The Fairfield Day Academy campus was just a big, ranch-style house discreetly set in a quiet residential neighborhood. The treatment was new and Blue Cross didn’t cover it. Except for the office secretary, Dr. Bob was the only full-time person on staff. Speech and physical therapists came in and out but most of the mothers volunteered one day a week. As Dr. Bob liked to say, they had less to unlearn than the professionals.

Emma met all kinds of moms at the academy—a Black woman and her son formerly diagnosed with Down’s syndrome from inner-city Bridgeport; a white Smith College graduate from Westport and her daughter who’d been diagnosed mentally retarded. The only differences that mattered between them had to do with the kids and how they responded to therapy. The living room had been turned into an occupational therapy gym with monkey bars, weights, mats, balls, and patterning tables. Every morning a small team of moms helped the kids through a circuit that started with patterning therapy and ended up in the Listening Circle, where they listened to records of birdsong and thunder. As Dr. Bob said, by learning to hear and identify sounds, the kids were unlocking the part of the brain that controlled speech and language.

*

Emma knew right away that the treatment was good for Carla. Dr. Bob was the first medical authority to even believe there were things to be done that could help her. Just getting her there three days a week in a place with other children seemed to make a difference. Carla’s mobility was already good—they just had to work on her verbal ability. Dr. Bob pushed her toward music and soon she was playing xylophone songs for the kids in the Listening Circle, and even composing them. At nearly four years old, Carla still refused to speak, but Emma was sure she was absorbing everything.

Emma’s volunteer work gave them a partial tuition reduction. To cover the rest, she addressed envelopes, two cents apiece, on a big typewriter Jasper brought home from the office. But that still wasn’t enough. They took out a second mortgage and borrowed again from the Faimans.

On Carla’s Fairfield days, Catherine came home with a house key that she wore around her neck underneath her shirts and dresses. At eight years old, she was sensible and independent. She was careful not to lose the key, careful not to ever show it to the other kids or teachers. Emma worried sometimes that she was letting Catherine grow up wild, but what was the alternative? If the treatments failed, if Carla couldn’t overcome her developmental delays, she’d ultimately become Catherine’s responsibility.

Catherine couldn’t stand to look at Carla. She didn’t like to think about her sister much because when she did, she was overwhelmed with hatred. Her parents and the Fairfield people said over and over, There’s nothing wrong with Carla, she’s just different, but this was obviously untrue. You treat your sister like a vegetable, the visiting therapist chided her at Fairfield. She’d been trying, then, to hide the hate the way she hid the key. Because Carla was a little monster: squalling, screaming, and rocking; blowing air through her lips as if she were farting and then flicking her tongue with a small secret grin. Carla knew exactly how to annoy people. The cries and coos Lydia and all the other Fairfield mothers made around her little sister made Catherine sick. Carla’s head seemed too big for her body, she had wide saucer eyes and thick bushy brows, and it looked like half her face was forehead.

She knew the other kids all knew that Carla was retarded. Her friend Margit told her this as if it was a secret, but it was a secret she already knew. Whenever Emma forced Catherine to take Carla with her to the beach and they passed by the Muller house, the Muller kids all shouted Retard, retard! But Carla did not, could not, react, and so they changed their taunts to Catherine Greene, hey, Catherine Greenberg, your sister is a retard! What’s for dinner at your house tonight, retard-burgers? Catherine’s face turned red. She didn’t know what she thought about the Mullers, a big Catholic Laurel Beach family whose older daughters went to private school at Laurelton Hall, but suddenly the few dozen yards between Wildemere and Laurel Beach was turned into a stage and she was trapped within a spotlight. She wished she could be teleported out of Milford without any of her family.

