The Future (and Past) is Human (and Machine)

Alan Lightman and Martin Rees Explore How Science and Technology Have Shaped Our World—And What Comes Next

On July 8, 1943, Thomas W. Wallace, only seven months into his job as lieutenant governor of New York, came down with pneumonia. He was quickly driven to Ellis Hospital in Schenectady, where he was placed in an oxygen tent. For a while, his condition improved. But then he suffered a relapse. Despite being given an injection of serum rushed from state laboratories in Albany, a bronchoscopy procedure to clear the congestion in his lungs, and three blood transfusions, Wallace passed away a few days later, with his wife and two young children at his bedside. He was forty-three years old.

By today’s standards, Mr. Wallace died young. But, in fact, people born in 1900 like Mr. Wallace had a life expectancy of only forty-seven years. Little more than a century later, life expectancy had dramatically increased to seventy nine years—all due to a better understanding of microscopic germs as the cause of infectious diseases, public health measures, and the discovery and application of antibiotics. Indeed, if Mr. Wallace had been born only a few years later, his pneumonia might have been easily cured with the newly available penicillin, discovered in 1928 by a Scottish biologist named Alexander Fleming.

People today are not only living longer. We’re wealthier. At the beginning of the twentieth century, 65 percent of the world’s population lived in extreme poverty, defined by the World Bank as less than $2.47 per person per day in 2022 dollars. Today, the fraction of people worldwide living in that condition is about 9 percent.

Prometheus was chained to a rock for stealing the fire of the gods and giving it to human beings. But, in fact, we have made fire ourselves.

What happened to bring about such astonishing increases in human life and wellbeing? Science and technology. In addition to advances in biology and medicine, brought about by such people as Louis Pasteur and Alexander Fleming, the first and second Industrial Revolutions, beginning in the mid-eighteenth century, vastly increased food production, transportation, and the creation of goods. Crop rotation, selective breeding, mechanized plows, and synthetic fertilizers increased wheat production from 0.5 tons per hectare (2.5 acres) to 8 tons per hectare today.

