The four humors that pump through my body determine my character, temperament, mood. Blood, phlegm, black bile, and choler. The excess or lack of these bodily fluids designates how a person should be.

I don’t know what choler means, and when I google it, the internet leads me to a link asking whether choler is a Scrabble word. What is choler? asks Cooper when I report my findings. We’re at my grandmother’s, where she is resting. She is tired from shopping for bargains on towels all day. The window’s open and a breeze moves through the apartment, carrying cat, gull, and car sounds from the street into the room. Because my grandmother is napping, Cooper and I can lounge on her sofa together and even touch arms. We search bodily fluids online, and Hippocrates, who first worked this theory out. Hippocrates was born in Kos, a Greek island off the coast of Turkey, and Cooper and I soon learn that humorism was practiced primarily in this geographical region and became very popular in the Islamic golden age. Cooper and I have been in Istanbul for two weeks now. We’re here for the summer. Me, to take care of my grandmother and to see my father’s grave. Him, to see that I do these things.

Before we came to Turkey, my mother set some ground rules. I would stay at my grandmother’s apartment in Levent, and Cooper would rent a room two neighborhoods over, at the top of Bebek’s hill. No sharing a bed. No kissing in public, because the real Turks won’t do that openly. We kiss, instead, when we are alone in the room Cooper is renting near the eye hospital, where he’s working. I was supposed to volunteer at a hospital, too, until my headaches began.

Choler, it turns out, is yellow bile, and in excess can compel even the most calm and gentle person into a hot-tempered rage. Phlegm makes you sleepy and sluggish, but you are also known for your dependable nature. Black bile is melancholy, and blood is the best humor. Blood pumps you into a kind and optimistic person.

Wow, says Cooper. He hovers his finger over my computer screen to point out a warning that too much optimism can make you insensitive to those around you, apathetic even. We agree that many people suffer from this blood condition. We agree that although this topic is interesting, it may not explain my headaches. And we agree that my grandmother’s Parkinson’s cannot be explained away as phlegm.

The humors theory prevailed until the nineteenth century, when another man discovered germs: Louis Pasteur, who laid the framework for medical sterility and sanitation. But I believe in fluids more than germs, even though I am supposed to become a doctor. They say that Saint Margaret Mary Alacoque, who was visited by Christ in a yearlong string of revelations in the 1670s, suffered from an excess of blood. She was his chosen instrument, Saint Margaret said, but she could not convince others to believe her. Christ asked her to initiate the feast of the Sacred Heart. Christ permitted her to lay her head on his radiant, torn-up chest. To cure her delusions, the priests decided to bleed her out once a month. They would cut her white thigh and have her sit in a stone basin. But my understanding of Christianity is limited and mostly googled. I am unsure what they did with her blood.

We’ve come back to the outdoor market because last week we couldn’t decide on the right towel to buy for Cooper’s family in California. The first time we pointed at towels and we touched them. We discussed absorbency. We shared our preferences on which pastel colors we believed to be the best pastel colors. We left the market with nothing.

It’s crowded today and we’re having trouble wedging through everyone. I think Cooper wants to be polite. He hates mowing people down. I take his hand and weave through women weighing fruit in their hands and children begging mothers for plastic toys but I step on the tail of a street cat and it snarls up at me, baring a mouthful of tiny white daggers.

Cooper wants this purchase to be perfect. We wave dozens of towels out and the shopkeeper has me wrap my handsome American husband, she calls him, in a big blue one to test the soft cotton, before Cooper finally settles on purchasing three towels.

Last winter, I invited Cooper to follow me to Istanbul for the summer. Then we coined it our adventure, and by spring, he found a job at the eye hospital near the university. He’s a curious person and renowned among our friends for being kind. Like me, he thinks there are vast pools and caves of phenomena that cannot be explained by science, and he frequently admits his regret for having been raised without a religion. I summon and repeat the words our adventure in my head, an incantation, until the letters press against each other with so much speed and force they blur and break and I’m left here, in this market, on no adventure at all, only a mixture of mutated letters in my head and a plastic bag of towels in my hand.

We decide to take the bus to a café near the eye hospital because Cooper has two hours before he has to head into work. The bus windows are open and a breeze moves through. We take turns leaning against the pole because Cooper has given our seats to a woman with two children. Here, he’d said, gesturing, his smile as wide as an ocean across his face. They scrambled into the seats, and me, I got up, trying to be as kind as him.

He pulls out his towels from the plastic bag and holds up his purchases. I’ll give my mom these two blue towels, he says, and my sister this purple one. What do you think?

I say, I think that’s great. They will definitely love them. I am convinced of this because my family loves them, these thin towels. They are much more absorbent than people think.

Should I have bought my sister two towels, too? Do you think it’s fair that she gets one but my mom gets two?

The light pours into the bus and we sway on its pole as it swerves through the hills. A city becomes hilled due to an eternity of earthquakes, and scientists predict that Istanbul will experience its next fatal earthquake sometime in the next ten years. The two children have their small hands in their laps and stare up at Cooper as if in a trance, and he beams back. My head has ached since May, more or less the same amount of time I’ve been in Istanbul. My brain is an earthquake or an ocean. Whichever I am more likely to survive.

_______________________________________

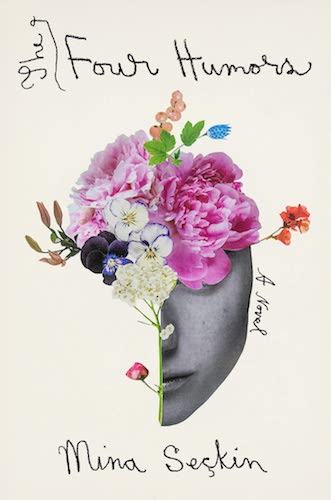

Excerpted from The Four Humors by Mina Seckin. Copyright © 2021 by Mina Seckin. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.