Perhaps we should start with how Polari should sound. Many speakers had regional accents, of whom a good proportion would have had London, especially East End or Cockney, ones, as London was Polari’s spiritual home. You don’t need a Cockney accent to speak Polari, though—I interviewed speakers with strong Scouse and Glaswegian accents. And Liverpudlian Paul O’Grady, who performed as Lily Savage, knows plenty of Polari.

Speaking in a “posh” upper-class or a middle-class “received pronunciation” accent, sometimes thought of as standard English or what people say when they claim (incorrectly) to have “no accent,” isn’t great for Polari, unless you can also sound very camp. Ideally you should have a regional accent, Cockney if you can get away with it, but then overlay that with the occasional affected attempt to sound as if you’re descended from your actual royalty.

Just as the word queen was used to describe men who often came from modest backgrounds, the accents of these men also had majestic pretensions. Kenneth Williams is a good role model. He grew up above his dad’s hairdresser’s shop, but in his many Carry On film roles he acted with an upper-middle-class provenance, playing a variety of haughty doctors and professors, presenting a slightly stern posh accent when trying to impress, although slipping into Cockney when highly excited.

Kenneth’s Sandy exploits the Cockney accent in the Round the Horne sketches to insert more Polari into the dialogue. In a sketch called “Bona Homes,” where he and Julian play landscape gardeners, he opens with, “Oh hello Mr. Horne, we’re bona ’omes you see.” By dropping the h in homes, he is able to make the word sound more like omee, the Polari word for man.

Or listen to the recordings of Lee Sutton’s drag acts. Compared to Williams, who always sounds animated, Sutton has a deadpan comedic delivery—and although he’s in drag there’s scant attempt to contrive to the audience that he’s female: his voice is unapologetically gravelly. However, he sounds like he is having a good time, and that’s key to Polari. Even if your heart is breaking on the inside, you keep up the act, whether you’re in drag or out of it. A Polari queen never cried, until she got home and drew the curtains.

The “pseudo-posh” bits of Polari can come across in a variety of ways. Some Polari speakers could sound quite cosmopolitan as they threw bits of classroom French (or, less frequently, German) into their conversation. While Polari has a complicated history, picking up all sorts of linguistic influences over the decades, my guess is that use of French was more about showing off than there being a more substantial French connection.

For the average working-class Brit in the 1950s and 60s, holidays “abroad,” as the world beyond the English Channel was known, were much less common than they are now. A bit of French could imply that the speaker was a glamorous jet-setter or at least had a foreign boyfriend. However, I don’t think that most speakers were convincing anyone of this, other than the most naive chicken. Instead, use of classroom French was more parodic, based on the understanding that it is funny to pretend to be someone who thinks that speaking French is glamorous.

Attempts to speak those little bits of French in an actual French accent are therefore to be frowned upon—that would be trying too hard and indicate that the speaker really knew French as opposed to be pretending to know it (although using an exaggerated French pronunciation is acceptable). Julian and Sandy regularly made use of a set of stock French phrases, including artiste, tres passé, intimé, pas de deux, entrepreneur and nouvelle vague. And one of Kenneth Williams’s party pieces was to sing a song called “Ma Crêpe Suzette,” which consisted of a string of unrelated French phrases that have been absorbed into English, put to the tune of “Auld Lang Syne.”

Polari is about drama and Polari speakers were drama queens par excellence.The phrase gardy loo (meaning beware) is derived from the French garder l’eau (beware the water), originally used when the contents of a chamber pot were thrown out of a window onto the street below. Lily Savage has noted that some Polari words also have –ois added to them—such as in nanteois, none, and bevois, drink. This has the effect of making them appear as if they are French, introducing a further level of complexity.

Polari, when spoken naturally, can have an exaggerated intonation style. Vowel sounds can be dragged out and within longer words there can be multiple rises and falls across the different syllables. Take for example fantabulosa, which contains five syllables: fan-tab-u-los-a. If used as an exclamation, as Sandy would sometimes do, the “a” sound in the syllable “tab” would be extended while the following “u” would have a falling intonation. Then the “los” part would have an almost hysterically rising or a rise-fall intonation, along with another lengthened vowel sound, with a final, slight falling intonation on the last syllable, making the speaker appear exhausted but triumphant.

