Yesterday I went to my aunt’s funeral. She was my father’s older sister. Long before he died we lost touch with her and my uncle and their sons. Small misunderstandings arose and then they became bigger, until decades had wedged themselves between our families. She had two boys. Every summer, I had begged them to let me play cricket with them. They never said yes, though sometimes they let my brothers play.

At her funeral I saw her two sons again—now men—sitting with bowed heads by her body. From the other guests, I heard that the doctors had said a clot had traveled from her lung all the way to her heart, stopping the flow of blood. Her oldest son was fifty-four now. I had never met his children though I think one of them was the young teenage girl carrying cups of tea back and forth from the kitchen, occasionally bending to receive pats on the back from visiting mourners. My cousins rose to greet me and my mother, and for a second we were all bemused. My mother held my dead aunt’s sons—my cousins—and cried. I occasionally sniffed but wasn’t able to summon tears. Both cousins had grown up handsome, tall with strong jawlines, their mother’s lips trembling on their faces.

*

I had been told my aunt did not like my mother; that had been the root cause of my father’s fight with his sister, and so I examined my mother too, who was small in the room, the corners of her mouth turned down. I wondered if my cousins thought my mother was dramatic as she cried, after all, she had not seen them in years. Perhaps she was sad for herself, or sad in the way people are when they realize the end is coming and all the people they have known in their lives are marching in a line toward the edge of the cliff, falling off one by one. The smell of rice cooking wafted through the house. We had also heard that my aunt had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. During the last two years she had forgotten how to eat, and so there had been a tube in her stomach through which they fed her mush three times a day. She had even forgotten how to talk. Another thing we heard: many years ago, when her older son married and brought his wife home, she had made the woman stand and pray in the center of the room in her wedding clothes and loudly criticized her form until the new bride burst into tears.

Yesterday, on the way to the funeral, my mother had said, God never forgives some things, and I wondered if she was thinking about this story. But this daughter-in-law, now wedded for many years to the older son, was at the funeral, fine lines around her mouth, holding a boy to her side. Maybe he was seven or eight. Even the woman’s mother, the boy’s grandmother, was there, and the three of them looked like carbon copies of one another as they spoke in low voices among the other guests.

My aunt’s husband, my uncle, was old, almost eighty-seven, and was beginning to forget things too. While I stood in the room trying to pay my condolences to him, another man moved in front of me to say, We are so sorry for your loss, may Allah grant her Jannah.

And my uncle replied, Oh she was so young, only fifty-seven.

The other man said loudly, She was eighty-five. He had the air of a man who was compelled to restore order, and I was grateful. I felt afraid suddenly that I would leave here with the number fifty-seven lodged in my brain and later, when my mother died, my mind would trick me into comforting myself by thinking, Oh at least she lived longer than my aunt.

No, no, my uncle said. She was fifty-seven.

The other man replied firmly, She was eighty-five.

Finally my uncle looked around the room and, spotting me, asked, Are you eighty-five?

At this my cousins rose from the body’s side and said, Abu, come with us, and led him out of the room. When we were kids, the younger one used to eat mayonnaise out of jars because everyone thought it was funny. At mealtimes whenever we were together, his mother would hand him a jar of mayonnaise after he had eaten his meal and he would open it, dip his finger in, and lick it clean while we all laughed and his mother shook her head as if she did not know what to do with him.

This aunt had not come to the funeral for my father, her own brother. We later heard she was telling people that she had not gone because she knew my mother would not let her in, though she should not have worried—all that day my mother had been preoccupied, glancing at the corners of the living room where we were receiving mourners. My father, in his last days, had started dictating wishes for his burial and the wake. Now she wanted to remember exactly how he’d phrased each wish. She thought the people who had come to pay their respects somehow knew that she was in the process of forgetting. Weeks later she kept asking me, Did so-and-so say anything?

Now my younger cousin came back to where I was standing and spoke to me in a low voice. What are you doing these days? I had heard he was not married. I was surprised to note he had a thin, plaintive voice. I told him I wasn’t doing much, as if we were old friends and we were just catching up after a week of not speaking. He nodded and looked around, distracted.

She jumped off the roof, he said.

Startled, I looked over my shoulder as if she had jumped off the roof simply to reappear behind me. She couldn’t walk, I reminded him gently, wondering if grief had addled his brain. She could, he said. He spoke a little louder than he had intended. People turned to look at us. He smiled at my forehead, as if to reassure the room that things were okay. Then he looked directly at me and said, Anyway, what would you know?

She jumped off the roof, I repeated. He nodded, patted my shoulder. It’s good to tell someone that, he said. His chin trembled.

In the other room, my uncle was loudly saying to everyone who would listen, I keep telling everyone she was fifty-seven, maybe fifty-eight, and I could hear loud hmms of agreement.

