The first thing to say about Nabil, should we wish to describe him, is that he is an optimistic man – a quality all the more striking as it has just about vanished from the village of Al-Walaja, whose residents are distinguished by their ability to find a problem for every solution. Tell them you’ve worked out how to bring water to the fruit trees next year, and they’ll poke ten holes in your plan. Say you’ve found a way to get the children to school safely in winter, and they’ll turn winter into a battlefield. Not so Nabil – a man who, through sheer persistence, can get around any problem; he can’t even remember when he last used the word problem. His solutions may falter, they may take aeons to achieve, but they always come off in the end.

You might say it’s a quality passed down the generations.

His great-grandfather Salem managed to escape certain death during the Nakba, when he and the other villagers found themselves trapped in the mosque. All the men were killed except for him, as he had found an opening in the wall of the mosque’s storeroom and hid there among the old rugs until it was all over. Then he ran and didn’t stop until, after sixty miles, he reached the hills of Amman.

His father’s brush with certain death came in the Second Intifada. His phone had rung and saved his life (or so he daily swears), just before bullets came piercing through the wall of the room he was painting in Ramallah. As the caller remains unknown to this day, he could almost swear it was a direct call from God.

Both sources, perhaps, of Nabil’s sense that all would be well in the end.

When word began to spread that the wall was due to run through his village and that his house alone would lie beyond it, cut off from his land and the homes of his relatives, he saw no issue there, and he could not understand why his wife kept howling that their livelihood was ruined, their wealth gone up in smoke, their family finished. Nabil would find a way out: he was sure of it.

As soon as digging began, in 2002, Nabil set to work. He read all the reports, the surveys and assessments, studied the maps and plans, and memorised the names of all the neighbourhoods, villages and towns the wall – all 730 kilometres of it – would cut in half. He even walked the length of the Green Line, which separates the West Bank from Israeli territory, observing the construction workers as they unloaded the large blocks of cement and slowly closed off the horizon.

Every day he’d return home and record the information he had gathered in his notebook, his black box:

On the Palestinian side, the wall consists of six coils of barbed wire, followed by a deep trench, then a dirt road for the passage of patrols, then an electronic fence three metres high.

On the Israeli side, it consists of a paved road with sandy lanes on either side, barbed wire, and electronic alarms. At certain points, the barrier is as wide as 60 metres. As for the concrete wall, it is found only in densely populated areas. It is 8 metres high.

To support his optimistic view of things, he’d present his wife with figures: 166 houses demolished to build the wall; 49,291 metric dunams of land confiscated, most of which had been used for agriculture. How lucky they were, he insisted, that their house was only separated from the village and not demolished, that their land was only cut off by the wall and not confiscated. That as long as it was somewhere, it was everywhere. Assuring her all the while that he would find the gap to let him through. For wherever there is a wall, there must be a gap.

For ten years, Nabil left his home in the morning and returned in the evening, hunting for the gap, trying theory after theory as to where it might be. However strong the wall, it seemed inevitable that the climate, animals, people, even the earth itself expanding and contracting would have forced a crack in it. Nabil spent long hours envisioning the moment he would slip into the gap, having made sure no one was guarding it or watching from afar, though it was also possible, he reasoned, that there were trap openings created by the soldiers to ensure their control over any gaps that may exist or to test their new weapons.

Still, he would study all options so thoroughly that none could escape him. He even adopted a small dog that took a shine to him on the road, but decided not to form any sort of emotional bond with it, not even to give it a name, so as not to become attached. He would send it ahead of him into the gap, when he found it, and wait to see what happened. But after a year of going back and forth in the company of the dog (his children, unbeknown to him, had named it Biscuit), he grew so fond of it that he could no longer think of parting. He even built a kennel for it opposite his home and came to think of it as his closest companion, as did his four children and even his wife, who had lost her mind when she first saw it, declaring that the cruelty of life had sent her, instead of family and land, a dog and a mad husband who spent his whole time looking for a gap.

One day it occurred to him that the gap might be at the top rather than the bottom, as he had imagined all this time, and he felt the answer was near. He found an area outside the city of Tulkarm almost empty of residents and saw no patrols in the ten days he spent observing the road. For three months he experimented with ideas for a light ladder he might carry across a long distance, and ended up assembling one from the olive tins which had lain empty since the wall was built, as the trees were now beyond reach. Inconspicuous, easy to dismount, his ladder was ready. He waited for the promised day when he would carry it in a long bag he had bought for this purpose from the market in Jenin.

