The Fandom of the Teenage Girl Deserves More Respect

Hannah Ewens on Why Boy Band Mania Is Only Partly About the Boys

We’re in a time now where, more than ever, girls and young queer people create modern mainstream music and fan cultures with their outlooks and actions. They’re the ones at the helm of fan practices that the public have a vague awareness of: tweeting their favorite artist incessantly, writing fan fiction, religiously updating devoted social media profiles, buying “meet-and-greet” tickets and following the band around to various show dates.

This is slowly being acknowledged, in part for the money it generates for a changing music industry, and in part because of the “women in music” literature that has been published in the 2010s. It has been heartening to read all of these books, to feel as though it does matter what women have to say about their relationship to music, even if it is only legacy musicians whose stories are heard (it’s so rare that teenage-girl interests and lives are treated as though they’re of consequence). Simultaneously, I’ve watched as fans of all genders have reclaimed the somewhat derogatory label of “fangirl” online.

Of course, in its passionate exchange, fandom has never been inherently morally good—or bad. It deals in exchanges of money for goods, power struggles, privilege and intense interest or occasionally uncritical devotion towards another human being. To be a fan can be complicated, and I wanted to capture that with fairness.

My old friend E. and I had an explosive argument in our teens, a fact confirmed by coldly cutting cords on social media and a one-way return of clothes and CDs. Like most immature friendship fallouts I can’t remember the specific hurt, but the final straw would’ve been innocuous. Soon after, she left school and I’ve not seen or spoken to her since.

I reflected on our time together a lot while writing this—wondered about looking her up online and thought better of it—because there is so much to thank her for. She gave me something of a framework to understand my life, my career and my adult friendships.

About halfway through my research, I realized what it meant to be a fan. Fandom is a portmanteau of fan and kingdom—there is, as that would suggest, a king or queen regent but also a territory and community of followers. To be a fan is to scream alone together. To go on a collective journey of self-definition. It means pulling on threads of your own narrative and doing so with friends and strangers who feel like friends.

Being a fan is a serious business and this is what girls wanted to say about it.

*

Imagine screaming so hard your lung collapses. You carry on cheering somehow, using your other lung, one that has not folded, because you’re having a magical time and stubbornly choose to believe you’re just out of breath. You go to the A&E afterwards when you realize something is seriously wrong. The examining doctor discovers you are not only breathing at an extraordinary rate per minute but with a tear in the lung that is causing air to escape between the lung and the chest wall, into the chest cavity and behind the throat.

The desire of fans to create relationships for characters, fictional or real, imagined straight or queer, predates the term “slash shipping.”

Imagine that when they press on certain parts of your body it makes a sound like Rice Krispies popping. The combination of the three symptoms is something the doctor has never seen before. They consult medical records and find what you have done to yourself to be so extremely rare to occur from screaming or singing that it’s only been recorded twice in medical history: to a drill sergeant and an opera singer.

That is the story of an unnamed girl who went to a One Direction concert in 2013; her story wasn’t published in a medical journal and publicized until late 2017. “I never saw her again,” said Mack Slaughter, the doctor who treated the patient. “I told her she’d be famous and get to go on the Jimmy Fallon show and meet One Direction but she was too embarrassed.”

That same year, 2013, a documentary about 1D fans aired on Channel 4 at 10pm. This was certainly not for fans, to hold a mirror up to their fun behavior, but for parents and for viewers wanting more rowdy or licentious post-watershed material. The title sequence exploded with emotion. “It’s like a drug addiction,” says one girl. “I’ve met them 64 times,” swears another.

A voiceover dramatically declares, “They’ll stop at nothing to get close to the boys,” before cutting to a pink-haired 19-year-old from Northern England called Becky who points high up a building and says, “I was sat outside your room when you was asleep, Zayn.” These girls are Crazy About One Direction.