My cousin moved away and I peeked into the room my uncle was speaking in. When my aunt was still alive, someone must have taken care of the couple, reminded him to take his medicine, bathed and fed my aunt when she forgot to do it herself. I saw people exchanging looks as if my aunt had been the one keeping the whole family together and now that she was dead, they were witnessing its impending dissolution in real time. What will happen to this old man now?

*

I tried to think of ways to love her. I remembered that when I was a child, we had all been watching TV and she had changed the channel when a commercial for sanitary napkins had come on. Then she looked at my mother and said, When we were young, this never would have been on TV, and when I asked her what that meant, she laughed. I imagined her laughing, flying off the roof on a sanitary napkin, yelling, Look how times have changed!

My other cousin, the older one, came up behind me and said, Actually Junaid wasn’t feeling that well when he said that. And minds sometimes go where you don’t want them to. I couldn’t tell if he was talking about his brother’s mind or his mother’s mind or his own. I looked back to see where my younger cousin was standing in the corner. The two brothers exchanged a look I couldn’t decipher.

Of course, I said.

When I thought of my own brothers, who lived far away and were married, I wanted to always love them. Sometimes when they called after weeks of not calling, I picked up the phone anyway to talk to them because I remembered how when my father was dying, you could see in the way his body was becoming just some bones that he wanted to be held together by people who had known the shape of him as a child.

After my older cousin walked away to greet some guests, Junaid motioned for me to follow him. He led me to the kitchen where a cook was stirring a big spoon into a pot. Chicken? the cook murmured as I passed, and I shook my head. A door from the kitchen led onto the lawn. From there, Junaid and I walked out to the main gate. He walked me all the way around the wall bordering the house until we were facing the back of the house.

*

It was all dirt. He pointed to the ground, where you could see a small patch. It looked maroon, like it could have been sheep blood, or goat blood, or almost black, like water from sewers had hardened and crusted there. This is where she landed, he said. He looked directly at me. As one, we looked at the roof. I began to believe it.

I just couldn’t take it anymore, he said. How did she—?

I helped.

You lifted her over the railing? Yes.

I wondered then if he could kill me too. As if he could read my mind, he quietly said, I just needed someone to know who had known her when she was in her right mind.

I nodded.

He let out a low laugh. I loved her but she could be mean sometimes.

I thought of the jars of mayonnaise and his strained smile as he licked his little fingers clean, and I nodded again.

I’m sorry about your father, he said.

He wanted to live, I said. I wanted him to know there was a difference between our parents. When nearing the end, my father had begun to celebrate small achievements, like being able to walk on certain days. But still he had succumbed to death quietly, the only obvious sign of objection the deep, rattling breaths he took on his final day that clanged in my skull for weeks after we buried him. What was the difference between them now that they were both dead?

As if he understood, Junaid nodded. She asked me to do it.

She was so sick.

*

With my foot I scuffed the dirt and moved it around. The color began to disappear.

You’re okay, I replied, as if saying the words would put him back together. I remembered then that I had said those words to my father when he was in the hospital and needed blood drawn, needed a new test, got some bad news. I realized now that I missed saying those words, that I wanted to repeat them forever to everyone I had ever known. I was afraid I would grow old and not know anyone willing to say them back to me.

Yes, he replied, I’m okay. Can I call you sometimes?

Before I could agree, we began to hear people calling his name in the house so we made our way back inside. His older brother glared at us as we entered.

The men picked up the body to carry it outside and eventually to the graveyard. Junaid started to make a loud keening sound as soon as they lifted her. She jumped, he said loudly. She really, really jumped. I helped her, he said. I dropped her in one go. Everyone shushed him as they carried the body out the door. You could tell they wanted to bury her quickly, smooth the earth over this whole day so everyone could go back to their routines. Under the ground there was my father and soon my aunt and one day it would be this son, who was wailing loudly as he got into the ambulance with the body, I pulled the tube out of her stomach and lifted her! Everyone shook their heads. Those boys really loved their mother, I heard a woman whisper to another woman.

After the men took my aunt’s body to the graveyard, I finally went and sat in the big lounge where all the women were sitting. My mother was already there and she made space for me next to her and for just one moment I felt like I had when I was a child and wanted to be near her all the time. I looked around the room, at all the people and distant relatives my aunt had collected in her lifetime. It surprised me that she had continued to deserve and receive generosity from people even during all those years we were estranged. My father used to say, The point of life is to collect people to come to your funeral. These people would not come to my mother’s funeral.

There was an older woman there and she was snoring on the sofa. I took off my shoes and put my handbag to the side. My mother and I began to read from the Quran. My aunt’s grandchildren came in and out of the room, and the women spoke in low voices about their daily lives. Some of them knew my name even though I had never seen them before. They said, How are you? Good, I replied.

