped, girl. He’s just . . . fucking . . . I don’t know.

She hadn’t run off and she hadn’t told anyone. It was both a load off and the worst play he could have made, for it cemented his place on his belly on the ground in front of her. On one hand he didn’t mind because he knew she was better than him—she was whip- smart and as beautiful as morning and each time he saw her he felt with dizzying clarity the blood in his veins and the air in his lungs and his heart beating strong in his chest—but then it pissed him off that he couldn’t approach her on his own two feet. That he was no more upright now than his father. That uselessness was hereditary.

There was no anger now, though. He had left it outside the front door with his wilting remains.

She held out her hand for his. “You gonna play for me?”

His mam’s piano stood by the wall, behind the door. It could just as easily have been his. He’d put the hours in, while she fought with his dad or threatened great career changes or fought with the neighbours or threatened to gather him and his siblings and stalk back to her parents. She used to pop him onto the piano stool whenever she needed space to indulge her cranky fancies, and in so doing had left him with ambidexterity and the ability to read sheet music. Not many people knew that about him, because they’d never have guessed.

He could play for Karine D’Arcy, if he wanted to. Some classical piece he could pretend was more than just a practice exercise, or maybe one of the pop songs his mother had taught him when she was finding sporadic employment with wedding bands and singing in hotel lobbies during shitty little arts festivals. It might even work. Karine might be so overwhelmed that she might take all her clothes off and let him fuck her right there on the sitting-room floor.

Something empty about that fantasy, too. The reality is that she was here in his house on a Monday lunchtime, a million zillion years from morphing into a horny stripper. That’s what he had to deal with: Karine D’Arcy really-really being here.

He didn’t want to play for her. Anticipation would make knuckles of his fingertips.

“I might do later,” he said. “Later?”

He might have looked deep into her eyes and crooned Yeah, later, if he’d had more time to get used to his new frame. Instead he smiled and looked away and muddled together Later and After in his head. I might do After. We have this whole house to ourselves to make better. There was going to be an After. He knew it.

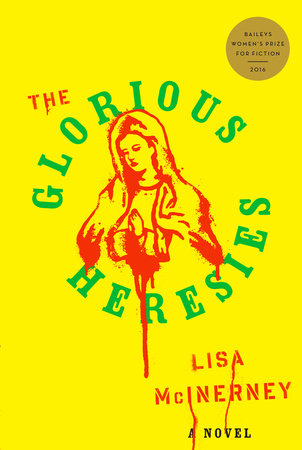

From THE GLORIOUS HERESIES. Used with permission of Tim Duggan Books. Copyright © 2016 by Lisa McInerney.