The Ghost of Christmas Cheer

How the Holiday's Reception Has Changed Since Dickens' Time

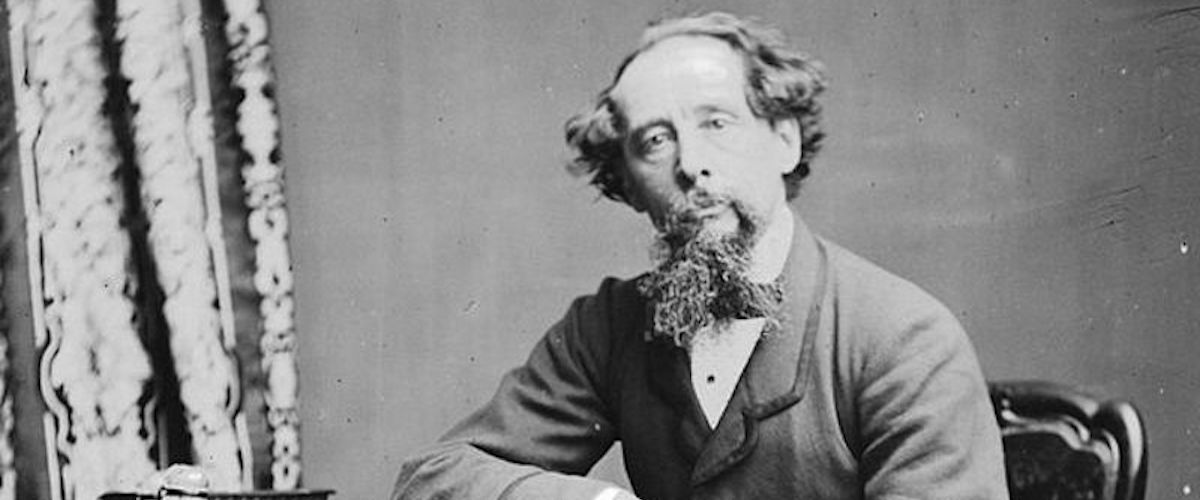

A 21st-century writer who sits down to tell a story that takes place during the Christmas season looks back on Charles Dickens not only with admiration―Dickens is, hands down, the literary laureate of the holiday―but also with a generous dollop of envy. Unlike the writers of today, Dickens sent his holiday stories off to a readership for whom Christmas was bright, shiny, reverent, welcome, and new, while we poor modern scribblers have to engage the attention of people who probably regard Christmas with considerably less seasonal cheer and, perhaps, a bit of dread.

When you celebrate Christmas through the imagination of Dickens, it’s a blazing fire of good cheer, hot toddies, and pristine snow (although there were actually very few white Christmases in England while Dickens was alive). It looks and feels like a Christmas card from the past or like the world you see in a snow globe. It looks―well, it looks like Christmas, a Christmas memory. Today, the most vivid Christmas memory is likely to arrive with the January credit card statements.

There was a good reason for all of that Victorian seasonal enthusiasm. The Victorians pretty much invented—or reinvented—Christmas, and while they were at it they also produced the season’s leading literary champion. Charles Dickens harnessed the energy of his age’s fervent enthusiasm for its shiny newborn holiday from the very beginning: his first novel, The Pickwick Papers, offers not one but two Christmas stories, the conventional, roaring-fire-and mulled-wine tale “Christmas at Dingley Dell” and the Christmas Eve ghost fantasia, “The Story of the Goblins Who Stole a Sexton.”

Pickwick was a global sensation, making Dickens, at the age of 24, the world’s most famous and celebrated writer. Six years later, however, in 1843, he was in a sort of slump (for him, anyway), exacerbated by the uniquely bitter experience of having to continue to write a serialized book, Martin Chuzzlewit, when its first sections had already been declared a critical flop and a public yawn―so much of a yawn, in fact, that his publishers ordered him to return his advance. His bank accounts were suddenly precariously light, and he and his wife were expecting their fifth child. During this period of literary and financial misery, he thought of the book he called “his little carol.”

When released, “A Christmas Carol” was a sensation. It sold its entire first printing of 6,000 copies almost instantly and was plagiarized in all of the day’s available media formats, which is to say it was reprinted in pirate editions and adapted for unauthorized stage productions, none of which put a farthing in Dickens’ pocket. Still, his readers’ enthusiasm prompted him to a lifelong literary engagement with Christmas: there was a Christmas book a year for several years, and after he abandoned that scheme, he still set dozens of stories during the holiday season. Dickens had found one of his great themes.

But why were these stories greeted so enthusiastically? Why was the reading public so eager to follow his characters into the promise and occasional perils of Christmas?

Because Christmas had all but disappeared in England and was in the process of being reinvented. To the Victorians, it was novel, it was the Victorian equivalent of cool. It was―well, maybe not―edgy. Under Oliver Cromwell, the Puritan Parliament had banned the celebration of Christmas altogether in 1644. The ban ended with the return of the monarchy, but the bloom was gone. Many ministers discouraged it―in fact, several cottages burned down when some poor matron, surprised in the middle of cooking Christmas dinner by an impromptu visit from her clergyman, snatched the red-hot cooking pot off the fire and slipped it beneath the bed, with predictable results.