Hoping to appease her older daughter’s abandonment and rage, Emma let Catherine keep the stray black cat she found next door at the Catalanos’. Jasper hated cats, he disliked animals in general, but when Catherine tried to call her new pet Blackie he became interested enough to help her name it. Wasn’t the name Blackie a little too pedestrian for this extraordinary feline? Not to mention racially insensitive? She should try the French, Noir, it was more elegant. Two days later, Jasper came up with an even better name: Trismegistus. Hermes Trismegistus was the god of the occult and magic, worshipped by the ancient Greeks in the Ptolemaic Kingdom. Jasper took out volume 2 of The Cambridge Ancient History and read out loud to Catherine about black magic and the emerald tablets. What is below is like that which is above. And what is above is like that which is below, she repeated. Were they casting spells? Her mother knew enough to leave the two of them alone when they were working. Sometimes Catherine felt her looking at them strangely. But then the young cat disappeared before anyone could learn his name and Catherine soon forgot about him.

Catherine knew her father was preparing her for a better life beyond Milford. He taught her how to swim in water far above her head and how to ride a bike by taking off the training wheels before she knew what he was doing. He told her stories about the New York Times arts columnist he’d briefly dated and Catherine pictured the apartment that she’d have, two rooms in the East Seventies or Eighties, a big leafy tree outside the window. On weekends, when her friend Bonnie or Margit came over, Jasper led them in a game of Spelling Bee. Each girl moved up one step on the staircase for every word she spelled correctly. He made sure to give her friends the easy words. Catherine, spell “dissolution,” he’d intone, and then his eyes met hers with just the slightest trace of a smile when he asked her girlfriends to spell “dog” and “ball” and “car.” “Milford” was like a private joke between them.

*

When she was five years old, eighteen months after entering Fairfield Day Academy, Carla finally started speaking. Not baby talk: whole sentences. Emma was washing dishes, looking out the kitchen window at another bleak late-winter day, when Carla came up and tugged her dress and said, I’m tired of watching TV, can we go outside? Emma looked at her, then picked her up and spun around the kitchen. From that day on it was as if Carla had always had the gift of speech, just like any other child, but for reasons of her own, she’d decided to refrain from talking. At first she couldn’t fully shape the words. Her speech erupted in a torrent of frustration, too powerful to be contained by the building blocks of language. She howled and gurgled. Jasper thought that she could overcome her speech impediment by putting pebbles in her mouth and speaking to the waves of the Long Island Sound, like the philosopher Demosthenes, but Dr. Bob referred them to a speech therapist in Bridgeport. If things went well, Carla could begin first grade next fall in Milford.

For Valentine’s Day that year, Emma baked a heart-shaped yellow cake, frosted with an egg-white icing that she dyed pale pink and then decorated with a heart made out of Red Hot candies. Why was she still so depressed? She had every reason to be happy: a house, a loving husband, two normal, growing daughters. She missed the first years of her marriage in the Bronx, the way that Jasper sat beside her on the bed and read her stories when she was sick during her pregnancies. Except for church, there was hardly anything they did together. Jasper had so much responsibility at Cambridge, and he’d recently taken a Saturday job at a downtown jewelry store one town over to help pay back the Faimans. He refused to work at the new Milford mall where everybody went. What if someone from their church saw him?

The cake looked almost like the picture in the magazine and Emma was pleased with it. She’d put on so much weight the last few years. She had to learn to be more sociable and outgoing.

*

As a young adult Catherine struggled to remember anything about her Milford childhood. There were the Sunday drives, she guessed—her father at the wheel, her mother struggling to turn the aimless drive into an outing—and there were picnics, hikes, the mall. Dunkin’ Donuts, Mister Softee, trips to Bridgeport with her sister and her mother, a shabby zoo or a museum. There were the games that everybody played one spring, or maybe several springs, in the big dirt yard next to the Tiermans’. It’s getting late. The games went on through dusk until everyone went home for dinner.

Catherine walked home alone from school beginning in first grade. She liked cutting through the marshy woods that started near the school and circled all the way to Milford Point, behind the houses. A cutoff from the main path took her almost home, to a vacant lot near the Shaminski’s. Walking home one winter day in second grade, she saw a gang of boys ahead, running through the woods with sticks and branches. She felt a jolt of panic. As she approached they formed a human chain and blocked the path. Jimmy Shaminski looked at her and laughed. Now you’ve got to pay a toll, he said. They linked their arms and wouldn’t let her pass. A toll? She was confused, she couldn’t figure what they wanted. Jimmy was the leader but what scared her most was seeing all the other boys, boys she thought she knew, transformed into bullies, delirious with power.

