Two people were walking towards me last night, their conversation hissed and urgent. As they grew closer, I heard one say, “Listen, you just pick up the phone and tell him, ‘Lewis. Your fish tank crab has escaped!’”

Then they turned and rushed off into the city, deep in their panicked logistics. This was, without a doubt, the best thing I’d ever overheard. I was thrilled—the narrative possibilities! In my brain, a web of neurons immediately flickered:

Oh, Lewis! What news to receive during your holiday in, let’s say, Mauritius, where you are snorkelling to commune with sand sharks. When you are told that your fish tank crab has escaped, you’ll recall how you, as you put it, “rescued” him from between some loose foreign rocks years ago. The crab, let’s call him ‘Ramon’, was red as a Chevy and fast as one too, but you, Lewis, were faster.

Ramon did not take well to his rescue. Back at your flat in London, he wouldn’t mix with the fish, eels, and assorted ganglia in the large tank. He did not even acknowledge the one-eyed octopus, who was anyway soon moved into a tank of her own because she was, as you later explained to your neighbour, “prone to warfare”. Instead, Ramon burrowed deep under the plastic stones at the floor of the tank until one almost became lodged in his shell. The crustacean Gregor Samsa. You had to jimmy it out with a fish knife as carefully as possible because Ramon was always poised to pinch. Such an opportunist, you chuckled, dropping him back into the tank.

I’m sorry to report that when you left for your holiday, Ramon saw his chance. You had asked your neighbour, let’s call her “Jess”, to supervise the tanks during your absence. “Would you overSEA my aquarium?” you had texted her, proud of yourself. Let’s be honest, Lewis, you had more in mind than just temporary custodianship of the fish. You had hoped that this might be the start of something between the two of you. You thought that Jess would be so impressed by your huge tanks that, on your return, she’d maybe greet you warmly, with a welcome home dinner and a freshly cleaned apartment. Or something. You did not realise that the woman who seemed to share Jess’ place, let’s call her “Keisha”, was in fact her girlfriend. You’d assumed that they were flatmates with separate rooms. Still, you had warned Jess not to bring anyone else into your flat while she was there. “It’ll compromise the safety of the tanks,” you’d said. “One wrong move – maybe he slips, maybe he rests his arm on a filter and bam! Disaster. Better just come in yourself.” The truth was, Lewis, that you wanted to establish the sort of intimacy that only comes from separation. You took such good care of your carefully chosen fish, you thought. Jess would surely see the beauty in your selection and protection, and perhaps wish to be so selected and protected herself. Or whatever. “Just you,” you’d repeated.

Jess had agreed to feed the fish during your time sunning at the beach, your body soft and white as the flesh under Ramon’s carapace. You’d explained that she should come in, shake a few flakes into the top of the tank and watch as the fish made kissy faces in acceptance. This is what you had always liked best about your tanks, Lewis – the romance of supplication. Whenever you’d fed the fish, your fish, you felt like a member of the Peace Corps, bearing alms. A benevolent god.

Jess was not a benevolent god, she worked in Sales. She also believed that you should always be on good terms with your neighbours just in case. To be honest, she was more of a dog person but thought that fish wouldn’t be too difficult to handle. “They’re low maintenance,” she’d reassured Keisha, worried that she’d be irritated by this new addition to the many chores that seemed to make up domesticity. But still, Keisha came with Jess to feed the fish.

The escape happened during their second visit to your flat. Jess and Keisha had laughed the day before, when they went into the small, sad studio. This was important – it had been the first time that they’d laughed together for three months and they’d only been together for four months. The flat was flanked by your two enormous fish tanks, but there was basically nothing else in it – a fridge, a leaky waterbed, and a long, rusty lamp. But they did admit that the tanks, filled with all sorts of weird creatures, were pretty cool. Although, as Keisha noted, “Not on, like, an aquarium level.” Jess had thought this was a bit petty (who could fit a whole aquarium into a studio flat in Crystal Palace?), but she didn’t say anything, not wanting to ruin the sudden easiness between them.