Then, when religious strictures gradually relaxed and the holiday might once again have taken root, the Industrial Revolution disrupted life all over England, snatching men and women (and tens of thousands of children) out of the villages to labor in the booming manufacturing centers, breaking up communities, fracturing traditions, and absolutely devouring holidays. In 1825, the Bank of England closed for 47 holidays each year; in 1834, three years before Victoria’s coronation, there were exactly four bank holidays, and none of them was Christmas. In the early 1820s, about a decade after Dickens’ birth, the poet and essayist Leigh Hunt described Christmas as “scarcely worth mention.”

But the Industrial Revolution was a bonanza for the fortunate few and, indirectly, for both Dickens and Christmas. It created a whole new class, an economic upper class, that took an uneasy place beside the traditionally well-born. Like many people throughout history who attain social prominence through effort rather than through bloodlines, this newly enriched upper class was enchanted by tradition and wanted to buy all of it they could get their hands on. A glamorous young family now lived in Buckingham Palace and Victoria’s German regent, Prince Albert, brought with him the tradition of the tannenbaum, the Christmas tree. Christmas parties and Christmas dinners became fashionable, even essential to stake out one’s place in society. Celebrating Christmas became the thing to do.

And directly into this boiling pot of well-heeled enthusiasm, Dickens threw “A Christmas Carol.” It was the book everyone wanted. The timing was impeccable; to suggest a financial equivalent would be like buying stock in Standard Oil the week the first Ford rolled off the assembly line. “A Christmas Carol” became what would later be known as a water-cooler topic, and Dickens re-ascended the hierarchy of British fiction. Christmas was triumphant, and during a very short period, Dickens’ readers invented, rediscovered, or adapted almost all the holiday’s modern trappings: the tree, Christmas dinner, cards, presents, carols, Father Christmas/Santa Claus, and on and on.

Whereas today . . .

Shopping malls with multiple Santas servicing the wish-making needs of shoppers in various anchor stores. The spiritual advisers of the Chamber of Commerce putting up Christmas decorations before we’ve cooked Thanksgiving dinner. Commercials in all media dangling bright desirables in the faces of kids whose parents can’t afford them. A sound track composed by that hit retail trio of canned music, sleigh bells, and cash registers. It’s a sort of evolution in reverse, from an event (whether you believe it’s literal or aspirational) of the purest innocence and on the most humble scale—a manger, some animals, a mother, a father and a child—that has been transformed into a multi-billion-dollar commercial orgy, the success of which is gauged not on spirit but on spreadsheets.

We might be beyond even that era now, too. Malls, which for decades were so central to the holiday shopping experience, are in decline, replaced by the ever-present temptation of online outlets, always as close as your index finger. Everything we buy for our loved ones now becomes an integer in an algorithm that dictates what we’ll be pitched in the year to come. The gift that keeps on giving . . .

And in popularizing Christmas to increase its profitability, we’ve set the hacks to work on the legend: Santa can teach reindeer how to fly, create a sled as light as air, and make a sack that holds toys for every Christmas-observing child on the planet, but he can’t navigate in the fog? Please. As a child, I fretted for years over whether Scrooge was a duck. The first time I heard the song “I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus” I was nine, and I thought, “Is this something else I have to worry about?”

So a major challenge for a writer who sees Christmas this way and who regrets the loss of the open-hearted generosity that used to be the emotional key to the holiday is how to avoid being too sour. Not a challenge Dickens would have recognized, even though his book was written partly in anger.

When he sat down to write the “Carol” Dickens was deeply involved with an effort to help the smallest victims of the Industrial Revolution, the nation’s poorest children. Only a few months earlier, he had shared a stage with Benjamin Disraeli in an event that raised questions and offered answers about the care and education of poverty’s children. Tiny Tim stands in for some of these unfortunates, but their most memorable incarnations are the filthy boy and girl—“yellow, meager, ragged, scowling, wolfish” that the Ghost of Christmas Present introduces as Ignorance and Want. Dickens’ theme is sounded in trumpets when a horrified Scrooge asks, “Have they no refuge or resource?” and the Spirit quotes Scrooge’s own words: “Are there no prisons? Are there no workhouses?”

Dickens and the Victorians were responsible for putting children at the center of the Christmas celebration, and probably the most positive way to look at the modern holiday is to recognize that no amount of blinky lights, tinsel, or reindeer with neon noses can actually corrupt the impulse to give something wonderful to someone we love―perhaps a child—to turn love, for a moment or two, into something palpable and visible, to yield to an impulse that has no objective but to lift someone’s heart. This impulse existed before Christmas, and for a while it animated Christmas, and if you cut through the modern clutter, it’s still there. It’s something to look at closely; it’s something worth writing about.

Even if we’ll never do it half as well as Dickens.

Timothy Hallinan

Timothy Hallinan is an Edgar- and Macavity-nominated mystery novelist who lives in Los Angeles and Bangkok and devotes his website to helping writers finish their books.