Until now Catherine had stayed underneath the radar at Kay Avenue School. She wasn’t popular like Pam Miller or Janice Romano, but neither was she ostracized like Deirdre “Grimy” Grimes or Fatty Patty. Catherine thought: if she ran back to school they’d chase her, but if she paid they’d make her pay the toll forever. But it was impossible to pay because she’d spent her money in the cafeteria.

Finally she offered them her mittens. They were nothing special, navy blue from the Goodwill or Kresge’s. Jimmy held them up close to her face and spat into them. Then he tossed them down the line of boys to Wesley Hall, who threw in between the cattails in the swamp. And then they ran away and she could not stop weeping. She stopped walking through the woods after that, told no one.

Third grade was a reprieve, an oasis of happiness, due to the arrival of Susanne McCoy, the only child of a literature professor from Bloomington, Indiana. Dr. McCoy was on sabbatical, researching his next book at Yale, and they’d rented an old summer house next to the beach on Naugatuck Avenue. Finally Catherine had someone to talk to! Susanne looked sweet and compliant with her blond, almost waist-length hair, but really she was a tomboy fiend in search of new adventures. The two girls talked nonstop in each other’s bedrooms, they wrote plays and acted out the parts together, they pretended to be Russian spies.

Boris! Susanne would say, holding out both of her arms, and Catherine would faint into her arms and sigh, Natasha! They made friends with a lone radio announcer at a station near the school who let them sit in on his broadcasts. He even let them act out one of their plays on his program.

In June the McCoys went back to Bloomington and Catherine spent the summer moping. Emma tried to cheer her up, enrolling her in a class called Stretch ’n Sew where girls learned to make dresses from synthetic fabrics, but she refused to go. She could not think of anything more tacky or ridiculous. Entering fourth grade that September, Catherine was surprised by how many friendship alliances had formed and shifted. Blinded by her romance with Susanne, she’d virtually ignored her friends Bonnie and Margit and now they’d been recruited into Pam Miller’s friend group. Everybody knew that Pam hated Catherine. Meanwhile, the other Wildemere Beach girls—girls from big blue-collar families whose parents partied on the weekends—had formed a tighter clique that Catherine never would fit into. Once, Catherine passed a note to Bonnie asking, Why does Pam hate me. Instead of writing back, Bonnie gave it to Pam, who passed it on to everyone who mattered.

Pam’s family lived in Laurel Beach. Her father was an architect. Poised and icy, she styled her blond hair into a bubble cut and she wore the most conservative designer outfits. Margit and Bonnie drifted further into Pam’s orbit and decided not to speak to Catherine, which made the lunchroom newly problematic. Everybody knew: the Wildemere Beach kids were afraid of stirring Pam’s wrath, and anyway they had nothing much to say to Catherine, so they shunned her too. Which left just the bad kids’ table—people like Juanita and Debbie, Tiny and Dale, whose families were actually poor and often absent. These kids failed every subject. But Catherine was still getting A’s and they were not her friends yet. There were still the Outcasts—Lee “Needlenose” Nadel, Grimy Grimes, and Fatty Patty—who sat together by default, but Catherine couldn’t bring herself to join them.

Instead, she left. Every day at lunch she slipped out the kindergarten entrance and over to Bill’s Diner, a quarter mile from school just past the Naugatuck Four Corners. Her lunch money paid for a hamburger and Coke and she sat at the counter, reading the morning paper alongside commercial travelers and truckers. No one there knew who she was. She liked to think that she could pass as an adult. At times like these she could relax, she was no longer lonely.

__________________________________

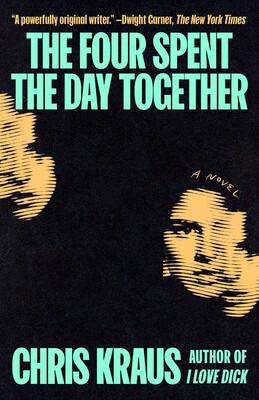

From The Four Spent the Day Together by Chris Kraus. Copyright © 2025 Reprinted by permission of Scribner, an Imprint of Simon & Schuster, LLC.