Jess and Keisha had met via a dating app. At first, Jess had found herself left-swiping a deluge of dudes before she figured out how to change her settings to women only. This didn’t quite sum up Jess’ preferences though, but at least this way she wouldn’t have to deal with gross men. Except, of course, she did. After five right swipes that led to unsolicited dick pics clogging up her inbox, hard and crusty as a coral reef, Jess had connected with Keisha.

Keisha helped build film sets, had a knuckle tattoo, and all of her friends wore tight jeans and baseball caps. Jess liked to read fantasy novels and go to movies with her co-worker and best friend, Mac. Keisha was a serial monogamist who had never had a one-night stand. Jess had never been in a serious relationship and felt it was time to try one out.

On the day of Ramon’s escape, she and Keisha were probably on the verge of moving in together. Keisha spent every night at Jess’ and her PlayStation was always connected to the TV, so Jess assumed that a shared lease was on its way. This must be love, she thought, doing everything together. Like, everything – pub crawls, grocery shopping, keeping the bathroom door open, everything. Which was fine, Jess supposed. Except, as she’d explained to Mac, she had begun to suspect that there was something low burning under this shared time, a feeling of deep and unspoken resentment that Jess could not understand. She didn’t particularly want to shit in full view of Keisha, but it was clear to her that to close the door would be unforgivable. “Lesbian subsummation” is the term Mac used, which Jess took offense to, because she did not feel completely lesbian nor subsumed. But she understood Mac’s frustration – outside of work, Jess barely saw them anymore and this was because of Keisha. Whenever Mac texted Jess to hang out, Keisha always had some event or errand that she expected Jess to be present at instead. Or, worse, Keisha was insulted that Mac hadn’t explicitly invited her along too, even though she didn’t seem to like Mac and wouldn’t stop misgendering them. And so, Jess would decline Mac’s offer in front of Keisha, but then meet them for lunch during the workdays, wincing as they made fun of Keisha’s plans to go camping over the next bank holiday. Jess, who passionately hated nature, would of course have to go with. But that was love, Jess explained. “What?” Mac had asked. “Being microchipped?” She ignored them.

Jess followed your painstaking instructions, Lewis, first clearing any old debris from the tank with a little net. Keisha was talking about something when Jess spotted what looked like a piece of red plastic peeking from beneath a castle. She used the net to try to dislodge and free the scrap. But it wasn’t a scrap. It was Ramon. He dove at the net, a dinghy in the darkness, a sudden bridge to freedom. Jess watched, shocked, as a crab she hadn’t even known existed scuttled up the handle, onto the tank’s rim, and then stopped. He and Jess sized each other up. Ramon was small, but quick and decisive. Jess was larger but required time to weigh up her options before acting. She tried to imagine what she would want if her own hypothetical pet – in her imagination, a Saint Bernard – escaped while in Lewis’ care. She would want the Saint Bernard retrieved, she decided. So, Jess tried to grab the crab, but Ramon would not be twice snatched. He leapt right into the face of danger, landing square on her nose, and pinched.

Jess’ screams interrupted Keisha’s description of the new cycling club she had recently joined, an all-women group that met in a small workshop in East Croydon. “What the fuck?!” she yelped when she saw Jess flailing around with a crustacean attached to her face. Ramon, his sight now partially blocked by Jess’ hair, spotted the front door that had been left ajar, and launched towards it. This sudden movement sent Jess reeling backwards and almost into the main fish tank, but Keisha grabbed her arm, pulling her away just in time. They stared at each other. Imagine the cost of replacing the tank! Jess shuddered to consider it. You had always seemed a bit litigious to her, Lewis, although Jess didn’t know how much expendable income you had to pursue legal action. But she did not care to find out.