He tried not to meet anyone’s eye as he walked, and it was curious that no one looked in his direction either. Then he noticed that many men and women and even schoolchildren were carrying bags similar to his, and it seemed to him that they too were hiding something, but no one looked at anyone else or asked where they were going. He reached the point he had spotted, waited quarter of an hour in case someone was watching him, then he began to remove the ladder piece by piece and set it up, Lego-style, against the wall. Having scaled it, he found he was ten centimetres short of reaching the barbed wire at the top. He had not been up there a few moments when an IDF patrol showed up and arrested him immediately.

After three years, Nabil was finally released.The gap preyed on his mind throughout his detention, and for once in his life he felt there was no way out of the predicament in which he found himself. He seemed to see things for the first time as they really were, as if he had been given a new pair of eyes: he saw his house standing alone surrounded by tall cement walls, and he saw himself without work or land or family. Things dawned on him: that his children wore the same clothes they had passed between them for years. That his wife’s black shoes had turned grey. That it was years since he last took his family out for falafel.

His wife sold everything they owned and found work in the neighbouring villages making pickles and cheese for one of the women’s centres, and was able to milk her sheep and see to their basic needs, but it killed her to go on living in the isolated house. He thought she was bound to leave him and take their children to live in one of the surrounding villages. And that he, too, would be forced to leave the house.When at last Nabil walked out of prison, he resolved to put the gap out of his mind for good – to give up the very thought of its existence. He entered his home broken, another man entirely. At night, when the children had gone to sleep on their mattresses side by side, his wife slowly came near. This is it, he thought. She is about to leave me for good.

Instead, from under her belt, his wife pulled out the black notebook.

‘I searched everywhere on this side. Now I’m sure: the gap must be on the other side. I heard Umm Muhammad say to her neighbour that her son managed to find an opening on the south side, and that dozens of people have come and gone without being caught.’

Life had drained from Nabil’s eyes – and from his hands and cheeks and guts. But his wife’s words revived him in an instant. He leapt out of his seat and fell on the pages of the black notebook, which was filled with names and signs and maps, only to discover that he had indeed been looking in the wrong direction. He kissed his wife’s throat – a soft burble against the night’s hush. In the morning the whole family went looking for the gap.

__________________________________

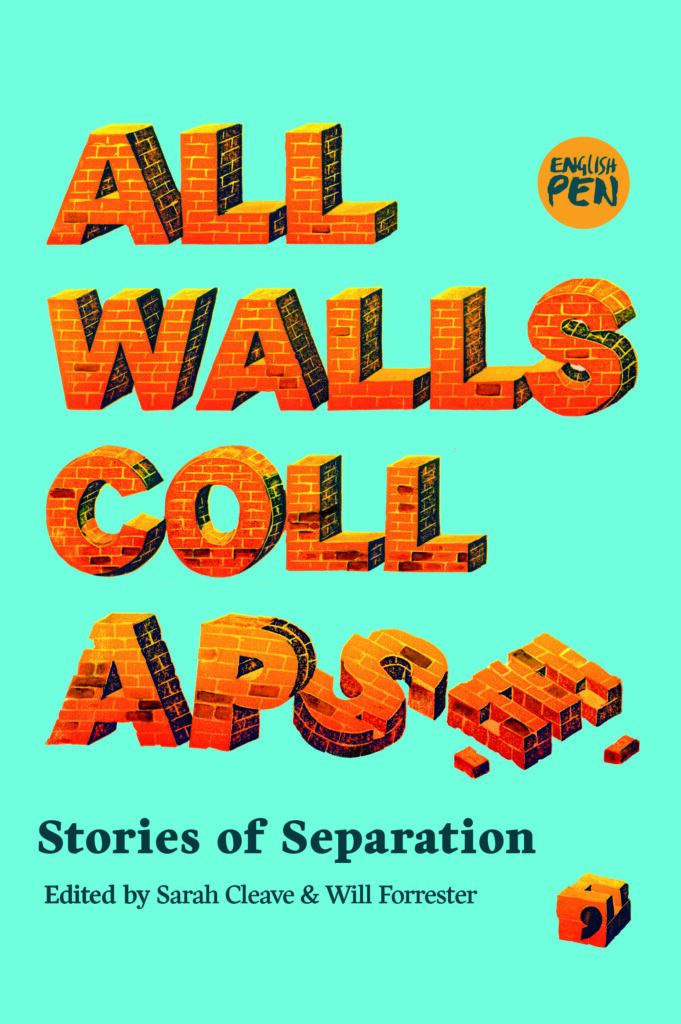

“The Gap” by Maya abu al-Hayat, translated from the Arabic by Yasmine Seale. From the anthology All Walls Collapse: Stories of Separation, edited by Will Forrester and Sarah Cleave. Used with permission of the publisher, Comma Press. Copyright 2022 by Maya abu al-Hayat. Translation copyright 2022 by Yasmine Seale.