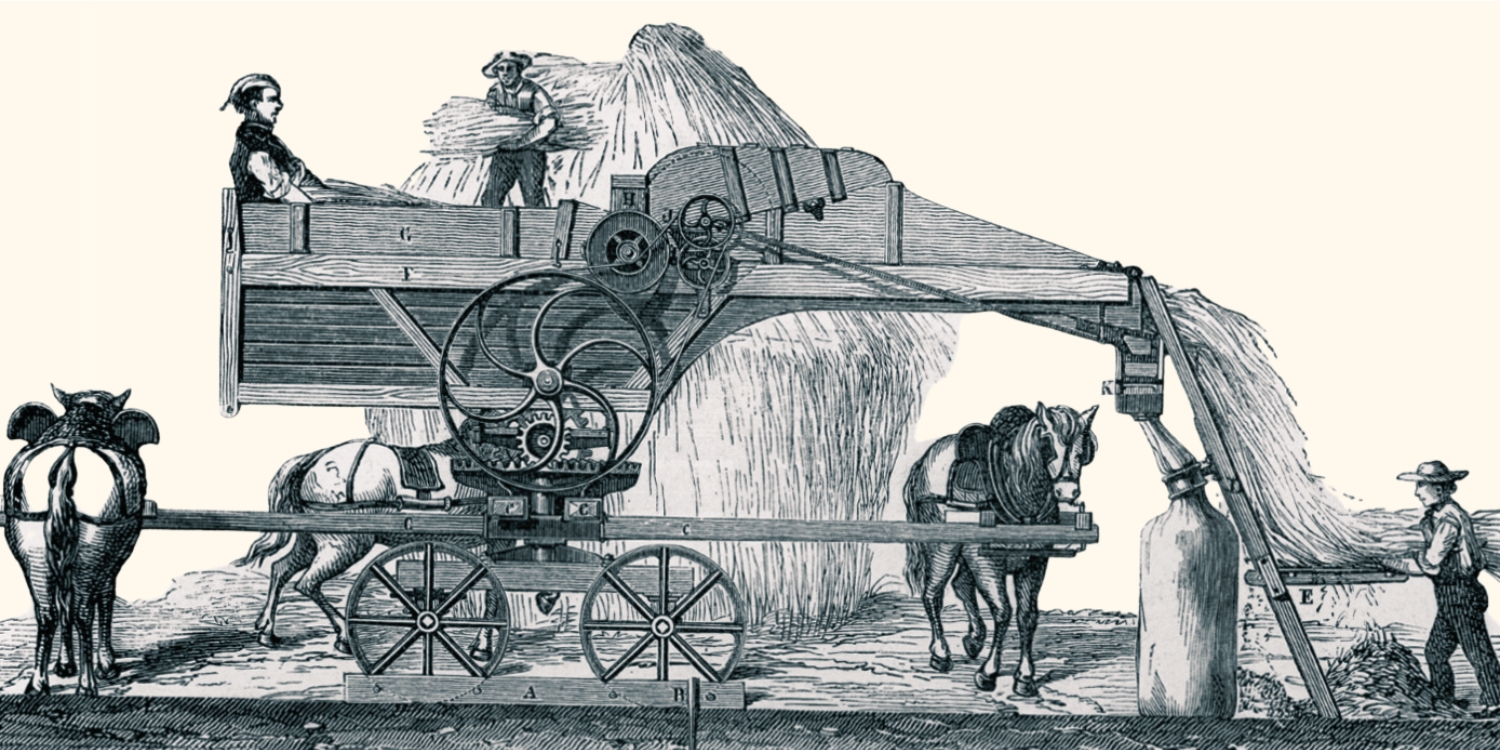

Cyrus McCormick’s threshing machine led to a 500 percent increase in wheat harvesting per hour. Isaac Singer’s sewing machine lowered the time to make a shirt from fourteen hours to one hour. The newly invented electric dynamo generated power for factories and industry. The British inventor Henry Bessemer discovered a process for greatly improving the production of steel, used in plows and almost everything else. Railroads. The cotton gin. The seed drill. Tractors. Electricity.

Ideas and techniques travel fast from the lab bench to the engineering shop to the industrial warehouse. In 1832, the British physicist Michael Faraday discovered the operating principle for electromagnetic generators and motors. In 1858, the BelgianFrench engineer Étienne Lenoir invented the first commercial internal combustion engine. In the period 1856–1863, the biologist and botanist Gregor Mendel discovered the laws of biological inheritance. Then, in the late 1860s, the chemist Friedrich Miescher identified the molecule DNA, eventually leading to the unraveling of its structure by Rosalind Franklin, James Watson, and Francis Crick in 1953.

Today, DNA therapy is used to treat such diseases as Leber congenital amaurosis, which causes blindness, and various blood cancers such as acute lymphoblastic leukemia and large B cell lymphoma. In the future, gene therapies may be used to treat cystic fibrosis, hemophilia, sickle cell disease, and many other diseases. In the early twentieth century, Einstein formulated equations for the peculiarly relative flow of time, now an indispensable part of the workings of all GPS systems.

We have labeled ourselves Homo sapiens. It means “wise humans.” Over thousands of years of our history, no other activity is more worthy of that name than our science and technology. We are thinkers, we are dreamers, we are tool makers, we are inventors, we are builders, we are creators. Prometheus was chained to a rock for stealing the fire of the gods and giving it to human beings. But, in fact, we have made fire ourselves. Without help from the gods, we have created steam engines and internal combustion machines and antibiotics. If an intelligent being were monitoring our planet through a giant tele scope from the far reaches of space—even without any inkling of Alexander Fleming or Michael Faraday or Albert Einstein—he/she/it would observe a remarkable transformation of the planet: first the gradual organization of the land into the neat rows of agricultural fields, then buildings, then the congregation of buildings into cities, then a proliferation of points of light on the surface of the Earth, then radio signals, then large machines flying in the air . . .

We have made our world, and we have made it with science and technology. We’re so accustomed to the science and technology around us that we hardly notice. It has become almost invisible. But consider our electric lights, our automobiles, our refrigerators and washing machines, our televisions, our computers and smartphones. As little as a century ago, none of these items were available, some not even dreamed of. Or consider the extremely rapid development of vaccines during the recent COVID pandemic. We live in a built world, and we are the builders.

Right under our noses, Homo sapiens is transitioning into a new type of species that might be called Homo techno.

The foundation for most of our medicine and technology is science. Pasteur and Fleming and Faraday and Franklin and Einstein were scientists. But beyond its many practical applications, science has changed our understanding of the cosmos and our place in it. Science has given us new ways to think about the world and about ourselves.

Once we humans believed that our planet was the center of the universe. Discoveries in astronomy have shown that, instead, it is our Sun that is the center of our solar system, which itself resides on the outskirts of an ordinary galaxy, which itself is one among zillions of galaxies. Once we thought that we were different from all other living creatures, and that the world was made for our benefit. Following the ideas of Darwin, discoveries in biology and paleontology have shown that we evolved from earlier life-forms. We Homo sapiens, like all other animals, are part of a grand evolutionary process that can be traced back to the beginnings of life on Earth. We are part of the overarching unity of the entire web of life on our planet.