Suddenly I was very exhausted. Like the old woman on the sofa, I just wanted to sleep. The men began to come back. They looked tired, and their shoes were caked in dust from where they had stood around the grave when my aunt’s body was lowered into it. Junaid was quiet now. He came in and went straight upstairs to his room. I knew then that I would never see him again.

Every year, my aunt’s family had visited or we had visited them during the long summer holidays in June, July, and August. My brothers and our two cousins and I had spent the days jostling for space on a sofa while playing Nintendo, only stopping for food. For dessert we kept blocks of ice cream in the freezer. They came packaged in long rectangles of cardboard. If we left the ice cream sitting out too long, it would begin to leak out of the cardboard’s edges. My mother would bring an ice cream block out after every meal, and all of us would watch as she quickly used a knife to cut the smooth rectangle into even pieces for us. We held out our bowls where she dropped our share in. After that, my father and my aunt would begin to argue about what would go best with the ice cream and for a few moments, the rest of us had a feeling that they had forgotten us. Cornflakes, coconut shavings, packets of crisps, french fries. They would put something different into every bowl, and then we would pass them around the table so everyone could vote on what tasted the best. Usually my aunt’s choices of what went best with ice cream won, and then she would beam for the rest of the night. Now I think my father let her win. It was a wonderful thing when she smiled. There are many things we take to our graves just because there is no language for how to recount the experience of having lived through them.

Finally my mother motioned for me to get up; it was time for us to go home. From the window, I could see it was a new moon that night, a lovely spring evening. I moved my foot absently as if to find my shoe. It touched leather and I looked down and saw I had put my foot into my handbag. I glanced around quickly to make sure that no one was watching, but the old woman was awake now and she was watching. What an idiot, she said loudly, and then she began to laugh. It took only a second for everyone to see what she was laughing at, and then suddenly the room was alight with laughter. I was prepared to feel hurt but it felt gentle and edifying; that whole evening I had felt like I was walking on something fragile and finally that thing had broken, and now my mother and I were falling through air. All our relatives, all these people we had not seen for years, held us aloft for a bit as they must have done when my parents were younger and when I was a child, and then finally the laughter died, and we were on our way.

__________________________________

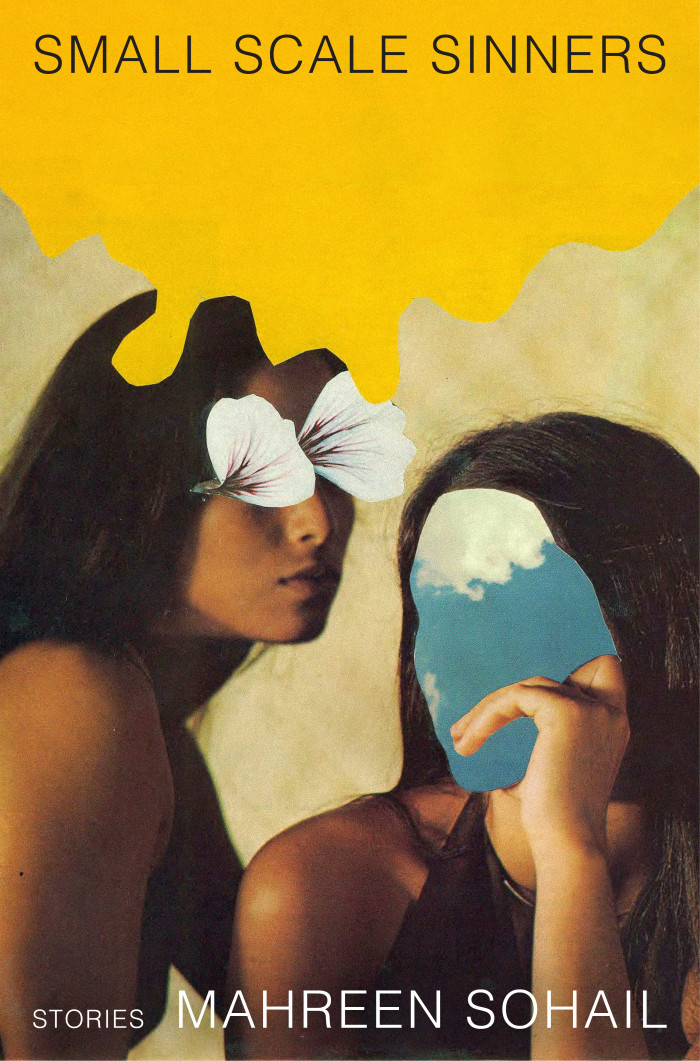

From Small Scale Sinners by Mahreen Sohail. Used with permission of the publisher, A Public Space Books. Copyright © 2025 by Mahreen Sohail.