But there are numerous other combinations of rises, falls or accented syllables that can be applied to fantabulosa—try enunciating it in at least three different ways, aiming for the campest intonation you can find!

Exclamations were an essential part of speaking Polari, being associated with “stereotypically feminine” language, as they are reactive. If we say, “oh!” or “really!” or “fabulosa!,” we’re usually reacting to some sort of external event such as someone’s wig falling off or a claim about how many men someone danced with at last night’s ball. There have been claims by some feminist linguists that women carry out what has been memorably described as “shitwork” in conversations, especially with men. This shitwork involves all the little things that people do to keep a conversation running smoothly—asking questions, showing that you’re listening with little “ohs” and “ahas”, choosing topics that you know the other person will want to talk about. It’s very tiring.

Men, on the other hand, aren’t meant to even acknowledge that someone else has spoken—they just stand a little away from everyone, facing the wall in a murderous sulk, or they simply bludgeon their way into an ongoing conversation, interrupting whoever is speaking to tell them they’re wrong (usually on a subject they know nothing about), or to change the subject to sport or cars or politics. If they can get a little boast in about their sexual prowess or how much money they make, then all the better.

That’s the stereotype at least, and while it holds for a small number of men and women, some of the time, actually most of us are pretty versatile communicators and there are more similarities than differences between the sexes. Polari, then, with its exaggerated exclamations and its dears and duckies and empty adjectives (bona!), feels like a hyper-realized version of stereotypical women’s speech—a parody of how women talk taken to a hilarious extreme—a linguistic form of drag.

There are different ways to speak Polari, then, linking through to personas—the piss-elegant posh queen, the world-weary seen-it-all tired old queen, the excited, breathless young queen, the witty, caustic queen, the gossipy queen who knows everyone’s business. Each would use a different set of intonational patterns for different effects.

*

Polari is about drama and Polari speakers were drama queens par excellence. Another feminine stereotype—gossip—is meat and drink to Polari. Polari was essentially a social language, and many speakers lived in densely packed urban areas and had numerous friends, acquaintances, lovers, one-night-stands, exes, crushes, stalkers, rivals, enemies and frenemies. They also had a perfect recollection not only of all of their current relationships but of the status of the relationships of all of the other people that they knew, and social occasions would be spent updating one another on these relationships in great detail.

As a young and introverted man on the gay scene, I often found this volume of gossip to be dizzying and overwhelming. I’d sit in the living rooms of some new friend who’d invited me round and then three or four of his other, more long-standing friends would arrive and there they’d sit all afternoon, drinking cups of tea and talking about all the people they knew, with me a sullen presence in the corner, to the point where I was sure they were simply making up names—nobody could know that many people! There couldn’t be that many people in existence!

Gossip is one of a queen’s weapons—you never know when it’ll come in handy, and much of it is, of course, geared towards the possibility of having sex with someone at some later date. Keeping track of who has split up with who, who is rumored to have been seen down the cottage, who made a clumsy pass at who, whose wig fell off on the dance floor—these are all matters of state importance to Polari speakers.

The large number of words that relate to people indicates the importance of gossip in the Polari speaker’s world. As we’ve seen, the generic term for man, usually a heterosexual man, was omee (also omior homi), while a woman was a palone (sometimes pronounced to rhyme with omee as paloney, sometimes not). A gay man was named by combining the Polari words for man and woman together into omee-palone, whereas a lesbian was the reverse order—palone-omee. There’s a conflation of gender and sexuality here which from some later perspectives might be seen as problematic—to say that a gay man is literally a man-woman keys into negative stereotypes about gay men as effeminate or women trapped in men’s bodies.