On their first date, Jess and Keisha had split the bill for their meal and paid separately for their drinks at the bar they’d moved on to. This had been familiar to Jess, who always paid for herself. But, as the relationship progressed, the rituals around payment became indecipherable to her. Sometimes it seemed to Jess that they should, of course, pay separately. But then, at other times, she wondered when the point of merging finances might arrive? For example, was it fair to ask Keisha, who stayed over every night, to help with the rent? Or perhaps the utilities, since she clearly had a deep aversion to switching off lights? But then, at the same time, something in Jess bristled whenever Keisha moved to pay for them both. Jess did not want the teller at the Sainsbury’s to assume that she was a kept woman. But then, after a few passive aggressive discussions that resulted in them buying separate groceries, Jess worried about that too. Did the teller now think that they were only flatmates? How, Jess wondered, had they crossed so silently into cohabitation while still filling out Excel spreadsheets independently, almost secretly, after each pay cheque? Was intimacy being in such close proximity to someone that you knew by heart the smell of their trainers, or the different meanings of their sighs, but had no clarity around their overdraft?

Back at your flat, Ramon was now darting beneath Keisha and Jess, leaving small sploshes of water in his wake. Trying to avoid him, Keisha hopped over the crab and slipped. Now it was Jess’ turn to grab her, but she didn’t make it in time. Jess watched as Keisha fell sideways into the second tank, the tank that you, Lewis, had warned her about. The octopus tank. It was, as Jess would later explain to Mac on the street where I encountered them, a true cluster fuck. The tank slowly tipped over and then made impact with Keisha’s head before it hit the floor. It cracked open, sending small pieces of glass and a large, dark octopus loose. This tank had not contained the same paraphernalia as the first one, no castles, no pebbles, because, you’d explained, the octopus – let’s call her “Maureen” – had a history of using secondary objects for “nefarious purposes”. Jess had laughed then but she wasn’t laughing now. This meant that the second tank had just been a glass box, dark and tightly sealed, in which Maureen waited. But now she was free.

“Close the door!” Jess hissed at a bruised Keisha, who slammed it shut just before Ramon reached it. Maureen had not moved. Everyone else in the room – Jess, Keisha, Ramon – watched her. Even the other fish, safe and dispassionate in the first tank, watched the octopus. But Maureen kept her one eye tightly shut, giving off the air of a former assassin about to be forced out of retirement by bungling younger criminals. Ramon, who knew any noise he made might alert Maureen to his presence, stayed perfectly still. Jess and Keisha stared at each other in horror. An octopus and a crab were at large in the kitchen, which was now full of pieces of glass and tank water! What a fucking mess. They made intense, silent gestures to each other to confirm a plan of action: Jess, who was nearest Maureen, would try to grab and deposit her in the first fish tank; Keisha, now closer to Ramon, would wrangle the crab. They both suddenly realised that this was the only time that they’d had a conversation, a real conversation that wasn’t about bikes or groceries, in weeks. Their semaphores became intimate, loving. They smiled at each other.

Their second date, Keisha remembered, was at a party in her friend Claire’s garage. A band was playing battered instruments, harmonising and screaming at the same time. Keisha and her friends were dancing manically near the stage, although perhaps ‘dancing’ was the wrong word for it. As Jess would tell Mac the next day, it was more of an ironic mosh pit. They would bash their bodies together, flannel and denim making scratchy contact and emitting small clouds of deodorant.

Jess was at the bar with her Kindle when Keisha went over to her.

“Come dance!” she’d shouted. Jess was shy, Keisha had thought, and it was adorable. “No, I’m good,” Jess had said. “Come onnnnn,” Keisha had pulled at her sleeve until Jess, laughing, joined them. The moshing began again, when a new song blared. Keisha could see Jess sort of getting into it – the pack of people impacting against each other. It was a wonderful camaradarie of the body – sternums and limbs embracing and repelling. In the sports that Keisha watched, there was always a romance between the players, who hurtled against their enemies, who supported and held their teammates. That was that same feeling here, Keisha felt. The closeness of being with your kind, of throwing your body against theirs and knowing it would be caught firmly, pushed firmly, loved hard. Jess had smiled at her. Jess was finally, like, getting it, Keisha’d thought. She slowly chest-bumped Jess, who giggled and nudged her back.