Viewers are introduced to one group of friends outside Manchester Arena. As they crowd around the camera, it’s evident from their colliding energies that they have a clear leader, 14-year-old leopard-print-clad Sandra. Each of them grasps at their face, clutching their phones to their aching chests as they share how much they love the boys, their words clambering over each other’s.

“I go home and cry every, every night,” says Sandra, continuing after the others have stopped. What will you do if you get to meet him today? Suddenly they all scream and stamp their feet, Sandra convulsing, and one girl with dental braces almost out of shot says, “Have an asthma attack. And cry. And die!”

Tickets for another round of 1D shows are set to go on sale. Sixteen-year-old Nadia from Dublin leans over the balcony of her block of flats, a plastic crucifix dangling. A true tableau of melancholy. “It’s just constant tears and frustration and you don’t know what to do with your life.” In the queue for tickets, she sobs. Once she has the tickets, she sobs.

After waiting hours outside Wembley Stadium for the chance to meet the boys, older girls take the failure of their mission with self-deprecating laughs. This is the lifestyle they’ve chosen, for better or for worse. For younger ones, it’s tantamount to heartbreak. The camera focuses on one girl of a group, her eyes filling with tears.

A smudged “I ❤ 1D” drawn on her sad face, and a faded red heart on each cheek, her lip wobbles. “They could’ve come by now and they’re clearly not coming.” She self-consciously scrapes her fringe behind her ears, a gesture of shame for the time and effort put into their mission and: nothing. We watch her but she can’t meet the eye of the camera or filmmaker for more than a moment.

Yet those tears are a delicate side-serving to the rage featured. One tiny girl with wide kohled eyes says nonchalantly from behind her laptop, “I’m part of a fandom that could kill you if they wanted.” A large portion of the documentary is given over to their jealousy of the boys’ girlfriends, particularly pop superstar Taylor Swift, who at the time was romantically involved with Harry Styles.

Sandra sent Swift death threats over Twitter which apparently led to Sandra’s account being blocked. Leading her down a slippery slope, a voice asks what she’d do if she saw Swift now. Sitting in a full-leopard-print room, Sandra grits her teeth and uses her hands as claws, a gesture that is as comical as it is faintly disconcerting for its aggression. “I’d stamp on her head, I’d rip all her hair out, I’d squeeze her eyeballs out, I’d step on her eyeballs.” She ends with an angelic smile. “It’d just be like that.”

Plenty of the outpourings come from bedrooms, implying that whatever we hear are the girls’ distilled thoughts, and any dramatic moments we see are relatively unprompted. One of these is “the hunt,” words that refer to the tracking down of One Direction, but it’s uncertain if they are originally those of the subjects or the production team. In one sequence, girls pace around a hotel where the band are reportedly staying and find what they believe to be their room. In another, pink-haired Becky uses her phone to document the before and after of her crossing paths with Zayn.

A large portion of the documentary is given to the often homoerotic sexual fan fiction and art that pairs Harry Styles and Louis Tomlinson as a bromance or couple—with no context or explanation that this happens across all types of media fandoms. “Slash shipping” is the very commonplace fan practice of same-sex romantic or sexual pairing as imagined by fans, more or less done officially since the start of the term’s use in the mid-1970S when the first slash ship —Kirk and Spock in Star Trek— became widely accepted.

But of course the desire of fans to create relationships for characters, fictional or real, imagined straight or queer, predates the term. Ultimately, then, the tone of the entire hour could objectively be called “hysterical.”

Hayley and her friends were filmed for the documentary but never made the final edit. She lives in Scotland and still calls herself a fangirl at twenty-two, five years on. Her social media profiles show reams of crying emojis at new songs she likes, happy birthday wishes sent to pop stars or countdowns for the days until she is seeing an artist.

She recently shared a tweet with over 44,000 retweets that reads “i’m sorry but girls who didn’t have a one direction phase probably don’t have a personality now.” When I ask why she thought she and her friends were not in the film, she says, “We just weren’t crazy enough.”