This was the general thinking of the time, so it is hardly surprising that these ideas found their way into the Polari mindset. However, many Polari speakers were very camp and a good number were what people might nowadays call gender-creative. They dressed in women’s clothes—either by dragging up as female impersonators, or in a relatively more low-key way, by dyeing hair, wearing a touch of make-up or accessorizing with a colorful scarf.

These speakers enjoyed the aspects of their identity that were feminine and felt that they were being true to themselves when they expressed them—they may have looked and sounded like camp stereotypes but most of them didn’t view themselves or people like them negatively. Accordingly, queen keyed in to the imaginary world of Polari speakers as (female) royalty. If you are going to emulate a woman, why not be the most powerful woman in the country?

In 1981, a documentary called Lol: A Bona Queen of Fabularity was broadcast on BBC2. Starring London drag queen Lorri Lee, the documentary cuts between Lorri’s drag act at a hen night, hoovering her flat and reconstructions of her younger days coming out of national service and joining the Merchant Navy (with Lorri playing her younger self in flashbacks). Lorri waxed lyrical on the word queen, providing a lesson in the different sub-classifications:

Well what is a queen? Well you’ve met one, that’s the drag queen, that’s me . . . There’s also the camp queen, that everyone sees in the street . . . you know, “alright duck,” that type of queen . . . There’s what you call a black market queen. Now that’s the type of queen that an ordinary everyday person, and even me, could look at it, and you’d never suss that it was a queen in a million years, but they’re the types, I don’t really admire terribly . . . that usually sort of creep up on people and then strike, you know, sort of lull them into a false sense of security and then strike, and I think they’re the ones that usually get smacked in the face because of it.

But then . . . you’ve got your blob type queen, this a queen of no account, you know, she’s a little dumpy queen, walks around, usually follows a drag queen and sort of hangs on to every word it says, hoping a bit of the glitter’s going to fall off on her and one day she’s going to wake up like Prince Charming, suddenly turn into something different . . .

After that you’ve got . . . your cottage queens. Now a cottage queen is a queen that would get her trade from a cottage naturally . . . it means a man’s toilet. And I know queens . . . couldn’t pass a cottage dear, would have to go in, some would even take sandwiches and a flask, would spend a pleasant day.

In the Polari speaker’s world, gender was linguistically reversed—he was she and (less commonly) she became he. This practice of feminizing through language, referred to by artist and Sister of Perpetual Indulgence (Manchester branch) Jez Dolan, is referred to as “she-ing.” She-ing is one of the aspects of Polari that has survived into more recent decades, and the practice was so pervasive at a particular bar on Canal Street in Manchester’s Gay Village that a “She-box” was installed a few years ago, akin to a “Swear-box,” where patrons would have to put in a few coins if they she’d someone, with the proceeds being donated to charity.

In the Julian and Sandy sketches, she is occasionally used to refer to the (male) partner of a (butch) man. In the following exchange, from “Bona Bijou Tourettes,” the pair refer to their friend Gordon, who wears leather and rides a motorbike, bearing some of the identity markers of rough trade. Julian and Sandy discuss how Gordon had set himself up with a bar in Tangiers, although the venture has recently fallen through:

Julian: She walked out on him.

Sandy: Oh, that old American boiler.

Julian: Yes.

Sandy: Oh.

Julian: She moved on.

Sandy: Mm, Mm. I thought she would.

Mr Horne: Look, erm.

Sandy: I could tell you a thing or two there.

Mr Horne: Yes, er, now look.

Sandy: Make your hair curl. Don’t you talk to me ducky.

As there are enough clues regarding Gordon’s sexuality elsewhere in the sketches, we can interpret she as referring to a male partner.

Hypothetically, almost everything can be referred to as she, including oneself. Polari speakers would routinely call one another she—normally in an affectionate, sisterly way, although if they knew that the person being spoken to didn’t identify as a queen, there would be a more confrontational aspect to the pronoun. She effectively drags up the most masculine of men, without the need for a trip to the make-up counter at Selfridges, and it also acts as an insinuation that the man being talked about may not be as fully masculine or heterosexual as he presents himself to be.