Ramon was too focused on Maureen to notice the urgent signals above him. Jess and Keisha took deep breaths and then lunged. Ramon, suddenly grabbed by soft human hands, pinched at the air without thinking and Maureen heard his clicking pincers before she even felt Jess’s fingers. Her eye flew open. Ramon. With one fell swoop, she slapped Jess’s arm away. Octopus legs, which Jess had only ever known on calamari platters, were suddenly weaponised against her. Another slap. The suctions on Maureen’s tentacle delivered violent hickeys along Jess’ arm.

Lewis, you of all people know what it is to be hit by an octopus. It is like being struck by an alien: electric and clammy and paradigm-shifting. Jess tried to grab Maureen again, but the octopus delivered another wallop, now to the face. Keisha was frozen, watching Jess being assaulted by an octopus. All of her hours of video games and biking had not prepared her for this. She prided herself on being a practical person, but she had never mentally nor physically anticipated such a situation. What must happen?

Keisha had never formally come out to her family, but everyone knew and seemed fine with it, she assumed. It was difficult to tell over the weekly phone calls she made to them on Sundays, when they were all sitting in the lounge during the break between the Sunday roast and Carte Blanche. She’d moved to London from Joburg about ten years ago, after yet another terrible break-up with another complicated girl from university. Since then, Keisha had gone through three more terrible break-ups in London, all with women she’d met at work or the bicycle shop or her ex’s birthday party. And it was always the same story. They would meet, and talk, and fuck, and do everything together. Then they would argue, and cry, and the girl would have an emotional affair with someone they both knew, and then leave. Keisha was sick of it. Her best friend, the first of her London exes, gave her the following advice, which she had taken to heart: “Don’t shit where you eat.” And so, Keisha had gone onto the app and looked for someone she had never seen before. It was there that she found Jess. Jess was cute, she’d thought, although not in the way that Keisha was usually drawn to, but still, definitely cute. And, most importantly, no mutuals. Not a one! This was rare beyond measure in a scene that had proven to be as small and incestuous as the one she’d fled in Joburg.

Four months into the relationship, things were going good, she’d thought. Jess was pretty low-maintenance, which Keisha liked. She was weird but not in an intimidating way, not the kind of weird that expected Keisha to read the same books and watch the same movies or anything. And Jess was always really excited to hang out with Keisha’s friends, where she was the perfect combination of friendly and unintriguing. No one thought that Jess was a downer but none of them would text her unbidden. Perfect. Keisha didn’t even mind doing Jess’ boring errands – going to the library on a Saturday morning, grocery shopping, feeding some weird neighbour’s creepy fish – so she went along without complaint. Without much complaint. It was nice to be in the comforting routine of companionship, the drama-free promise of her thirties. At some point, Keisha realised, they seemed to have moved in together, which was just fine with her because she technically still lived with one of her exes. That is, it was fine with her until today.

While weighing up her options, Keisha accidentally loosened her grip on Ramon, who wriggled free immediately. Maureen took off after him, slithering fast across the floor. Deciding that the crab was the lesser issue, Keisha took off her jersey and managed to wrap it over Maureen while the octopus was distracted. Jess grabbed a side of the jersey and the two of them moved towards the first tank, ready to throw the octopus in. Maureen squirmed with the indignity of being slung around in a cardigan, her tentacles thrashing out of the neckline. Ramon had managed to make his way to the waterbed – above it was an open window to the hallway. He could, he determined, climb up the lamp, onto the sill, into the passage, and then the world. But the women’s shrieks as the octopus thrashed in the jersey stopped him. Maureen was, once again, trapped. Who knows what he thought in that moment, Lewis? Maybe he remembered something about his home? Maybe he imagined something about Marueen’s? Maybe he recalled an incident between the two of them? Perhaps related to her missing eye, perhaps not? Does a crab remember and imagine? I cannot say. Keisha turned to look at the waterbed and saw that Ramon was sitting right in the middle of it. Maureen wobbled and shook beneath Keisha like an awful jelly, her eye poking out a sleeve hole. Seeing it, Ramon raised his pincers, as if in greeting – perhaps a hello, perhaps a farewell. Then he thrust his claws into the bed.