“We initially thought it’d been because there’d been too many girls but after watching it we realized we weren’t outrageous. They asked us, ‘What’s the most extreme thing you’ve done to see the boys?’ and I talked about the boys’ first tour and how I camped out for the tickets with my mum. They pushed, saying things like: ‘Is that it? What else?’ It was like they were setting us up for failure. They were trying to hook, line and sinker. We knew that was the game so we just talked about real stuff.”

“I was going through a hard time so I talked about how the boys helped me through difficult days because I’d put on their music. We talked about friendship. At 18 we were saving every penny, birthday and Christmas money for this lifestyle. I’d not do anything because I needed the extra 20 quid in the bank account in case they did a tour or something, I was really prepared. But they wanted to know if we’d stopped over at their hotel or dragged them on Twitter. Just telling the good side of things didn’t make the ‘cut.'”

After months of waiting excitedly for the final product, the documentary came out and Hayley was smoldering with shame. “When the credits rolled we thought, ‘Is that honestly how people see fans of One Direction?’ They wanted us to be crazy animals who are the reason the boys have security like they do. The girls in the documentary are supposed to look a danger to the boys when in reality they’re just people who have a passion and, OK, sometimes they do take it far, but most of the time us fans are just here to have a good time and listen to music.”

“They did pick out the worst moments and made us seem worse than what we were.”

Hayley’s friend Lauren feels similarly about events. “I remember being so angry because it portrayed all us fans to be something that we’re not, if that makes sense,” she tells me. “I remember when it came out people from my school were tweeting like, ‘Oh, I can’t believe Lauren Hutcheon’s not on this doc’ because that’s how weird they thought we were. I was angry that people at my school had seen it.”

At the time it was disappointing to see she’d been cut from something that seemed significant for the fandom, but Lauren was soon grateful for their removal. “I said to Hayley, ‘it’s a blessing in disguise.’ I don’t think I’d have been able to cope if I’d been in it. People at my school were horrible to me about it afterwards and I wasn’t even in the documentary so to think what would’ve happened to those girls…”

They did recognize and recall some of the girls who featured in the film because they were there on the day, being filmed. They, to Lauren, seemed “normal,” all friends, like her and Hayley, through One Direction, and loved 1D and that was more or less it. “I wonder whether they were made out to be weird when they were getting filmed.”

Bethany, who was also 18 at the time of shooting, did make it into the film. She remembers how she was selected from millions of Directioners. “They found most people at concerts and that as a fan is when you’re at your crazier time. If they found people on the internet it would’ve been better because not everyone can afford to go to a big pop concert but everyone can afford the internet.”

To save money to get her own home, Bethany now stays with her dad in Nottinghamshire. She’s a huge fan of Disney films now but continues to save up for the solo concerts of the 1D boys. I notice her email avatar is a “KEEP CALM AND NEVER SAY NEVER” picture, referencing Justin Bieber’s soaring R&B-inflected song.

There’s just no turning back / When your heart’s under attack. Channel your truest version of self regardless of adversity, it said. Dig deep inside for bravery and strength because at one time or another you’ll need it.

“They did pick out the worst moments and made us seem worse than what we were.” But after a pause she gives a laugh. “Honestly? I’m crazy as it is so it didn’t really make a difference to me.”

__________________________________

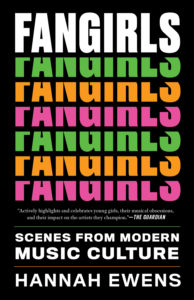

Excerpted from Fangirls: Scenes From Modern Music Culture. Used with the permission of the publisher, University of Texas Press. Copyright © 2020 by Hannah Ewens.

Hannah Ewens

Hannah Ewens is a writer and editor at VICE UK where she writes about youth culture, mental health, feminism, rock/alt pop music and film. Her first non-fiction book Fangirls: Scenes From Modern Music Culture is out now.