To an extent this may have been wishful thinking—for many Polari speakers the ideal partner would be a butch man who did not identify as gay, the Great Dark Man of Quentin Crisp’s fantasies. However, there was also a more spiteful side to “she-ing”—the Polari speakers would have known that such men would have found the use of feminine pronouns on them to have been very insulting, so to use them was a way of taking them down a peg or two.

This explains the large number of feminizing terms for the police, who were rightly seen as natural enemies: Betty Bracelets, Hilda Handcuffs, Jennifer Justice, orderly daughters, Lily Law. These terms indicated that Polari speakers were able to turn a threat into a joke, with the added advantage that they could act as coded warnings—uttering “Betty Bracelets!” at the local cottage would have the effect of sending queens scattering in all directions.

The gender politics behind the feminizing pronouns are complicated. When gay men use she on themselves and their friends, are they parodying women in a way that borders on offensive? Are they simply complicit in their own oppression by adopting language and labels that are used in homophobic ways, and then using that oppressive language on their enemies, knowing it will hurt them even more?

In the Polari speaker’s world, gender was linguistically reversed—he was she and (less commonly) she became he.Am I over-thinking it? Polari speakers simultaneously reclaimed and weaponized she. We could argue that they were a product of their time, but after decades of Gay Liberation, she is still used by (some) gay men. I like to think of it as an affectionate word—and if it was used to hurt, then it was more about the drag queen’s uncanny ability to find a person’s weakness rather than saying anything about the speaker’s own politics.

Another pronoun, perhaps even more problematic from later perspectives, was it—which Lorri Lee uses three times in her discussion of queens quoted earlier. It was sometimes used to refer to a one-off anonymous sexual partner—signifying a form of objectification which can appear dismissive, even callous. Consider the following, from Kenneth Williams’s diary:

I met Harry who said Tom picked up a boy in the Piano and Harry said “It’s got a huge cock so Tom is silly, with that pile and all . . . so I thought hallo!“ It certainly gets around in Tangier.

To an extent such partners appear to be reduced to their physical body parts. As mentioned, another term for a sexual partner was trade, which had a range of slightly overlapping meanings. It could refer to a potential, past or current sexual partner, and usually indicated a temporary sexual relationship, sometimes a one-off.

Trade sometimes, but not always, indicated a masculine man who might not have identified as gay and would have been likely to have taken the “inserter” role in sex. Such men who were classed as trade did not usually speak Polari and probably would not have identified as trade or talked much about their sexuality.

Trade could also literally refer to a male prostitute, or to someone who would occasionally take money for sex but might not typically be viewed as a male prostitute—sailors on shore leave, for example, or Guardsmen who traditionally cruised parks looking for well-off men. Money might exchange hands; it might not. Sometimes the money would have been nominal, a way for the trade to establish his masculine, normally heterosexual credentials.

This was in a time when some men felt that they had to engage in elaborate excuses to justify having sex with one another. However, trade could also be a station on the way towards a more established gay identity. Gardiner notes the aphorism “today’s trade is tomorrow’s competition,” which indicates a downside to the endless hunt for new partners in a finite context.

Internalized homophobia or just plain nastiness might make the trade attack their sexual partner or demand money from them, hence the term rough trade, although this term could also refer more generally to working-class casual male partners.

Quentin Crisp, despite being a camp gay man, did not really use Polari in his autobiographies, although in the televised dramatization of The Naked Civil Servant he does refer to roughs—aggressively masculine working-class men who disguised their attraction to other men through harassment: “Some roughs are really queer and some queers are really rough.” And Lee Sutton cracks, “I’ve been feeling a little rough all day,” in his drag act.

__________________________________

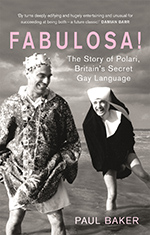

Reprinted with permission from Fabulosa!: The Story of Polari, Britain’s Secret Gay Language by Paul Baker, published by Reaktion Books Ltd. Copyright © 2019 by Paul Baker. All rights reserved.