The understanding of DNA has allowed us to gaze into our very construction, removing much of the mystery of living organisms. Discoveries in brain science have shown us that our emotions, our angers and sympathies, even our personalities are controlled by chemicals within the three pounds of mushy mass in our skulls. The discovery of the expansion of the universe and its Big Bang beginnings has eliminated the long-held belief of an unchanging and eternal cosmos. The discovery of relativity and quantum physics has demonstrated that nature at high speeds and small distances behaves in ways very foreign to our sensory perceptions. Yet we have harnessed those discoveries in building our GPS systems and our computers. In effect, science and its applications have greatly extended our human sensory apparatus. Science and its applications have made us super beings.

What about our place in the cosmos, and our future as human beings? Astronomy, in particular, has provided an awareness of the huge spans of space and time in the universe and also the vast amount of time that lies in the future. Even people who accept Darwin’s ideas tend to think that human beings are in some sense the culmination, the end point, of evolution. Astronomers know, however, that the time lying ahead is at least as long as the time that has elapsed up until now. In fact, according to our best thinking, it could be in nite.

We should not think of human beings as the final form of life. There is as much potential for evolution in the future as there has been to get from a bacterium to us. But it is not evolution in the Darwinian sense, driven by the forces of natural selection. We have bypassed those forces. We are modifying our evolution by our own hand. We are remaking ourselves. Right under our noses, Homo sapiens is transitioning into a new type of species that might be called Homo techno. And the change is happening not over millions of years. It’s happening in single human lifetimes, by our own inventions and technology.

We have already seen small examples of such techno evolution in our eyeglasses and hearing aids. In 2015, a man named Eric Sorto, paralyzed from the neck down, had a computer chip implanted in his brain that allowed him to move a robot arm by pure thought. And only recently, new large language models in artificial intelligence, such as ChatGPT, promise to greatly expand our ability to manipulate and employ enormous quantities of data. At the University of Cincinnati in the United States, researchers at the eXtended Reality Lab have created an embodied/virtual reality system in which people exercising on a treadmill alone in their house have the experience of being in a gym, surrounded by other people also exercising. Of course, such high-tech innovations, providing the illusion of a social environment, have both pluses and minuses.

And we can hardly foresee all the changes that advanced artificial intelligence will bring about, both the benefits and the dangers.

But far more awaits in the future. In a century or less, we may have special lenses implanted in our eyes that do what our external detectors do now, allowing us to see X-rays and other frequencies of light much higher than the visible part of the electromagnetic spectrum. With this technology and off the shelf X-ray emitters, we will be able to see through walls and many other surfaces that ordinary light cannot penetrate.

A hundred years from now, we may have computer chips implanted in our brains that connect them directly to the internet. In such a situation, we may need only think of a piece of information we need, and it will be instantly transmitted to our brains. Using the same technology, we might be able to communicate directly with the minds of other people through the internet. (Such a scenario would raise vast new issues of privacy and intellectual property and probably require new kinds of laws and legal constructions.)

Fifty years from now or less, we may have tiny robots, the size of red blood cells or smaller, that can be injected into our bodies to kill cancer cells, deliver drugs with highly targeted precision, repair damaged or faulty DNA, and greatly enhance our immune system. With developments in neuroscience and the understanding of memory storage, we may have brain implants that teach us new languages in minutes. Words in Chinese or Swahili could be streamed to our brains in real time. And if we wish to utter those words, instructions for the unfamiliar movements of mouth muscles could also be streamed in real time. And we can hardly foresee all the changes that advanced artificial intelligence will bring about, both the benefits and the dangers.

In sum, human beings in the future, Homo techno, will be part human and part machine. These cyborg beings will have vastly greater physical and mental abilities than we do now. We cannot imagine what we will be even a hundred years in the future, just as people in the year 1900, the year that Thomas Wallace was born, could not have imagined cell phones and antibiotics. All of these developments, now and in the future, will continue to change how we understand ourselves and our place in the world. These advances are not only material. They are also about ideas. They are part of our human culture, and it is a universal culture, transcending language and ethnicity and national boundaries.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Shape of Wonder by Alan Lightman and Martin Rees. Copyright © 2025 by Alan Lightman and Martin Rees. Excerpted by permission of Pantheon, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Alan Lightman

Alan Lightman earned his PhD in physics from the California Institute of Technology and is the author of seven novels, including the international best seller Einstein’s Dreams and The Diagnosis, a finalist for the National Book Award. His nonfiction includes The Accidental Universe, Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine, and Probable Impossibilities. He has taught at Harvard and at MIT, where he was the first person to receive a dual faculty appointment in science and the humanities. He is currently a professor of the practice of the humanities at MIT. He is the host of the public television series Searching: Our Quest for Meaning in the Age of Science.