A surge of old liquid flooded the flat. The water was fetid with time and humiliation – so many memories of you, Lewis, after another swift round of masturbation, wiping your hand on the mattress and not looking at the fish, who had already averted their eyes. When the bed burst, the lamp next to it, which was meant to be Ramon’s ladder to the window, was upended. Trying to get the crab with one hand still on the jersey, Jess slipped backwards, bashing into the first tank. The room froze as it teetered slowly, slowly, and then fell. It smashed onto the floor, sending all of the fish flying. Keisha skidded and let go of the jersey, and Maureen, that escape artist, dove into the murky low water like Esther Williams with tentacles. Before she was completely submerged, though, she looked up at Ramon and some understanding passed between them. I won’t pretend to know its meaning, Lewis. If I was a more ambitious writer, maybe I’d try to pin it down by using words like “collusion”, or “intimacy”, or “regret”. But those are my words, not theirs. I cannot speak their language – we lost it when we stopped being animals and started calling ourselves people. Anyway, all that matters is this: whatever it was that passed between them passed, and Maureen sank into the dark water never to be seen again. Who knows what happened to her? Remember that the window was open. Remember that she was prone to warfare. Remember that she had a history of using any object she encountered for her own nefarious purposes.

Keisha, who was perhaps slightly concussed from the crash of the first tank, had had enough. She loved Jess, she guessed, but she hadn’t signed up for this. By trying to escape the usual dating drama, she now found herself literally ankle deep in an even worse kind. And so, Keisha abandoned her relationship to the disgusting depths, and stormed out, leaving Jess behind, shouting at her to stay. What a metaphor, Lewis, to be broken up with in someone else’s flat, surrounded by bad water and emancipated fish. In her hurry, Keisha left the door open and the water rushed out into the hall. And so did Ramon. He let himself be flushed out of the flat, your flat, Lewis, and into the world.

When you return, it will be to this: smashed glass, soaked floorboards, a sink filled with fish, and a landlord who has highlighted the part in your signed lease refusing you the right to keep any pets. Jess will be absolved from legal repercussions as a result, although she’ll soon move somewhere nearer to the British Library and Mac, leaving memories of Keisha and her PlayStation far behind. And you, Lewis, will be alone with the consequences of capture: no deposit, octopus nor crab.

I’m sure most of the details in this story are scientifically incorrect. I’m not an ichthyologist, Lewis, I’m a poet. I wrote this because I too have been kept in tanks by those who thought that to contain me was to appreciate me. And, listen, I’ve done the same to others too. But I have learnt that there’s a difference between trapping and living. An octopus must conduct warfare, a crab must scuttle and pinch, Jess must read, Keisha must ride, I must make up stories, and you – I don’t know what you must do, but it cannot be this. So come home, Lewis. Come home to your warped foundations and your ruptured bed. Come home to your empty tanks and reckon with your choices, with yourself. As we all eventually must.

__________________________________

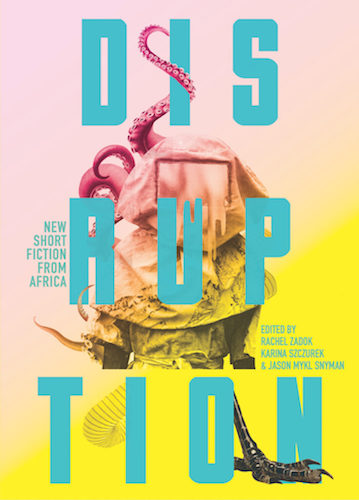

Excerpted from Disruption: New Short Fiction from Africa, edited by Jason Mykl Snyman, Karina Magdalena Szczurek, and Rachel Zadok. Published with permission from Catalyst Press. Copyright (c) 2021 by Genna Gardini.